Professor Jinho Yoon, Department of Environmental Energy Engineering, GIST, and Jina Park, PhD student.

Professor Jinho Yoon, Department of Environmental Energy Engineering, GIST, and Jina Park, PhD student.

A research team has announced findings showing that not only the rise in temperature due to climate change, but also the phenomenon of fine particles (aerosols) in the air reflecting sunlight and cooling the Earth's surface, can actually increase relative humidity. The researchers warned that this could intensify heat stress experienced by people.

The Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST) stated on July 10 that the research team led by Professor Jinho Yoon from the Department of Environmental Energy Engineering, in collaboration with domestic and international researchers, has identified that surface cooling caused by aerosols is a major factor behind the increase in relative humidity.

Aerosols refer to fine solid or liquid particles suspended in the atmosphere, which can originate from both natural sources (such as volcanic eruptions, wind-blown dust, sea salt particles) and anthropogenic sources (such as fossil fuel combustion, industrial activities, vehicle emissions). These particles reflect or absorb sunlight in the atmosphere, altering the surface temperature, and also influence cloud formation, resulting in complex effects on the climate system.

The research team conducted a detailed analysis of changes in relative humidity and their causes over approximately 60 years (1961-2020) using high-resolution atmospheric reanalysis data (ECMWF Reanalysis v5, ERA5) provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, as well as large-scale climate model simulations.

As a result, the team identified the "aerosol-humidity mechanism," whereby fine aerosol particles emitted from factories or vehicles scatter sunlight, cooling the Earth's surface. This leads to reduced evaporation, stagnation of water vapor, and ultimately an increase in relative humidity.

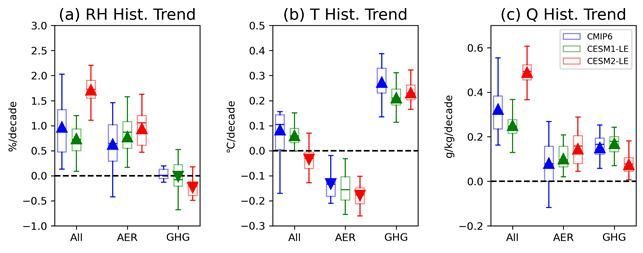

Comparison of the Effects of Greenhouse Gases and Aerosols on Relative Humidity (RH), Temperature (T), and Specific Humidity (Q).

Comparison of the Effects of Greenhouse Gases and Aerosols on Relative Humidity (RH), Temperature (T), and Specific Humidity (Q).

This mechanism demonstrates that a certain level of aerosols increases relative humidity and acts as a "buffer" that suppresses temperature rise. However, if aerosol emissions are rapidly reduced, this cooling effect disappears, causing temperatures to rise quickly. As a result, heat stress indices that combine temperature and humidity (such as discomfort and danger indices) can increase sharply, introducing new climate risks to human health and society as a whole.

These results reveal the paradox that "clean air does not necessarily guarantee a safe climate." In fact, in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP) region, which spans northern India, Bangladesh, and eastern Pakistan, relative humidity (RH) has shown a marked increase over recent decades.

This region is one of the most densely populated in the world, home to about 1.4 billion people. During the hot and humid summer season, threats such as heat stress, reduced agricultural productivity, and the spread of infectious diseases are extremely high. When high temperatures are accompanied by high relative humidity, evaporation of sweat is hindered, making thermoregulation difficult and posing direct risks to vulnerable groups such as the elderly and children.

The research team confirmed, using multiple satellite and observation datasets along with the CESM2-LE model, that relative humidity in the IGP region increased by an average of about 10.3% from 1961 to 2020. The analysis showed that approximately 95% of the increase in relative humidity was due to a rise in atmospheric water vapor, while the decrease in temperature also contributed (5%) but had a relatively minor effect.

Aerosols with strong scattering effects (such as sulfates and organic carbon) were found to drive a series of processes: cooling the surface, stabilizing the atmosphere, promoting water vapor accumulation, and ultimately increasing relative humidity. The research team also conducted single forcing experiments to separately identify the effects of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and aerosols. The results showed that GHGs raise surface temperature and decrease relative humidity, while aerosols lower surface temperature and increase relative humidity, exhibiting opposite effects.

For example, when only greenhouse gases were changed, water vapor increased, but relative humidity tended to decrease due to the rise in temperature. In contrast, when only aerosols were changed, surface temperature dropped and relative humidity increased.

Through analysis of various future climate scenarios, the research team projected that relative humidity may reach a peak at some point and then begin to decline.

Professor Jinho Yoon stated, "If we overlook the duality that greenhouse gases and aerosols influence the climate in completely opposite ways, 'clean air' could actually increase short-term risks of heatwaves and humidity." He added, "In high-risk, densely populated regions like the IGP, the way we harmonize greenhouse gas reduction and aerosol mitigation policies will significantly shape the climate risks humanity will face."

Jina Park, the first author of this study and a PhD student, said, "High humidity hinders sweat evaporation and thermoregulation, and explosively increases heat stress indicators such as wet-bulb temperature." She added, "This study demonstrates that air quality improvement and carbon neutrality policies must be established from an integrated perspective."

This research was led by Professor Jinho Yoon and PhD student Jina Park from the Department of Environmental Energy Engineering at GIST, with participation from Professor Hyungjun Kim of KAIST, Professor Jihoon Jung of Sejong University, Dr. Sooyeon Moon of the APEC Climate Center, and numerous international researchers. It was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea's Mid-Career Researcher Program, the Recruitment Program of Foreign Outstanding Scientists, and the Korea Meteorological Administration's climate change response research project.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.