KIST Develops Artificial Photoreceptor and Signal Transduction Technology

Technology for creating and implanting artificial retinas for people with retinal damage caused by accidents or various eye diseases is advancing. Korean researchers have developed an artificial photoreceptor that recognizes colors just like the human eye and transmits signals.

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) announced on the 17th that a team led by Dr. Kim Jaeheon and Dr. Song Hyunseok from the Sensor Systems Research Center, along with Dr. Kim Hongnam from the Brain Convergence Technology Research Group, has produced an artificial photoreceptor with visual functions comparable to humans through ex vivo cell experiments, and developed an artificial visual circuit platform that transmits electrical signals generated by light reception in the artificial photoreceptor to other nerve cells.

For people who have lost vision due to visual impairment, macular degeneration, diabetic retinal diseases, and other retinal disorders, 'artificial retina' technology offers new hope. Artificial retina research involves inducing retinal diseases in experimental animals before applying the technology to humans, then verifying the effectiveness of the artificial retina. However, this process consumes considerable research funding and can encounter unexpected experimental variables, such as misinterpreting changes in rodent behavior caused by non-visual sensory information like smell or sound as effects of the artificial retina.

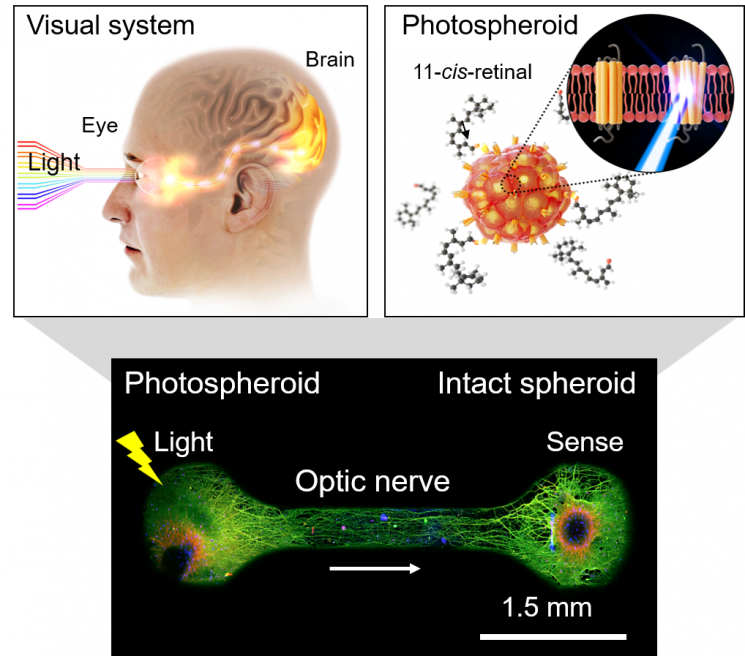

The human retina consists of cone cells and rod cells. Cone cells produce photoreceptor proteins that distinguish three colors: red, green, and blue, while rod cells produce photoreceptor proteins that distinguish brightness. The human eye sees objects through a process where light entering from outside forms an image on the retina and is transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve.

Previous artificial retina research used methods such as electroporation on single nerve cells or virus-gene injection, but there were issues where nerve cells lost function or underwent necrosis before artificially expressing photoreceptor proteins.

The research team succeeded in stably expressing artificial photoreceptor proteins by using a cell cluster called spheroid, which enhances nerve cell functionality and survival, as a platform for photoreceptor expression, thereby increasing cell-to-cell interactions. While less than 50% of nerve cells survived when photoreceptor proteins were introduced in two-dimensional cell cultures, using nerve spheroids resulted in a high survival rate of over 80%.

The team produced spheroids expressing rhodopsin (~490nm) for distinguishing brightness and blue opsin (~410nm) for color differentiation, creating spheroids with selective responsiveness to blue and green light, respectively. These spheroids reacted at the same wavelengths as colors recognized by the human eye.

Subsequently, they fabricated a device connecting a photosensitive neural spheroid mimicking the eye and a general neural spheroid mimicking the brain, successfully capturing the process of neural transmission extending to the general spheroid through fluorescence microscopy. In other words, they created a visual signal transmission model that allows exploration of how the human brain perceives signals generated in the retina as different colors.

Dr. Kim Jaeheon stated, “By verifying the visual signal transmission potential of artificial photoreceptors from multiple perspectives, this platform can reduce reliance on animal experiments and cut research costs,” adding, “We plan to produce spheroids capable of recognizing all colors visible to humans and develop them into test kits for vision-related diseases and treatments.”

The research results were published in the international journal Advanced Materials. (Paper title: Eye-mimicked neural network composed of photosensitive neural sphero)

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.