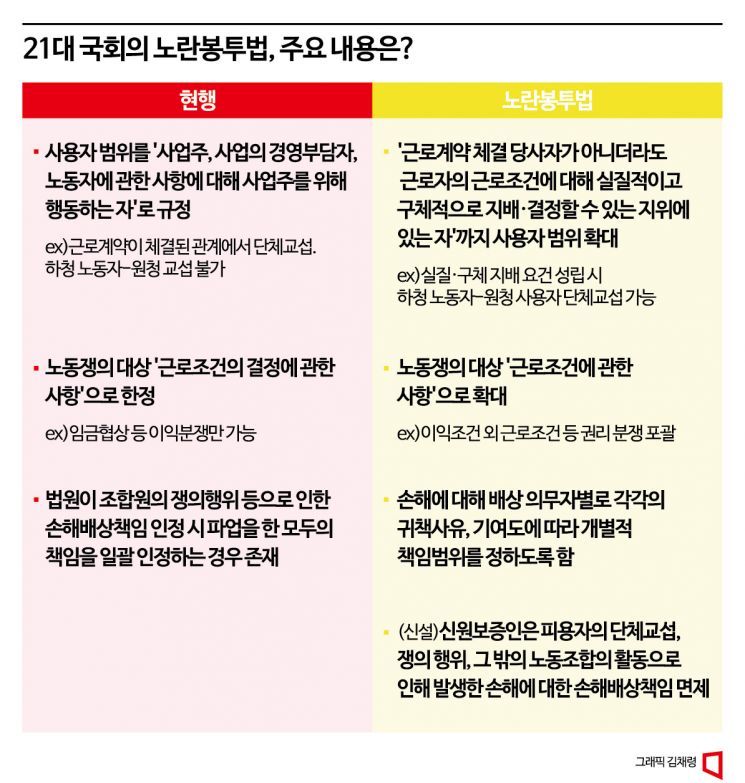

The amendment to the Labor Union Act, known as the ‘Yellow Envelope Act,’ introduced provisions limiting the liability of labor unions for damages. Among the three key elements contained in the Yellow Envelope Act?▲expansion of the concept of employer ▲expansion of the concept of labor disputes ▲limitation of the union’s liability for damages?the limitation of the union’s liability is the most crucial and a major point of contention between labor and business sectors.

Under the current Labor Union Act, unions or union members cannot be held liable for production disruptions caused by lawful strikes, but there are no separate provisions regarding claims for damages arising from illegal strikes. Therefore, the general civil law provision on joint tortfeasors applies, allowing employers to hold not only the unions participating in illegal strikes but also individual union members fully liable for damages. Although internal reimbursement among union members can be settled afterward depending on the degree of responsibility, individual union members must initially bear full responsibility as joint tortfeasors for the entire damage.

However, the Yellow Envelope Act newly stipulates that when a court recognizes liability for damages caused by labor disputes, i.e., when the illegality of the strike and the occurrence of damages are acknowledged, “the scope of responsibility must be individually determined for each liable party according to their degree of fault and contribution.” Since the provisions of the Yellow Envelope Act have not yet been promulgated or enforced, there is no precedent, and clear interpretative standards have not been established. Therefore, it is possible to interpret this provision in two ways: whether it imposes the burden of proof on the employer from the outset of establishing liability for damages, or whether it merely regulates the employer’s burden of proof concerning limitation of liability (limitation of damages) based on contribution, which is already recognized through precedent. However, considering the legislative background that the opposition party introduced the bill in response to labor demands and the reasons for the amendment, the prevailing view interprets it as requiring the employer to prove the fault of each union member and claim damages corresponding to that fault from the stage of filing a damage claim.

Joint Tortfeasors under Civil Law Are Liable as Indivisible Debtors... Full Damage Claims Possible Against Each

Article 3 of the current Labor Union Act (Limitation on Claims for Damages) stipulates that “an employer cannot claim damages from a labor union or workers for damages caused by collective bargaining or labor disputes under this Act,” thereby limiting claims for damages against unions or union members even if the employer suffers damage during lawful labor disputes.

Since the Labor Union Act does not separately regulate claims for damages arising from illegal labor disputes, Article 760 of the Civil Act (Liability of Joint Tortfeasors) applies. Paragraph 1 of Article 760 states that “when multiple persons jointly commit a tort causing damage to another, they shall be jointly liable for the damage,” and Paragraph 2 provides that “even when it is impossible to determine which of the multiple persons’ acts caused the damage, the same applies.” Paragraph 3 of the same article states that “instigators or accomplices are regarded as joint actors.”

