Director Jeong Jin-woo Restoring 1964 Film 'Baesin'

Um Aeng-ran and Shin Seong-il, the Film That Made Them Real-Life Lovers

"Deeper Emotions Enhance Work's Completeness, Secretly Supporting"

"When I look at an actor, I always look at their eyes first. The atmosphere that comes from their gaze completes the person and the character."

The Korean Film Archive announced on the 26th of last month that it had discovered 16 feature films from the 1960s to 1970s, including director Jeong Jin-woo's Betrayal (1964). Currently undergoing restoration, Betrayal was Jeong’s second directorial work and is known as the film where then top stars Eom Aeng-ran and Shin Seong-il developed a real-life romantic relationship. As Jeong said that he "looks at the eyes first" when casting actors, Shin Seong-il’s gaze in Betrayal is intense, and Eom Aeng-ran’s eyes carry the sorrow of an impossible love.

Director Jeong Jin-woo, who directed films such as "Betrayal (1964)," "Secret Meeting (1965)," and "Heavy Rain (1966)," is being interviewed by Asia Economy on the 29th at his office in Sinsa-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul. Photo by Jo Yong-jun jun21@

Director Jeong Jin-woo, who directed films such as "Betrayal (1964)," "Secret Meeting (1965)," and "Heavy Rain (1966)," is being interviewed by Asia Economy on the 29th at his office in Sinsa-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul. Photo by Jo Yong-jun jun21@

Meeting his early debut work after 60 years, he vividly recalled the atmosphere on set at the time. Known as the "Bulldozer of Chungmuro," Jeong, who mastered directing, acting, and producing, shared insights on Betrayal and his 60-year film career. The following is a Q&A with director Jeong.

- The film Betrayal was the first work where actors Eom Aeng-ran and Shin Seong-il felt romantic emotions toward each other. Was that atmosphere felt on set as well?

▲ No matter how talented an actor is, it’s difficult to create a good expression without genuine emotion. At the time, Shin Seong-il had just left Shin Film and was rising as a lead actor in several works, but he was often late to the Betrayal set. We had to shoot a beach scene, and when Shin Seong-il arrived late, I got angry and abruptly ordered him to jump into the water. After filming the swimming scene, the staff and I packed up and left early, and only Eom Aeng-ran remained at the site. The two of them rode together in a car, and she, a senior in the film industry, bought him dinner, so it was like a date. A few days later, I sensed a strong chemistry between them on set. Since their genuine feelings improved the film’s quality, I supported them and continued filming.

- You debuted as a film director at 23. How were you able to shoot your debut work so quickly?

▲ While attending Chung-Ang University’s law school, I was more devoted to the school theater club than studying for exams. Senior Choi Mu-ryong, who was active in Chungmuro, offered me a chance to work in film production, so I joined director Yoo Hyun-mok’s The Sadness of Heredity (1956) set. In Yoo’s next film Lost Youth (1957), I played a gangster alongside actor Kim Seung-ho, but when I saw myself on the editing screen, I looked so small and insignificant that I thought I had no presence. Actually, I dreamed of being an actor in college and often played lead roles in various works, but on screen, it just didn’t work (laughs). So I gave up acting and honed my skills as a crew member in various productions. I worked in the camera department for director Park Sang-ho’s The Rose is Sad (1958), director Shin Kyung-kyun’s Hwaseem (1958), and director Noh Pil’s If That Night Comes Again (1958), then became assistant director for Park Sang-ho’s Necklace of Memories (1959). Back then, film staff often worked unpaid to build experience, but I didn’t mind. There was always something to learn on set, and at least we got meals on time. Later, I worked under director Jeong Chang-hwa as assistant director and production manager on Horizon (1961), Jang Hee-bin (1961), and Ruler of the Land (1963), and producers kept offering me a chance to debut. I declined, wanting to learn more and mature, but producer Jeong Jin-mo, whom I knew well, earnestly proposed, so I debuted with Only Son in 1963.

