Over 1,000 Missing Adults Found Dead Annually

More Than 900 Cases Unresolved

'Missing Persons Act' Stalled in National Assembly... Facing Possible Repeal

On the 29th of last month, twin brothers in their 20s were found dead by a river in Gimhae-si, Gyeongnam. Their family reported them missing two days later after losing contact following their departure without their mobile phones on the 25th, four days before they were found. The police, noting that they left their phones behind, judged it was not a simple runaway case and launched a search, but by the time they were found, the brothers were already deceased.

Last year, over 50,000 adult runaway reports were filed with the police, with more than 1,000 individuals found dead. However, due to legal and institutional shortcomings regarding adult disappearances, the police have been unable to conduct active investigations. Since the 'golden time' for missing person cases is generally recognized as 24 hours, there are calls for establishing systems that enable prompt police investigations.

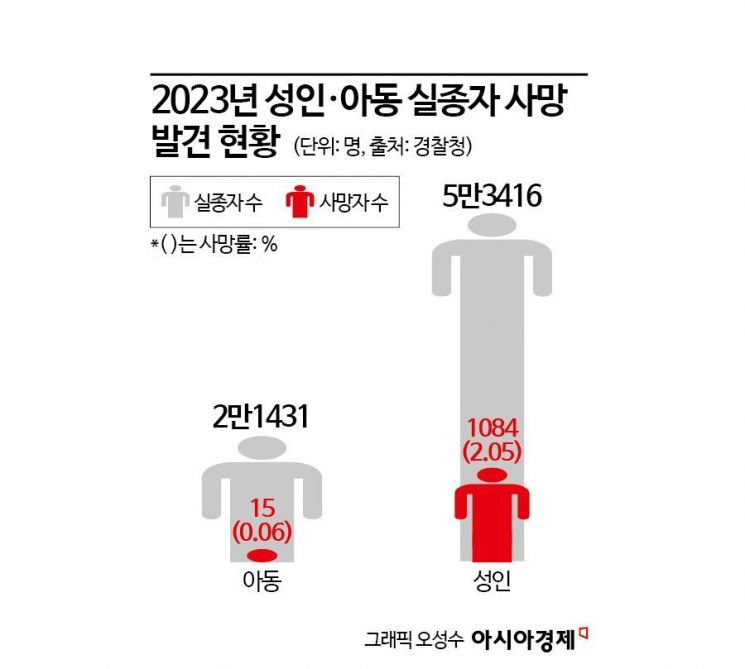

According to statistics from the National Police Agency on the 13th, 53,416 missing person reports for adults aged 18 and over were filed last year. Among them, 1,084 (2.05%) were found deceased. This means that on average, three adult missing persons are found dead every day.

The number of adults found dead after going missing was 1,696 in 2019, 1,710 in 2020, 1,445 in 2021, and 1,200 in 2022. Over five years, about 2.8% (7,134) of the total 253,768 reported missing persons were found dead. In contrast, for children, 120,120 missing reports were filed over the past five years, with only 0.07% (87) found deceased.

The disproportionately high number of deaths among missing adults is attributed to lukewarm initial investigations. Under current law, for children under 18, persons with disabilities, and dementia patients, the police can immediately conduct active searches such as location tracking and card usage analysis upon a missing report, even without suspicion of crime or suicide.

However, for adults, even if a missing report is filed, they are classified as runaways, and unless a criminal suspicion is identified, the police find it difficult to immediately initiate a search. A police official explained, "For missing children, there is a legal basis under the Missing Children Act that allows mobile phone location tracking. However, for missing adults, there is no legal basis, so investigations rely on CCTV and inquiries, limiting search methods."

Delays in initial investigations cause the golden time to be missed, turning cases into long-term disappearances. According to the National Police Agency, the number of unresolved missing cases under ongoing police investigation was 721 in 2023, a 2.4-fold increase compared to 295 cases in 2019.

Consequently, there is a growing demand for the enactment of a 'Missing Persons Act' for adults to enable prompt investigations, but the bill is currently pending in the National Assembly. Two bills aimed at establishing grounds for searching for missing adults were proposed in the 21st National Assembly, but both failed to pass the Administrative Safety Committee and are likely to be discarded due to the expiration of the assembly's term. There are concerns that the law could be misused to find individuals hiding from debts or other obligations, and that it might infringe on adults' right to self-determination.

Professor Lee Geonsu of the Department of Police Science at Baekseok University pointed out, "The golden time for missing person cases is 24 hours. If the missing person is not found within a day, the probability of finding them rapidly decreases." He added, "In countries like the United States and Australia, when a missing person case occurs, the risk level is assessed based on seven criteria including the duration of disappearance and suspicion of abduction, and investigations begin accordingly. We should also establish our own risk assessment criteria so that the police can decide whether to investigate, which would prevent misuse of the law. Therefore, the law must be enacted even if it requires supplementation."

Professor Kim Youngsik of the Department of Police Administration at Seowon University said, "Currently, the threshold for police to start investigations is high, as a criminal suspicion must be confirmed. There is a need for alternatives to lower the threshold for investigation, even at the directive level, so that if families provide sufficient evidence such as medical insurance records, the police can initiate preliminary investigations."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)