Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Branch 'Accompanying the Exploration of Chinese Anti-Japanese Independence Movement Historical Sites'

In June, the Month of Patriots and Veterans, the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch (Branch Chief Go Wook) embarked on a tour of Chinese anti-Japanese independence movement historical sites.

This tour was arranged over a 3-night, 4-day schedule (June 10?13) to visit the traces of the anti-Japanese movement remaining in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces in the Northeast Sanxing region (Jilin, Liaoning, Heilongjiang), commonly known as Manchuria, to honor and commemorate the noble spirit of the patriots.

The 26 members, with an average age over 70, departed from Incheon Airport and flew for about two hours to arrive at Harbin Airport.

Considering the inconvenience for the elderly members who endured traveling by express bus from Gwangju to Incheon Airport early in the morning, the first day’s schedule ended with visits to famous sites in Harbin such as Saint Sophia Cathedral, Stalin Park, and Zhongyang Street, where commemorative photos were taken.

The next day, the group visited Harbin Park (Zhaolin Park), mentioned in the will left by patriot Ahn Jung-geun. It is known as the place where on October 23, 1909, Ahn Jung-geun, along with Woo Deok-soon, Jo Do-seon, and Yoo Dong-ha, arrived in Harbin to plan and review the assassination of Ito Hirobumi. Walking through the leisurely park where people strolled, it was humbling to think that over 100 years ago, Ahn Jung-geun and his companions, who endured hardships across Manchuria while planning the operation, walked the same grounds with solemn and resolute hearts. Inside the park, there is a monument engraved with Ahn’s calligraphy reading ‘Cheongchodang’ and ‘Yeonji,’ and many Koreans still visit this site.

Next, the group toured the “Northeast Martyrs Memorial Hall,” which served as the Harbin Police Station of the Japanese puppet state Manchukuo from 1933 to 1945. This was the site where numerous patriots who fought against Japanese colonial rule were imprisoned, brutally tortured, and killed. After liberation, the Chinese government collected portraits and relics of the anti-Japanese martyrs and named the site the “Northeast Martyrs Memorial Hall” to preserve their legacy for future generations. According to the local guide, 32 Korean independence activists, including Park Jin-woo, Yang Rim, Li Chu-ak, Li Hong-gwan, Cha Soon-deok, and Heo Hyung-sik, are enshrined here.

Members of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch, who visited the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall inside Harbin Station, are paying their respects with a moment of silence after laying flowers.

Members of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch, who visited the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall inside Harbin Station, are paying their respects with a moment of silence after laying flowers.

The great Chinese democratic revolutionary Sun Yat-sen praised Ahn Jung-geun’s assassination of Ito Hirobumi with this eulogy upon hearing the news.

After leaving the “Northeast Martyrs Revolutionary Memorial Hall,” the group boarded a bus heading to Harbin Station as rain began to fall lightly. Anticipation grew about the emotional impact of seeing firsthand the historic site where Ahn Jung-geun struck down Ito Hirobumi, the mastermind behind the invasion of the Korean Peninsula.

The group offered a wreath in front of Ahn’s statue and observed a moment of silent tribute before touring the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall. The clock above the statue stopped at 9:30 a.m. on October 26, 1909, the time of the assassination, and through a small window, the exact spot where Ahn aimed his gun and shot Ito Hirobumi is marked on the floor. Although the memorial hall was modest in size compared to Ahn’s achievements, the fact that the Chinese government provided this space to honor a hero who was neither communist nor Chinese left a feeling of indebtedness in their hearts.

Members of the Gwangmokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch are paying their respects at the Yongjeong March 13 Anti-Japanese Martyrs' Shrine.

Members of the Gwangmokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch are paying their respects at the Yongjeong March 13 Anti-Japanese Martyrs' Shrine.

From Harbin West Station, the group took a high-speed train for four hours to Jangbaeksan Station. They stayed in Yidobaekha to view the sacred Baekdu Mountain Heaven Lake. Despite setting out early with warm coats and rain gear, poor weather forced them to forgo the ascent to Heaven Lake, instead admiring the majestic Jangbaek Waterfall to soothe their disappointment.

Departing Yidobaekha, they traveled to Myeongdong Village in Yongjeong. Along the way, they got off at an unnamed street far from residential areas and walked about five minutes along a farm road to find the “March 13 Anti-Japanese Martyrs’ Tomb,” dedicated to those who sacrificed their lives during the March 13 Manse Movement centered in Bukgando Yongjeong. Although designated as a key cultural relic by the Yongjeong City People’s Government, the site showed exposed stone walls and sparse weeds, reflecting poor maintenance. Everyone paid their respects with silent bows, their steps heavy with sorrow.

