[Global Focus] Why Did the Swiss Financial Legend Go Bankrupt?

First Financial Institution with Phone Banking and Internet Banking

Investment Losses and Corruption Crisis Widening

Swiss investment bank Credit Suisse (CS) has ultimately disappeared into history after 167 years. It is expected that the name CS will vanish as it is forcibly merged with its competitor, Switzerland's largest bank UBS. What happened that led to the collapse of a 167-year financial legend, which had expanded its influence worldwide, being driven to the brink of bankruptcy?

The Beginning of the Crisis... Aggressive Mergers and Acquisitions

Known as the "bank of global ultra-high-net-worth individuals," Swiss banks allowed accounts to be opened with anonymous numbers and letters while guaranteeing the highest level of security worldwide. Credit Suisse was representative of such Swiss banks. CS was the foundation of Swiss finance and was almost synonymous with the history of investment banking (IB). Established in July 1856 to finance the expansion of the Swiss railway network and industrialization, CS entered retail banking in 1905 by opening its first branch in Basel, keeping pace with the rapid growth of the middle class. It was the first among major banks to open a drive-through bank in Zurich (1962), and pioneered phone banking (1993) and internet banking (1997).

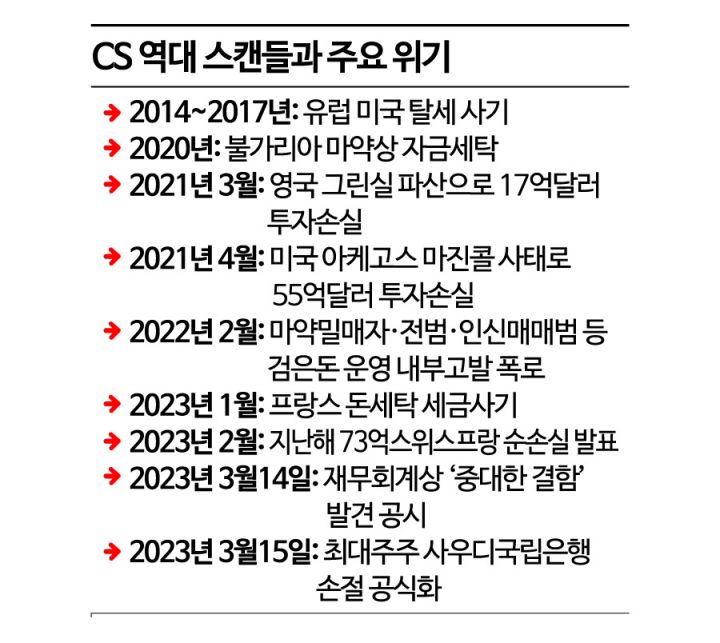

Especially in the 1990s, starting with the acquisition of First Boston, CS expanded its business through active mergers and acquisitions (M&A) such as Bank Ru and Fox Bank, transforming into an investment bank. Instead of focusing on stable businesses, CS, which had a clear risk appetite, continued to pursue an aggressive investment approach with a "high risk, high return" policy even after the 2008 financial crisis, failing to address deficiencies in risk management and internal controls.

The Spread of the Crisis... Continued Investment Losses

Then, in March and April 2021, the bank faced crises one after another with the 'UK Greensill scandal' and the 'US Archegos incident.' In early March 2021, British financial firm Greensill Capital went bankrupt, causing an investment loss of $1.7 billion. In April, CS lost $5.5 billion due to funds being trapped in the margin call incident of hedge fund Archegos Capital. While JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley minimized losses by disposing of stocks held as collateral through block deals, CS suffered the largest loss among global financial institutions due to delayed response. This dealt a direct blow to CS's creditworthiness.

