Restoring the Core Texts of Korean-Japanese Ancient History Inscriptions Distorted by Historical Manipulation

Interpreting the Gwanggaeto the Great Stele in Korean Word Order

Why Change the Distorted Landscape of Ancient Korean, Chinese, and Japanese History? A 'Masterpiece' That Could Be a Game Changer Tackling the Difficult Issues of East Asian and Korean Ancient History Has Emerged.

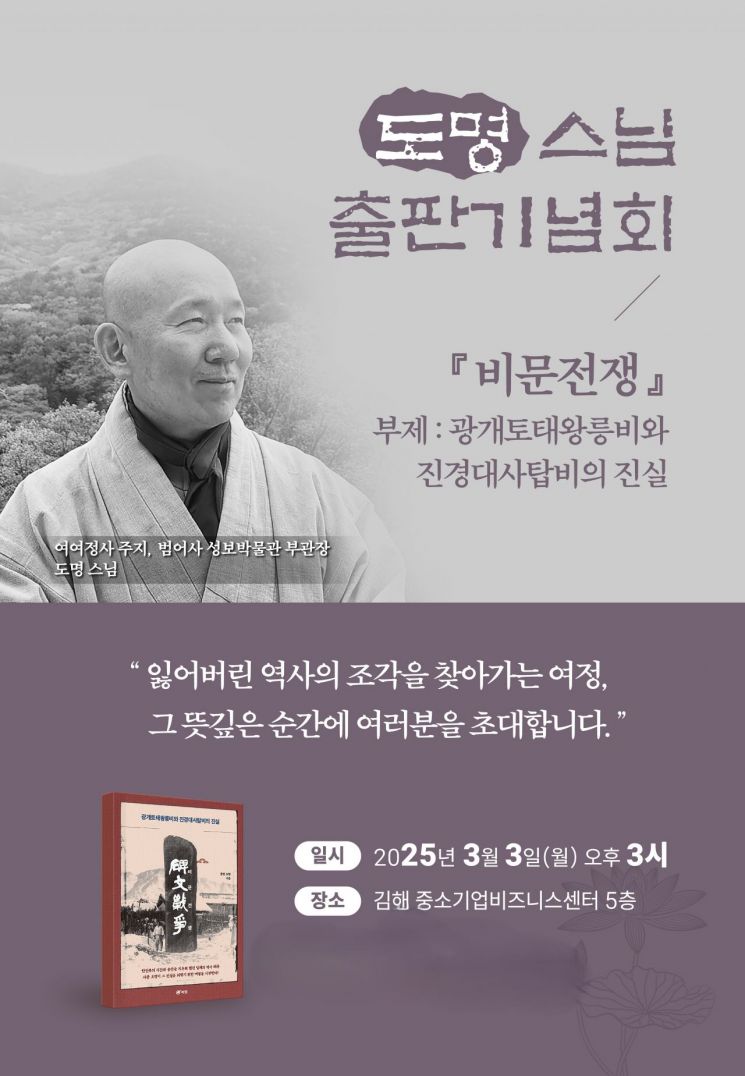

Domyeong Monk (Deputy Director of the Beomeosa Temple Cultural Heritage Museum) is publishing a new history book. He is well known as the author of "Opening the Lock of Gaya Buddhism," a book dealing with Queen Heo Hwang-ok’s honeymoon journey from India in AD 48 and the introduction of Buddhism to Korea.

Domyeong, who has studied for years the Gwanggaeto the Great Stele?one of the greatest mysteries of ancient Korean history?and the Jingyeong Daesa Pagoda Stele, which has long been misused as a tool for distorting Korean-Japanese history, has resolved these issues from a new perspective different from existing views.

While exploring the early history of Gaya through Gaya Buddhism, he questioned the prevailing academic consensus, which was influenced by the Japanese colonial-era theory that Gaya was part of Imna (the Imna theory). He focused on two of the three main evidences for Imna on the Korean Peninsula: the Gwanggaeto the Great Stele and the Jingyeong Daesa Pagoda Stele.

Just as a Seon (Zen) master in Buddhism devotes himself wholeheartedly to breaking through the koan (hwadu, 話頭), the gateway to enlightenment, the author immersed himself in solving this problem for years, sometimes forgetting even to eat. Inspired by the fact that the Japanese colonial government sent spies ahead to study and manipulate the history of target countries before territorial invasions, he meticulously examined the two steles, uncovering many issues and beginning his research.

The author first thoroughly analyzed the results of previous researchers, identifying contradictions, and based on this, produced meaningful new findings. Regarding the Gwanggaeto the Great Stele, he intensely investigated, like a detective chasing a criminal, the Japanese Imperial General Staff’s motives and methods for altering the stele’s inscriptions, specifically the distortions of the 'Sinmyo year record' and the 'Gyeongja year record.' As a result, he restored the original characters that the Japanese had altered or deleted and argued for a logical and reasonable interpretation fitting the historical context, attracting attention from citizen historians and many interested parties.

Interpreting the stele in Korean word order was a fresh attempt differing from previous approaches. Additionally, clarifying several controversial characters was another achievement in stele research. Beyond the stele alterations, he also addressed major issues such as the king’s name (wangmyeong, 王名) of Gwanggaeto the Great and the naming of the stele itself. Furthermore, the author’s claim about the king’s 'Japanese archipelago conquest theory' suggests significant possibilities beyond mere entertainment.

His detailed study of rubbings also challenges the common belief that the original rubbings were unaltered, asserting that even these were pre-altered by the Japanese, which is expected to cause a stir in academic circles. Therefore, he argues that the original rubbings do not exist; if they do, they are likely copies of the Sagawa’s Ssanggu Gamuk rubbing, which the author believes the Japanese had already hidden deeply somewhere at that time.

Moreover, the author sees the cause of Gaya’s decline not as the southern campaign (namjeong, 南征) of Gwanggaeto the Great, as existing academia claims, but as the southern campaign of Jangsu Wang. He views Gaya, which maintained a neutral stance, being caught in the crossfire of war and migrating en masse to the Japanese archipelago as one of the causes. He also regards the prevailing academic theory of Gwanggaeto’s southern campaign as a historical fabrication by Japanese official historians to solidify the Imna Japanese Headquarters theory.

Regarding the term ‘北阻海’ (Bukjohae) in the 'Sungshin 65 Year Record,' the character ‘阻’ (jo) is commonly understood to mean ‘blocked,’ but the author is the first in domestic and international historical academia to suggest, based on six usages of ‘阻’ in the Nihon Shoki, that it may mean ‘rough’ or ‘rugged’ rather than ‘blocked.’

The author also states that the Jingyeong Daesa Pagoda Stele, one of the evidences confirming the Imna Japanese Headquarters on the Korean Peninsula, became a victim of historical distortion because the Japanese twisted the interpretation of its inscription. He claims that the Japanese altered the reading and changed nouns into verbs or adjectives, completely transforming the content of the inscription. Therefore, he overturns the existing theory that General Kim Yushin, the hero of the unification of the Three Kingdoms, was an ancestor of Daesa Jingyeong, asserting instead that Kim Yushin was recorded on the stele due to his valuable connection in accepting the surrender of Daesa’s ancestor, Chobalseongji.

Author Domyeong insists that history should be viewed from the perspective of ‘the truth as it is’ (jeonggyeon, 正見). By removing the delusion of Japanese historical distortion and looking at the two steles ‘as they are,’ we can recover the lost ancient Korean history and properly restore the diminished pride of the Korean people.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![From Bar Hostess to Organ Seller to High Society... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Counterfeit" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)