"A System That Embraces Failure Is the Foundation of Science...

Korea Must Shift to a Long-Term Structure"

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to three scientists who developed a new molecular structure known as "Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)." Among them, Professor Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University, Japan (age 74), was named a co-recipient, making Japan a double Nobel Prize winner this year, following the Physiology or Medicine Prize just two days earlier.

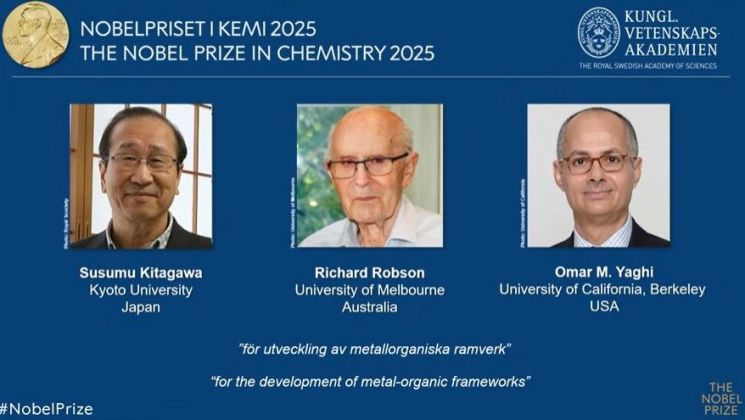

This year's Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to three individuals: Professor Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University, Japan (from the left), Professor Richard Robson of the University of Melbourne, Australia, and Professor Omar M. Yaghi of the University of California, Berkeley, USA. Provided by Yonhap News Agency

This year's Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to three individuals: Professor Susumu Kitagawa of Kyoto University, Japan (from the left), Professor Richard Robson of the University of Melbourne, Australia, and Professor Omar M. Yaghi of the University of California, Berkeley, USA. Provided by Yonhap News Agency

At a press conference on October 8 (local time), the Nobel Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced, "The three laureates demonstrated that combining metals and organic molecules can create a completely new dimension of 'space' in chemistry."

Heiner Linke, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, described Metal-Organic Frameworks as "materials with enormous potential." Another committee member, Olof Ramstr?m, likened MOFs to "Hermione's bag from Harry Potter," saying they are materials capable of holding an unimaginably large amount within a small space.

MOFs are porous structures created by linking metal ions with organic molecules. They contain countless microscopic pores invisible to the naked eye, through which various molecules can pass or be stored. Thanks to this property, MOFs have the potential to address a wide range of environmental and energy challenges facing humanity, such as carbon dioxide capture, hydrogen storage, atmospheric moisture absorption, and drug delivery.

This year's award officially recognizes the longstanding achievements of three scientists: Richard Robson, who proposed the diamond-like structure concept in 1989; Susumu Kitagawa, who realized a porous structure capable of gas adsorption in 1997; and Omar Yaghi, who completed the highly stable MOF-5 in the early 2000s.

With Professor Kitagawa's Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Japan has already achieved double victories in the scientific fields this year, following the Physiology or Medicine Prize. Among the three winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine announced on October 6 was Simon Sakaguchi, a distinguished professor at Osaka University in Japan. Professor Kitagawa expressed his feelings to reporters gathered at the award announcement press conference via telephone, saying, "It is a great honor and joy to have my long-standing research recognized."

"A System That Embraces Failure Creates Nobel Laureates"

Domestic researchers emphasize that this achievement goes beyond scientific results, highlighting that differences in research environments and systems played a crucial role.

Kim Jaheon, a professor at Soongsil University who collaborated with Professor Omar Yaghi, said at a briefing held at the Korean Federation of Science and Technology Societies (KOFST) conference room on October 8 after the Nobel Committee's announcement, "Professor Yaghi attached significance even to minor data, recording failures as part of the research process," adding, "Such perseverance was possible within a system that allows researchers to endure failure."

He noted, "Japan has established a structure over nearly 100 years that allows researchers to develop a single topic through long-term trial and error," and pointed out, "In a system like Korea's, which is focused on short-term achievements, such research is difficult." Professor Kim further emphasized, "Creative and challenging research carries a high risk of failure. However, Japan has a system that embraces such failures," adding, "If Korea wants to win a Nobel Prize, it must shift its support to focus on potential rather than success rates."

This year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine co-recipients, American biologists Mary Bruncko and Fred Ramsdell, and Japan's Simon Sakaguchi (from left). Photo by Yonhap News

This year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine co-recipients, American biologists Mary Bruncko and Fred Ramsdell, and Japan's Simon Sakaguchi (from left). Photo by Yonhap News

He also said, "In Korea, project cycles are short, and policies change every ten years, forcing researchers to constantly change their topics." He concluded, "In such a structure, it is difficult to accumulate research."

Professor Kim stated, "While it is not possible to provide unlimited support for reckless research, there needs to be institutional flexibility to support research that is meaningful even if it has only a 1% chance of success," adding, "The Nobel Prize does not come overnight. There must be a structure that can withstand the test of time." He reiterated, "The level of Korean researchers is already world-class," and stressed, "Now, research funding must move away from evaluation-centered approaches and allow for long-term investment."

Japan's '100-Year Research,' Korea's '10-Year Disconnection'

Since the early 20th century, Japan has established a long-term research support system focused on basic science. The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, provides individual researchers with stable funding and space so they can focus on a single topic for over 20 years. Even if there are setbacks along the way, the evaluation cycles are long, and researchers' positions and livelihoods are not threatened.

In contrast, most of Korea's government research and development (R&D) projects are structured around short-term achievements. The number of papers and patents becomes the main evaluation criterion, and when a project ends, so does the funding. When policy directions shift, research topics also change like trends, making it difficult to accumulate research over time.

Experts commonly agree that, in light of this year's Nobel Prize, Korea must also transition to "science policies that can withstand the test of time." Joo Sanghoon, a professor in the Department of Chemistry at Seoul National University, said, "Research on new conceptual materials like MOFs inevitably involves trial and error," lamenting, "With three-year project cycles, it is difficult to continue such research." He added, "We need to recalibrate the balance between basic and industrial research."

Professor Kim stated, "Korea also has sufficient potential. The key is to create systems that can withstand the test of time and institutional challenges." He continued, "Nobel Prizes do not come from just publishing good papers. They come from policies that support promising research to the end," adding, "If a system that endures failure is established, Korea can certainly achieve similar results."

The government is also aware of these structural limitations. Since this year, the Ministry of Science and ICT has been developing "mid- to long-term basic research enhancement plans" and is working to improve the research funding structure that currently focuses on short-term achievements. A Ministry official stated, "To address the limitations of projects that currently end in three to five years, we are reviewing a long-term basic research project model that can last more than ten years," adding, "Stable support for basic research will become the foundation of future industries."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.