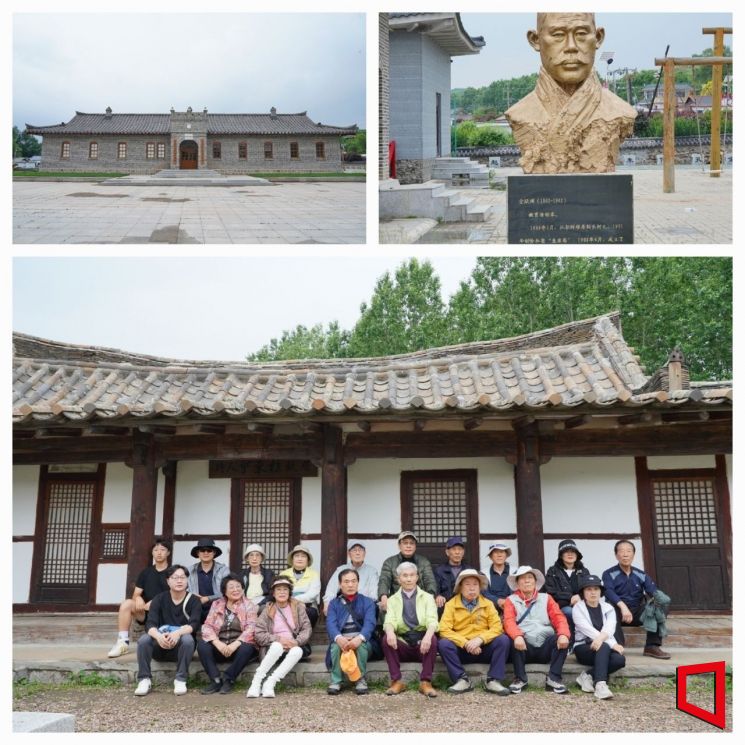

After a short distance, they arrived at Myeongdong Village, a Korean settlement established by independence activist Kim Yak-yeon, known as the “President of Gando.” Entering through a gate bearing the sign “Chinese Communist Party Myeongdong Village Branch Committee,” they found the “Myeongdong School Old Site Memorial Hall” where the school once stood, and to the right, a bust of Kim Yak-yeon. Kim was the maternal uncle of poet Yun Dong-ju. The poet’s mother, who inspired his representative poem “Seosi,” was Kim Yak-yeon’s younger sister.

From the top left of the photo, members of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch are commemoratively posing at the site of the former Myeongdong School Memorial Hall, the bust of Teacher Kim Yak-yeon, and the birthplace of poet Yun Dong-ju.

From the top left of the photo, members of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch are commemoratively posing at the site of the former Myeongdong School Memorial Hall, the bust of Teacher Kim Yak-yeon, and the birthplace of poet Yun Dong-ju.

The group entered the childhood home of poet Yun Dong-ju, who died young at 27. A somewhat incongruous large sign read “Home of Famous Chinese Korean Poet Yun Dong-ju.” Following a path engraved with the poet’s verses on stone slabs, they reached a neat tiled-roof house where Yun spent his youth. Last year, when Korea-China relations cooled, the Chinese government temporarily closed the site for internal repairs. Leaving Myeongdong Village, where peony flowers bloomed, the group pondered the Chinese authorities’ apparent intent to diminish Yun Dong-ju to merely a famous poet of a Chinese ethnic minority.

On the final night of the historical site tour, the group visited the Yanbian Autonomous Prefecture, promoted by Chinese authorities as “Little Seoul of China” and developed strategically as a tourist destination. The guide explained that with the enactment of the “Yanbian Signboard Law,” all signs are now displayed bilingually in Chinese characters and Hangul.

Despite the tight 3-night, 4-day schedule, the “Chinese Anti-Japanese Independence Historical Site Tour,” tracing the fierce and arduous footsteps of the independence movement, provided a profound lesson on the patriotic and filial attitudes we must never forget even in comfortable daily life.

All members of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch who participated in this tour are second- and third-generation descendants of independence patriots, most with white hair and advanced age. They unanimously expressed that only one direct senior heir among the descendants receives a pension, leaving many descendants still struggling, and strongly called for urgent revision of the law regarding the treatment of independence patriots.

One member, who wiped tears of joy on the day General Hong Beom-do’s remains arrived in the homeland, expressed hope that the issue of relocating General Hong’s bust would never again divide the struggles of patriots who fought for the country’s liberation far from home.

Go Wook, branch chief of the Gwangbokhoe Gwangju Metropolitan City Branch and organizer of this event, said in his closing remarks, “It was a precious time for members to see and physically feel the anti-Japanese historical sites on Chinese soil. I thank the members, most in their 70s and 80s, for safely enduring the demanding schedule together.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)