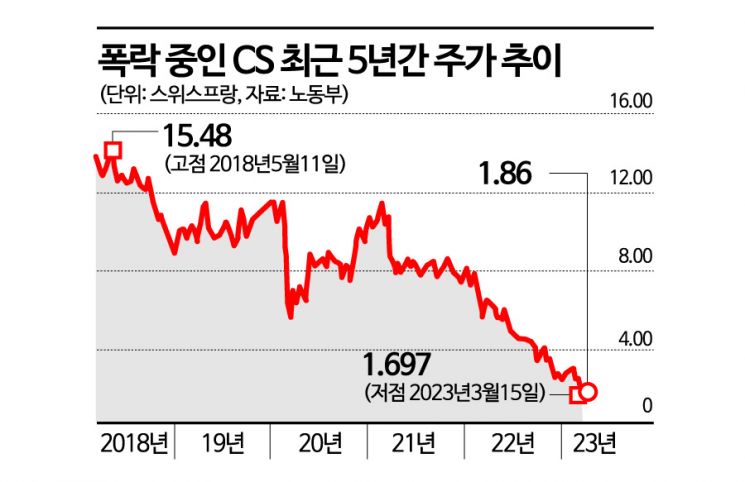

Subsequently, a series of corruption scandals including tax evasion, drug money laundering, and tax fraud surfaced, shattering the bank’s reputation built on secrecy. Management scandals led to revolving-door personnel changes, resulting in managerial chaos. A vicious cycle of declining profits and scale continued for years. As a result, over 110 billion Swiss francs (approximately 155.85 trillion KRW) of client funds were withdrawn in the fourth quarter of last year alone. The bank also recorded a record worst net loss of 7.3 billion Swiss francs (approximately 10.34 trillion KRW) for the entire year.

Amid this, news of the major shareholder's 'cutting losses' caused market panic to spiral out of control. In the recently disclosed business report, significant accounting 'material weaknesses' such as inadequate internal controls were found, amplifying financial concerns. Saudi National Bank Chairman Amar Al-Khudairi stated there would be 'no additional liquidity support plan,' triggering a wave of capital flight. Credit default swap (CDS) premiums, an indicator of CS's default risk, surged to record highs, reaching a peak of default fears.

70 Trillion Won Injected but a ‘Leaky Jar’... Drastic Measures

Fortunately, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) announced on the 16th that they would inject up to 50 billion Swiss francs (approximately 70 trillion KRW) into CS as an emergency measure to put out the fire. However, market anxiety did not subside. Amid ongoing withdrawals of customer deposits, especially by super-rich clients, pessimism spread that the authorities' 70 trillion won injection would be like "pouring water into a leaky jar."

The authorities also judged that self-rescue was impossible as credit, the foundation of the financial industry, had plummeted to rock bottom. Ultimately, they decided to sell CS to its competitor UBS. On the 19th, UBS and CS announced that they had signed a merger agreement with UBS as the surviving entity. The acquisition price was 3 billion Swiss francs (approximately 4.24 trillion KRW), with a per-share acquisition price of 0.75 Swiss francs. This was significantly below the market value based on the closing price on the 17th (1.86 Swiss francs per share).

Axel Lehmann, Chairman of the Board of Credit Suisse (left), and Colm Kelleher, Chairman of UBS, are talking with the press after a press conference held on the 19th (local time) in Bern, Switzerland.

Axel Lehmann, Chairman of the Board of Credit Suisse (left), and Colm Kelleher, Chairman of UBS, are talking with the press after a press conference held on the 19th (local time) in Bern, Switzerland. [Image source=Reuters Yonhap News]

Although the authorities called the forced merger with UBS a 'last resort,' the decision was made faster than expected. Swiss President Alain Berset explained at a press conference that "the liquidity outflows and market volatility confirmed last week (after the announcement of the authorities' liquidity support policy) showed that market confidence in CS could no longer be restored," and "this solution was UBS's acquisition of CS."

However, financial experts are skeptical about the merger synergy and the possibility of successful restructuring. This is because the business structures of UBS and CS overlap significantly, and the corporate cultures of risk-taking CS and conservative UBS do not align well. Above all, the worsening business environment and the distorted profit structure make it difficult to downsize the IB division.

The British Economist noted, "Reducing the scale of an investment bank's business is like dismantling a nuclear reactor," and "the merger of UBS and CS has weak commercial logic and will involve considerable turbulence." This was also evident in past cases such as Germany's Deutsche Bank and the UK's Royal Bank of Scotland. Once the world's second-largest investment bank after JP Morgan, Deutsche Bank entered restructuring due to a series of scandals including money laundering and interest rate manipulation, but failed to achieve results and was marginalized.

Following CS... Another ‘Weak Link’ Breaks

During this merger process, all 16 billion Swiss francs worth of contingent convertible bonds (AT1) issued by CS will be fully written off, which is expected to cause significant aftershocks. These bonds, known as 'CoCo bonds,' offer higher returns than regular bonds but carry the risk of principal and interest loss during crises. This is the first time a global major bank has forcibly written off bonds since the global financial crisis.

While the liquidity crisis faced by CS seems to be resolved with the merger with UBS, experts warn that another crisis similar to the Lehman Brothers collapse could occur centered around 'weak links' like CS. The British Economist predicted that as asset prices continue to plummet due to rising interest rates, another banking crisis could emerge anytime centered on the 'weak links' of global finance like CS. The Economist warned, "Just as the 1997 Asian financial crisis hit several countries leading to the collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), and the 2008 global financial crisis was triggered by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, financial firms driven into crisis by high interest rates and recession will mean CS is not the last."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)