BOK Report: "Key Issues - The Impact of Demographic Changes on Consumption Slowdown"

Consumption Slowdown Driven by Trend and Structural Factors; Structural Reforms Needed

Conditions Should Be Established for Retirees to Remain in Stable, Regular Jobs Rather Than Entering Self-Employment

An analysis has found that, due to changes in the population structure resulting from low birth rates and an aging population, the annual average rate of consumption growth is expected to slow by about 1.0 percentage point between 2025 and 2030. The rapid aging of the population caused by low birth rates and increased life expectancy, as well as population decline, are changing the demographic structure, worsening households' medium- to long-term income conditions, lowering the propensity to consume, and thereby intensifying constraints on consumption. Structural reforms have been cited as a solution to the slowdown in consumption caused by both cyclical and structural factors. The report suggests that conditions should be established so that the second baby boomer generation can work in stable, regular jobs for an extended period after retirement, rather than excessively entering self-employment.

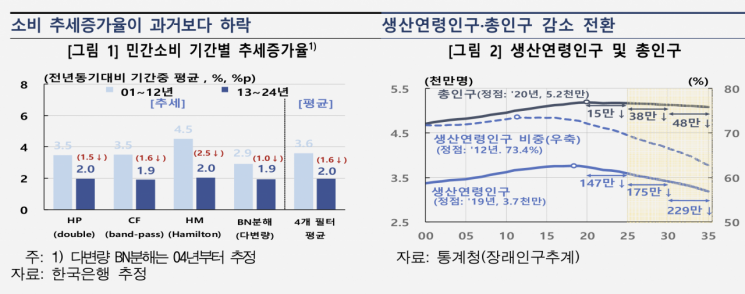

On June 1, the Economic Research Bureau and Economic Modeling Office of the Bank of Korea released a report titled "Key Issues: The Impact of Demographic Changes on Consumption Slowdown," emphasizing these points. Recent sluggishness in private consumption is attributed not only to cyclical factors but also to significant structural factors. The trend growth rate of private consumption from 2013 to 2024 dropped by 1.6 percentage points compared to the previous period (2001?2012). Park Donghyun, Deputy Head of the Structural Analysis Team at the Economic Research Bureau, pointed out, "The trend slowdown in consumption is the result of a complex interplay of various structural factors, such as the accumulation of household debt and income polarization. However, demographic changes, in particular, are having a continuous and significant impact on consumption trends through their effects on the economy's income-generating capacity, propensity to consume, and consumption composition."

The report examined the impact of demographic changes on consumption through direct channels?such as a decrease in population size (working-age population and total population) and changes in population composition (from a pyramid to an urn shape)?and indirect channels?such as the expansion of government social security spending (which can substitute for or constrain private consumption) and the spread of single-person households (mainly among vulnerable groups). As a result, population decline has constrained consumption by reducing growth potential and weakening the demand base. Park explained, "A decrease in the working-age population reduces the contribution of labor input to economic growth. As a result, potential growth declines, weakening households' income-generating capacity," adding, "A decline in total population directly limits the size of the consumer market."

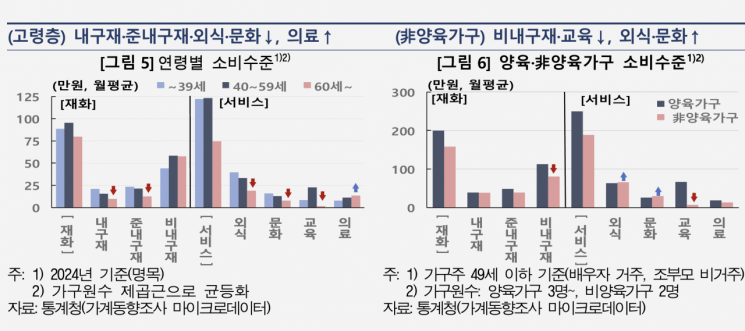

The rapid increase in the proportion of the elderly has had a negative impact on both the average propensity to consume and overall consumption capacity. As all age groups have reduced their propensity to consume due to increased precautionary savings associated with longer life expectancy, the expansion of the population aged 60 and over has caused the overall propensity to consume to fall by 6.5 percentage points over the past decade?from 76.5% in 2010?2012 to 70.0% in 2022?2024.

