Countries Experiencing Rapid Economic Changes Face Generational and Gender Conflicts

Clash Between Traditional Male Values and Modern Female Perspectives

Countries with Moderate Fertility Rates Spend More Time Modernizing, Resulting in Fewer Conflicts

"Need for Changing Perceptions That Men and Women Should Perform Equal Roles at Home and in Society"

Claudia Goldin, a Harvard University professor and the 2023 Nobel Prize winner in Economics, argued that Korea's ultra-low birthrate stems from rapid economic changes during the industrialization period. Countries like Korea and Japan, which experienced rapid economic growth, faced conflicts between traditional values and modern demands, with men and women holding different views on childbirth, leading to today's ultra-low birthrate phenomenon.

Last month, Professor Goldin released a working paper titled "Babies and Macroeconomy" at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), presenting research findings on why countries with ultra-low birthrates, such as Korea, have seen a sharp decline in fertility rates.

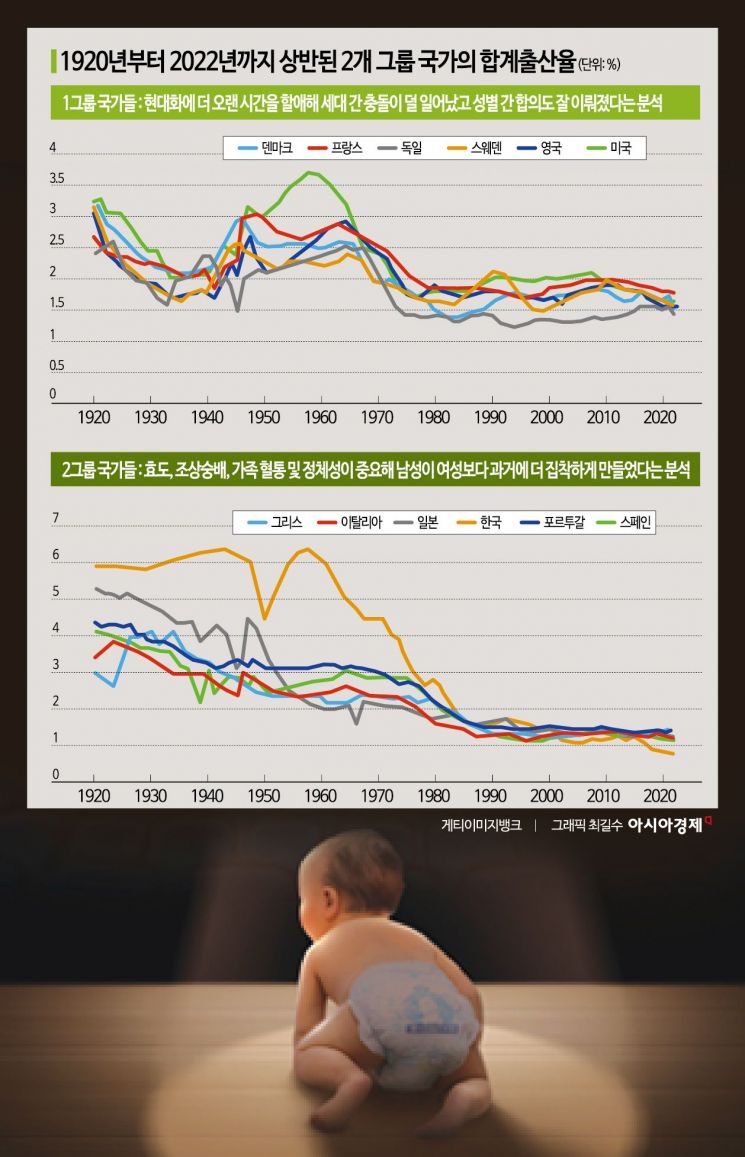

The report divided countries into two groups based on fertility rates. The first group includes Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States, which started with moderate fertility rates since the 1950s and have maintained moderate fertility rates. The second group includes Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Portugal, and Spain, which began with high fertility rates but have since experienced ultra-low fertility rates.

