KCCI Releases Analysis Report on Breach of Trust Regulations

"Absence of Exculpation Provisions Severely Disrupts Decision-Making"

"Sentences Harsher Than Major Countries... Calls for Reform of Aggravated Penalties"

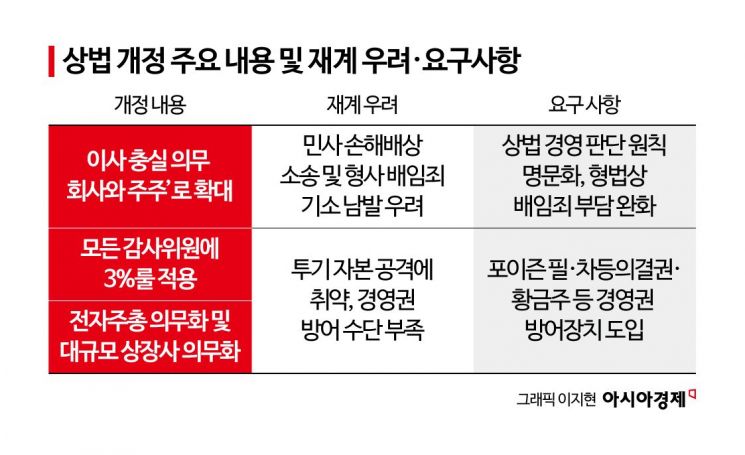

With the implementation of the amendment to the Commercial Act, which expands directors' duty of loyalty to shareholders, there have been urgent calls for institutional reforms to mitigate directors' liability for business judgment. Critics point out that the current breach of trust regime constitutes a 'Galapagos regulation' that is out of step with international standards, and that the world's highest level of criminal penalties is increasing the burden on companies.

On August 19, the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) expressed this view in its report, "Current Status and Improvement Measures for the Breach of Trust Regime." The main criticism from the business sector is that the implementation of the amended Commercial Act is causing confusion, as it is unclear whether breach of trust against shareholders can be established or whether the business judgment rule applies. The KCCI analyzed, "In the absence of an exoneration provision for reasonable business judgment, there is concern that major investment decisions and other board resolutions could be significantly hindered."

The report analyzed acquittal rates in criminal cases between 2014 and 2023, based on the Judicial Yearbook published by the National Court Administration. The average acquittal rate for charges such as breach of trust and embezzlement was found to be 6.7%, more than double the overall average acquittal rate for all crimes under the Criminal Act, which is 3.2%. This is cited as evidence that the outcome of breach of trust cases is often uncertain until the final verdict is reached.

The report identified several reasons for the high acquittal rate in breach of trust cases: the application of risk-based offenses instead of result-based offenses, the use of conditional intent, and other abstract or ambiguous legal requirements. For example, under the Criminal Act, it is unclear whether "when damage is inflicted" refers to actual damage or merely the risk of damage. However, the courts have applied breach of trust charges even when there is only a risk of loss. There have also been numerous precedents where breach of trust was recognized based on conditional intent, even without clear intent.

The breach of trust regime in Korea is structured in three layers: the Criminal Act, the Commercial Act, and the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes. In theory, corporate breach of trust cases should be governed by the special breach of trust provisions in the Commercial Act, as special laws take precedence over general laws. However, because the aggravated punishment under the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes requires a basic crime, and the special breach of trust provision in the Commercial Act is not included as a basic crime, in practice, prosecutors apply the breach of trust provision from the Criminal Act as the basic crime. This has effectively rendered the special breach of trust provision in the Commercial Act obsolete.

The KCCI first pointed out that the breach of trust provision in the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes has failed to keep pace with changes over time. The thresholds for aggravated punishment were set at 100 million won and 1 billion won when the law was enacted in 1984, and raised to 500 million won and 5 billion won in 1990. However, these thresholds have remained unchanged for 35 years. Adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), 500 million won and 5 billion won in 1990 would be equivalent to approximately 1.5 billion won and 15 billion won today.

The KCCI also raised concerns about the chilling effect on entrepreneurship caused by the excessive filing of complaints and accusations, as well as the use of criminal charges such as breach of trust to resolve what are essentially civil disputes between private parties, and called for urgent improvements in these areas.

The KCCI further noted that Korea imposes the heaviest criminal penalties for breach of trust among major countries. In the United States and the United Kingdom, there is no breach of trust crime; similar conduct is regulated under fraud statutes or resolved through civil remedies such as damages. In Germany and Japan, breach of trust is included in the Criminal Act or Commercial Act, as in Korea, but there are no aggravated punishment provisions under special laws.

According to the KCCI, Korea is the only major country that imposes aggravated punishment through the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes, resulting in exceptionally harsh sentences. If the illicit gain exceeds 500 million won, the penalty is imprisonment for at least three years, the same as for robbery or manslaughter. If the gain exceeds 5 billion won, the penalty is imprisonment for at least five years or life imprisonment, similar to murder.

The report argued that Korea should abolish both the aggravated punishment provision, which has no equivalent overseas, and the now-obsolete special breach of trust provision in the Commercial Act. If abolishing the aggravated punishment provision under the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes is not feasible, the KCCI suggested that at the very least, the monetary thresholds set 35 years ago should be updated to reflect current values. The report also emphasized the need to codify the business judgment rule, which is recognized in case law, in the Commercial Act and Criminal Act, so that directors can be exonerated from liability at the prosecution stage.

The business judgment rule holds that if a director makes a business decision based on sufficient information and with due care, the director is not considered to have breached their duty even if the company suffers losses. This principle was first established by the Delaware Supreme Court in the United States in 1988, and has since been applied through case law in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. In Korea, it was first applied in a Supreme Court case in 2004. Unlike other major countries, which mainly apply this rule in civil cases, Korea applies it in both civil and criminal cases.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.