Although the provision uses the term “jointly,” the Supreme Court interprets the relationship between joint tortfeasors and the victim as a ‘quasi-joint obligation’ relationship, which has a stronger effect on securing claims than general joint obligations. In other words, each joint tortfeasor is liable for the entire damage. Unlike joint obligations with a ‘subjective joint relationship’ among debtors, in quasi-joint obligations, reasons such as debt forgiveness between specific debtors do not affect the other debtors.

For example, if ten people collectively assault a victim resulting in the victim’s death, the victim’s bereaved family can claim damages and consolation money for the death from each of the ten joint perpetrators without needing to determine whose assault directly caused the death. Assuming the total compensation is 1 billion KRW, if one perpetrator pays 100 million KRW, the remaining debt of the other nine perpetrators reduces to 900 million KRW. However, if the bereaved family forgives the debt of one perpetrator, the debts of the remaining perpetrators do not disappear and remain intact.

Although quasi-joint obligations do not recognize internal responsibility shares due to the absence of a subjective joint relationship, the Supreme Court acknowledges subrogation relationships based on each party’s degree of fault in joint torts. For instance, if a perpetrator who should be responsible for about 50 million KRW due to a lower degree of fault pays 100 million KRW to the bereaved family, they can recover the excess 50 million KRW from other perpetrators with greater responsibility through subrogation.

Applying this to claims for damages related to illegal strikes, if an employer suffers 1 billion KRW in damages due to an illegal workplace occupation by a union, the employer can claim the entire 1 billion KRW from the union and union members. However, unlike general joint tort cases where the Supreme Court does not consider individual responsibility ratios, it exceptionally recognizes limitation of damages based on responsibility ratios among the union, union leaders, and simple strike participants, citing the principle of equity. The difference with the Yellow Envelope Act is that such limitation of union members’ liability is left to the court’s judgment based on comprehensive circumstances during the trial, and the employer is not required to prove each union member’s contribution individually.

Son Kyung-sik, Chairman of the Korea Employers Federation, held a press conference with economic organization officials at the Press Center in Jung-gu, Seoul, on the 13th, announcing a "Joint Statement Condemning the Deterioration of the Labor Union Act and Proposing the Exercise of Veto Power." From the second left: Woo Tae-hee, Vice Chairman of the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry; Choi Jin-sik, Chairman of the Federation of Medium-sized Enterprises; Chairman Son; Kim Ki-moon, Chairman of the Korea Federation of Small and Medium Business; Kim Chang-beom, Executive Vice Chairman of the Korea Economic Association; and Kim Go-hyun, Executive Director of the Korea International Trade Association. Photo by Kang Jin-hyung aymsdream@

Son Kyung-sik, Chairman of the Korea Employers Federation, held a press conference with economic organization officials at the Press Center in Jung-gu, Seoul, on the 13th, announcing a "Joint Statement Condemning the Deterioration of the Labor Union Act and Proposing the Exercise of Veto Power." From the second left: Woo Tae-hee, Vice Chairman of the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry; Choi Jin-sik, Chairman of the Federation of Medium-sized Enterprises; Chairman Son; Kim Ki-moon, Chairman of the Korea Federation of Small and Medium Business; Kim Chang-beom, Executive Vice Chairman of the Korea Economic Association; and Kim Go-hyun, Executive Director of the Korea International Trade Association. Photo by Kang Jin-hyung aymsdream@

Employers Must Prove Fault and Contribution of Each Liable Party... Business Sector Says “Practically Impossible”

However, the Yellow Envelope Act places the existing content of Article 3 of the Labor Union Act into Article 3, Paragraph 1, and newly establishes Paragraph 2 limiting the union’s liability for damages and Paragraph 3 excluding the liability of guarantors.

Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Yellow Envelope Act states, “When a court recognizes liability for damages caused by collective bargaining, labor disputes, or other activities of labor unions, it shall individually determine the scope of responsibility for each liable party according to their degree of fault and contribution.”

The reasons for the amendment state, “Regarding labor disputes, courts currently impose the entire amount of damages on each joint tortfeasor, including labor unions and union members, without specifically calculating the scope of each party’s liability. Considering that the right to collective bargaining is a constitutional right, it is necessary to prevent excessive liability being imposed on each actor as is currently the case. Therefore, when courts recognize liability for damages caused by labor disputes by union members, they shall individually determine the scope of responsibility for each liable party according to their degree of fault and contribution.”