The consumption level of the elderly declines due to limited income and social activity after retirement, and as the proportion of the elderly in the economy rises rapidly, overall consumption capacity is weakening. In terms of consumption composition, aging in particular has been found to constrain discretionary spending on durable goods, semi-durable goods, dining out, and culture. Park stated, "Looking at consumption by age, after entering old age, consumption in most categories except for non-durable food and healthcare declines markedly," and added, "Low birth rates have had a negative impact on essential consumption items related to child-rearing, such as non-durable goods and education." On the other hand, despite smaller household sizes, non-child-rearing households have shown relatively higher spending on dining out and culture.

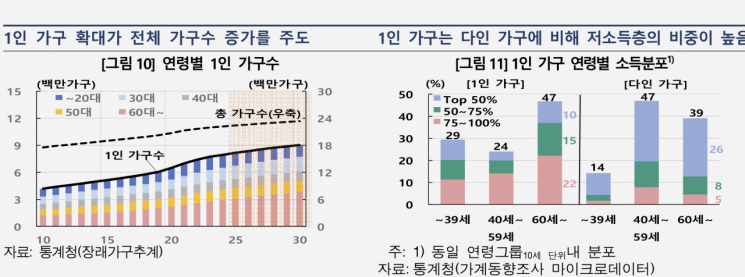

In response to low birth rates and an aging population, government social security spending is expanding, and as a result, some of the healthcare and education consumption previously borne directly by households is being replaced by government in-kind social security benefits. The increase in the number of single-person households, which has led to a rise in the total number of households, has been evaluated as quantitatively increasing overall consumption. However, since COVID-19, the inherent vulnerability of single-person households has largely offset this consumption-boosting effect.

The report estimated the direct impact of demographic changes (population size and composition) on consumption based on the private consumption identity (income × propensity to consume), dividing it into effects on households' medium- to long-term income conditions and changes in the average propensity to consume. The analysis found that demographic changes slowed the annual average rate of consumption growth by about 0.8 percentage points between 2013 and 2024. This accounts for about half of the 1.6 percentage point decline in the trend growth rate of consumption during the same period (compared to 2001?2012). Park projected, "As population decline and aging are expected to intensify further between 2025 and 2030, the impact of demographic changes on consumption slowdown?mainly through the worsening of medium- to long-term income conditions?will expand to an annual average of -1.0 percentage point."

By channel, in terms of medium- to long-term income conditions, a decrease in population size (-0.2 percentage points) and changes in population composition (0.4 percentage points) reduced labor input. As a result, with the decline in potential growth (income-generating capacity), consumption slowed by 0.6 percentage points. This is mainly because the proportion of the core working-age population in their 30s to 50s?who have relatively high employment rates, working hours, and productivity?has decreased, thereby worsening both the quantity and quality of labor input. In terms of the average propensity to consume, increased precautionary savings due to longer life expectancy (-0.1 percentage points) and changes in age distribution centered on the elderly (-0.1 percentage points) lowered the overall propensity to consume, reducing consumption by 0.2 percentage points.

Park emphasized, "While counter-cyclical policies may be effective in addressing consumption slowdowns caused by cyclical factors, structural reforms are the appropriate solution for consumption slowdowns caused by trend and structural factors." In particular, he diagnosed that creating conditions for the second baby boomer generation to work in stable, regular jobs for an extended period after retirement, rather than excessively entering self-employment, is an effective alternative. He pointed out, "By actively utilizing the human capital of the second baby boomer generation, it is possible to buffer the decline in potential growth caused by reduced labor input," and added, "Compared to excessive entry into self-employment, this can reduce uncertainty about future income, thereby helping to alleviate the contraction in the propensity to consume caused by anxiety about old age."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)