Countries Experiencing 'Rapid Economic Change' Face Ultra-Low Birthrates...Mass Migration to Cities While Retaining Traditional Family Values

The study found significant differences in economic growth between these groups during the 1960s and 1970s. Countries in the first group saw continuous growth in per capita GDP from 1920 to 2022. In contrast, countries in the second group experienced stagnation between 1920 and 1930, did not recover until the 1950s and 1960s, and then underwent rapid economic growth after the 1960s. These countries quickly embraced modernization waves, but citizens' beliefs, values, and traditions changed slowly.

During this process, countries in the second group experienced large-scale population migration from rural areas to cities. In 1960, the average rural population ratio was 29% for the first group countries and 50% for the second group countries; by 2023, these ratios had decreased to 16% and 21%, respectively. This decline in rural population ratios occurred in all countries except Portugal until the early 2000s.

Professor Goldin emphasized that migration is very important in fertility rate changes. People migrating from rural to urban areas bring traditional beliefs and practices with them. Among the migrants' children, daughters benefit more from modernization, while sons gain more from maintaining the past through inheritance or family businesses. Therefore, men in rapidly modernized countries tend to hold on to traditional beliefs and perform much less housework and caregiving labor compared to men in countries with sustained growth, she analyzed.

In fact, as of 2019, the gender gap in housework and caregiving hours was 3.1 hours in Japan and 3 hours in Italy, whereas it was only 0.8 hours and 0.9 hours in Sweden and Denmark, respectively. At that time, the total fertility rates were 1.36 in Japan, 1.27 in Italy, and 1.7 in both Sweden and Denmark. The larger the gender gap in housework and caregiving time, the lower the total fertility rate.

Men's Traditional Values vs. Women's Modern Values Clash...Leading to Differing Views on Childbirth

Professor Goldin cited Korea as the most extreme example among the second group countries. Assuming a boy was born in Korea around 1980, his parents would have been born in the turbulent late 1950s, and his grandparents would have spent their childhood in the 1930s. At that time, the economy did not change rapidly, so the living standards of the parents and grandparents were not very different. However, the boy's parents grew up during the 1960s when incomes rose sharply, with actual income at marriage increasing fourfold, and many people migrating en masse from rural areas to Seoul. In this process, the parents brought traditional values to the city, and the son grew up with the perception that he should marry within a traditional Korean family, where the husband is dominant and the wife is responsible for housework and child-rearing under a patriarchal system.

However, Professor Goldin argued that if there was a daughter born in the 1980s, the situation would be different. Around 2005, when she married, per capita income had increased 4.5 times compared to her birth, and the proportion of women aged 25-35 with a college education rose from 24% in 1995 to 51% in 2005. The employment rate of women aged 25-29 also increased from 48% to 68% during the same period. While sons still retained many of their parents' traditional values, women gained greater autonomy in modern society, leading to a clash of values between the two genders, which manifested as ultra-low birthrates.

Especially in countries like Korea and Japan, which emphasize filial piety, ancestor worship, and family lineage, men tend to cling more to the past than women, while women benefit more from modernization, the analysis showed.

Professor Goldin viewed this phenomenon as leading to differences in men's and women's views on childbirth. During periods of rapid economic and social change, men may desire more children than women. This is because women tend to spend more time with children, and if they want more children, they risk sacrificing their careers or becoming economically vulnerable due to lower income.

At the end of the report, Professor Goldin explained, "Rapid economic change challenges deeply held beliefs from the past, and beliefs change more slowly than technology or economic changes. This can cause conflicts between generations and genders and lead to a sharp decline in fertility rates."

She emphasized the need for social awareness changes so that men and women perform equal roles at home and in society to solve the low birthrate problem. She said, "If there is trust that fathers and husbands can provide time and resources (for housework and childcare), the differences in fertility desires between genders can disappear. Trust can be ensured in countries or states where there is social condemnation of men not providing financial, temporal, and emotional resources to the family." She explained that the high employment rates of women and high fertility rates in most Nordic countries stem from such differences.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.