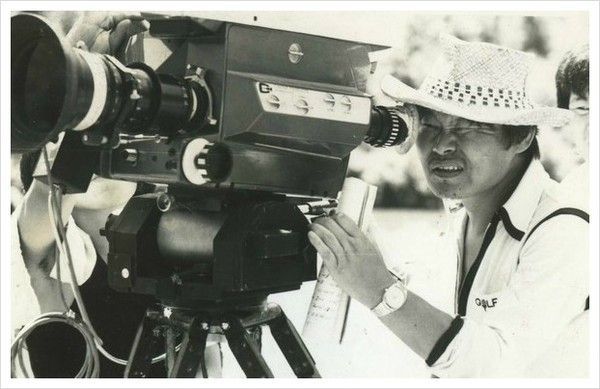

Director Jung Jin-woo, who introduced Korea's first simultaneous sound recording camera TODD-AO to the country, filming on site.

Director Jung Jin-woo, who introduced Korea's first simultaneous sound recording camera TODD-AO to the country, filming on site. [Photo by Korean Film Archive]

- The recently discovered Betrayal and later films like Chowoo and Choyeon stand out for attempting a different cinematic language compared to other films of the time. Could you elaborate?

▲ At that time, everyone in the film industry was making films like novels. Many works were based on novels, and filming was done uniformly according to the storylines. I wanted to break away from that. I resolved to make films like poetry, even if they failed. Like poetry doesn’t express everything in words, I aimed to create films that tell stories visually without dialogue. Films where the story progresses through the camera. I made “cine-poem” films, which were well received by the public, so I don’t think it was a failed choice.

- Your film Long Live the Island Frog was the first Korean film to enter the competition section at the Berlin International Film Festival. What was the atmosphere like there?

▲ I participated in the 23rd Berlin International Film Festival in 1972, where Indian director Satyajit Ray’s Thundering also competed. Back then, there weren’t many films in the competition section, so directors gathered for a press conference. At the event, criticism arose that Long Live the Island Frog had mismatched actor lip movements and dialogue due to post-dubbing. I couldn’t say anything. Even India had advanced technology for synchronous sound recording, but we were still making films with post-dubbing, despite Hollywood’s first talkie The Jazz Singer having been released nearly 50 years earlier. I wanted to prove that Korean cinema was not behind on the world stage. So I went to the UK to study synchronous sound technology and bought a TODD-AO camera in the US to shoot Yulgok and Shin Saimdang (1978). This became the first Korean film with synchronous sound recording.

A still from the film Betrayal (1964) directed by Jeong Jin-woo, recently discovered by the Korean Film Archive. The leads of this work, Shin Seong-il and Eom Aeng-ran, continued their on-screen chemistry into real life, becoming an actual couple.

A still from the film Betrayal (1964) directed by Jeong Jin-woo, recently discovered by the Korean Film Archive. The leads of this work, Shin Seong-il and Eom Aeng-ran, continued their on-screen chemistry into real life, becoming an actual couple. [Photo by Korean Film Archive]

- You were called the "Bulldozer of Chungmuro" and left many anecdotes with your fiery passion and rough speech.

▲ When I spoke harshly to actors on set, it was because I demanded performances where they fully embodied their roles for themselves and the work. It was just expressed in an angry tone, but it was my way of caring and loving the actors. If I had only been a director who yelled, how could I have worked with those actors on many projects and shared lifelong friendships?

- There was also an incident where you stormed into the Ministry of Culture and Public Information carrying gasoline.

▲ When producing Exposure (1968), which dealt with the story of a political gangster and a female reporter covering it, the Ministry repeatedly rejected the film’s censorship because it was based on the real-life political gangster Lee Jeong-jae. We changed the names and made edits, but the rejections continued. Unable to contain my anger, I went to the ministry’s second-floor office carrying gasoline, opened a container, and shouted, “I’m here to self-immolate. Everyone kneel!” protesting fiercely. Eventually, after cutting 20 minutes, the film passed censorship and became the top-grossing film in theaters that New Year. It’s a work I still feel regretful about in many ways.

- Korean cinema is gaining prestige on the global stage. How do you feel about this?

▲ Seeing director Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite win at Cannes and the Academy Awards made me feel a sense of generational change. With the advanced technical environment nowadays, directors’ works may have improved visuals, but I don’t feel the heartfelt sincerity that moves the heart. I want to see films that touch the heart even from today’s perspective.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)