Council of Judges, an Advisory Body, Effectively Granted Decision-Making Power

Random Assignment Principle in Question; Mandatory Disclosure of Minority Opinions Also Controversial

First Instance Verdict Scheduled for January 16; Yoon's Appeal o

The "Establishment of a Special Court for Insurrection Cases Act," which passed the National Assembly on December 23, is structured so that the decision to establish, compose, and operate the special court is entirely entrusted to the Seoul High Court. Neither the Ministry of Justice, the National Court Administration, the Constitutional Court, nor any separate recommendation committee is involved. The system is designed so that no specific institution can intervene in the composition of the court, thereby maintaining the appearance of separation of powers and judicial independence. On the surface, the approach of "let the High Court handle it" blocks potential constitutional issues.

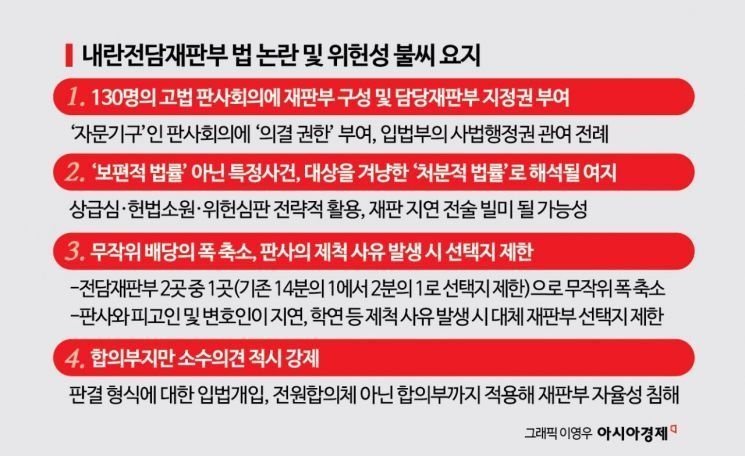

The problem lies in the details. The bill stipulates that a council of about 130 high court judges will form two special panels dedicated to insurrection cases and designate which panel will handle each case. This gives what is essentially a consultative body the authority to make binding decisions, now enshrined in law. Although the High Court already operates special panels for cases such as sexual violence, elections, corruption, and rental fraud under internal regulations, this bill makes such arrangements mandatory by law.

The most contentious issue is the principle of random assignment. Even if the council of 130 judges establishes a rule for random assignment, the fact that only two special panels are legally mandated raises questions about the true randomness of the process. The original random assignment system created by the National Court Administration, which involved a 1-in-14 chance, is fundamentally different from a 1-in-2 random assignment.

In reality, given the nature of insurrection cases, it is expected that a significant number of high court judges may have grounds for disqualification due to connections with defendants or defense attorneys. In such cases, even if a reason for disqualification arises, it may become virtually impossible for judges to recuse themselves. For example, if a judge on the panel is a law school classmate, from the same hometown, or a high school alumnus of the defendant or their attorney, questions of fairness may arise. Similar concerns could also emerge if a judge has a history of involvement in organizations with specific leanings, such as the International Human Rights Law Research Society or the Our Law Research Society. With limited options for panel selection, it becomes difficult to change the panel when such issues are raised.

In these circumstances, defendants will have more grounds to argue that their right to a fair trial has been violated. One senior high court judge stated, "Although the process is formally random, the different pool sizes mean that, in practice, it could become a structure where recusal is impossible." Such procedural differences could provide defendants with an opportunity to strategically use constitutional complaints or requests for constitutional review as delay tactics. Another senior judge commented, "It could be argued that this is not a universal law, but a 'dispositional law' targeting specific cases or individuals."

Another point of controversy is that the bill requires minority opinions to be explicitly stated in the written judgments for both first and second instance panel decisions. It is unusual to mandate the disclosure of minority opinions in individual panel decisions rather than only in Supreme Court en banc rulings. Traditionally, the format of judgments and the disclosure of minority opinions have been left to the discretion and autonomy of the judiciary, so mandating this by law is seen as legislative intervention in the form and content of judgments. There are also concerns that excessive exposure of the internal deliberations of the panel could undermine the neutrality and stability of trials.

Legal experts believe that if the special court is established, appeals involving obstruction of official duties-such as the case of former President Yoon Suk-yeol allegedly interfering with the arrest by the Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials-will likely be among the first to be assigned. The first trial for this case is scheduled for sentencing on January 16 next year, following the final arguments on December 26.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)