Japan Introduced My Number Card in 2016

Administrative Efficiency Expected to Increase Through Information Integration

Low Issuance Rate Due to Privacy Leak Concerns

Fax and Seal Phased Out for Digital Reform

My Number Card. [Image source=Website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan]

My Number Card. [Image source=Website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan]

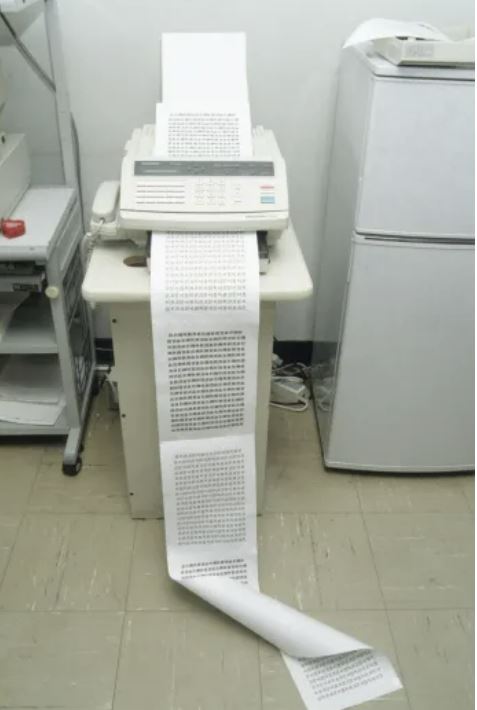

[Asia Economy Reporter Lee Ji-eun] Despite being the world's third-largest economy, Japan is often labeled a "digital laggard." Unlike South Korea, which responded swiftly to the COVID-19 outbreak, Japan's local governments compiled confirmed case numbers via fax and manual work. Administrative agencies managed information in different ways, causing major disruptions in tasks requiring personal identification, such as issuing vaccination certificates.

As administrative inefficiencies increased during disaster situations, the Japanese government introduced a measure akin to a Japanese version of the "resident registration system." The government plans to digitize information for the entire population by promoting the "My Number Card," which combines the functions of South Korea's resident registration card and public certification system. However, given Japan's culture of adhering to analog methods and public opposition, it remains to be seen whether this system can take root in Japanese society.

Personal information managed separately... Even a simple address change report is troublesome in Japan

The reason the Japanese government is focusing on introducing the My Number Card is analyzed to be due to each government office having its own distinct information management system. After the Meiji Restoration, Japan introduced the "koseki system," or family registry system, but decided to abolish it in 1948. This was because the concept of grouping families under a household head and dependents conflicted with the new constitution based on gender equality.

After abolishing the household head system, with no way to identify personal information, each government office began independently managing administration by assigning individuals codes such as the "resident code" and "basic pension number."

Because agencies used unstandardized methods, it took a long time to retrieve personal information when needed.

During administrative procedures, when information linkage between government offices was required, citizens had to submit documents multiple times, causing inconvenience. This was because administrative agencies developed information input methods without considering the need to exchange data with other agencies. In the process of sending duplicate documents, discrepancies between the two sets of information often caused even simple address change reports to become problematic.

The Japanese government expects that as the issuance rate of My Number Cards increases, administrative efficiency will be maximized in three areas: disaster response, tax payment, and social security. Each My Number Card is assigned a unique 12-digit number, and linking this number with personal information held by local governments will enable smooth information sharing among administrative agencies.

Why do Japanese citizens hesitate to get the card despite government promotion?

The problem is that despite the government encouraging card issuance since 2016, the issuance rate still has not exceeded half of the entire population. Currently, Japan's My Number Card issuance rate is 49%. Until last year, the rate was only 39%, but it rose after the government implemented a special measure offering up to 20,000 yen (approximately 190,000 won) worth of points upon card issuance.

The reasons Japanese citizens hesitate to obtain the card are concerns about personal information leakage and a cultural tendency to adhere to analog methods. The Asahi Shimbun explained that citizens "feel uneasy about the state collecting personal information, which is also a reason for the low issuance rate."

NHK also compared South Korea's resident registration system with Japan's My Number Card, pointing out the need for caution regarding state collection of personal information. NHK stated, "South Korea's rapid COVID-19 response was thanks to the resident registration number system, but even if the state uses information for good purposes, it is not necessarily right for citizens to unconditionally accept it."

However, some voices argue that an efficient personal identification system is necessary for swift response in disaster situations. In fact, the vaccination certificate application released by the Japanese government in December last year malfunctioned from the first day due to personal information identification issues. Errors occurred because local governments manually input vaccination records for about 100 million individuals into the system.

The Asahi Shimbun noted, "The My Number Card stores personal information in an IC chip, which has the advantage of unifying management of local government and hospital medical records. However, the government must properly explain to citizens the reasons for collecting this information regarding its convenience."

Japanese government aims to eliminate fax for e-government system... Citizens remain indifferent

In addition to introducing the My Number Card, the Japanese government is also striving to eliminate fax machines to digitize the administrative system. However, this effort is also facing difficulties due to negative reactions from citizens and bureaucrats.

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported that when Taro Kono, Minister for Digital Affairs, announced in August last year the plan to eliminate faxes in central government ministries, about 400 protests demanding the retention of fax machines flooded in from bureaucrats. They argued that email systems are vulnerable to security issues and that communication could be paralyzed in the event of natural disasters, recommending that backup fax machines be kept.

NHK analyzed, "As Japan enters a super-aged society, the number of elderly people who find it difficult to use smartphones is increasing, solidifying a culture of relying on fax machines, which will be hard to disappear."

Additionally, in June last year, while serving as Minister for Administrative Reform in the Suga Yoshihide Cabinet, Minister Kono pushed to abolish the mandatory stamping (inkan) requirement when preparing documents.

However, due to opposition from groups adhering to analog culture, Minister Kono's "de-stamping" policy lost momentum. Stakeholders in the 170 billion yen stamp industry protested. Moreover, even when companies implemented remote work, employees still came to the office to stamp documents, showing that the culture of valuing stamps has not easily disappeared in the public sector.

The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) pointed out Japan's efforts to break away from analog culture, stating, "Until early 2020, fax machines, face-to-face meetings, and paper contracts with seals were standard in Japanese offices," and added, "Japan may be the most tradition-bound high-tech country in the world."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)