The labor sector argues that claims for damages against individual union members are a major obstacle to workers’ collective action rights, as employers use them as a weapon to induce union withdrawal. For example, in the Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering case, hundreds of billions of KRW in damages were claimed against a small number of union members, and there have been cases where workers under heavy damage claims and provisional seizures took extreme measures.

On the other hand, the business sector argues that claims for damages are almost the only means to respond to illegal strikes, and if the amendment is enforced, this means will be effectively nullified, causing the employer to bear the full damage from illegal strikes. It is practically impossible for employers outside the union to prove the contribution or responsibility of individual union members participating in illegal strikes, and if the employer cannot concretely prove the fault and contribution of each liable party, courts will have no choice but to dismiss the claim, making damage claims difficult.

Another problem is that the amendment denies joint liability only for union activities, which contradicts the principle of civil law and the Supreme Court’s stance that multiple debtors bear joint liability for collective illegal acts with unclear individual responsibility. While the special nature of labor relations should be considered to prevent the constitutional right to collective action from being suppressed by damage claims, this applies only to lawful labor disputes. Granting special privileges for illegal acts by unions ultimately protects the perpetrators and is unfair.

Meanwhile, Article 3, Paragraph 3 of the Yellow Envelope Act states, “Notwithstanding Article 6 of the Guarantor Act, guarantors shall not be liable for damages arising from collective bargaining, labor disputes, or other activities of labor unions.”

The reasons for the amendment state, “Employers can claim damages from third-party guarantors for damages caused by labor disputes, and the guarantor system actually acts as a means to suppress union activities. Therefore, guarantors are exempted from liability for damages caused by labor disputes.”

Article 1 of the Yellow Envelope Act’s supplementary provisions sets the enforcement date as “the day six months after promulgation,” and Article 2 (Application of Limitation on Damages) stipulates that “the amended provisions of Article 3, Paragraphs 2 and 3 apply only to damages arising from collective bargaining, labor disputes, or other union activities after the enforcement of this Act.” Unlike the expanded definitions of employer and labor disputes (Article 2), the provisions limiting damages do not apply retroactively but only to cases after the enforcement date.

On June 29, in front of the Supreme Court in Seocho-dong, Seoul, union members hold related hand placards at the Metalworkers' Union press conference following the Supreme Court ruling on damages for the Hyundai Motor illegal dispatch irregular workers' strike.

On June 29, in front of the Supreme Court in Seocho-dong, Seoul, union members hold related hand placards at the Metalworkers' Union press conference following the Supreme Court ruling on damages for the Hyundai Motor illegal dispatch irregular workers' strike.

Supreme Court Recognized Exceptional Limitation of Liability in Hyundai Motor Strike Case Last June

In June, the Supreme Court overturned and remanded the appellate court’s ruling that recognized 50% liability of union members in a damages claim filed by Hyundai Motor Company against workers participating in a strike by the Metal Workers’ Union Hyundai Motor Irregular Workers Branch. The Supreme Court stated, “Viewing the scope of liability for damages of the labor union, which decided and led the illegal labor dispute, and individual union members as the same may suppress the constitutionally guaranteed rights of workers to organize and collective action, and contradicts the principle of equitable and reasonable distribution of damages. Therefore, the degree of limitation of liability for individual union members should be judged comprehensively considering their position and role in the union, the circumstances and extent of participation in the labor dispute, contribution to the damage, actual wage level, and the amount claimed.”

Immediately after the ruling, the labor sector evaluated it as “a ruling with essentially the same intent as the Yellow Envelope Act.” The Federation of Korean Trade Unions stated, “This is an important ruling sounding the alarm against indiscriminate damage claims by employers for labor disputes, confirming the legitimacy of the Yellow Envelope Act currently pending in the National Assembly.”

However, it is difficult to view the ruling as one that fundamentally limits the liability of individual union members participating in strikes as the Yellow Envelope Act does.

The Supreme Court explained the ruling’s intent, stating, “Although the principle is not to individually assess the degree of liability for damages borne by joint tortfeasors, the Supreme Court has recognized that in certain cases, the limitation of liability ratios among joint tortfeasors can differ exceptionally based on the principle of equity. This ruling is an extension of such precedents, stating for the first time that in cases where a manufacturer claims damages for fixed costs due to production stoppage caused by illegal labor disputes involving individual union members, the degree of limitation of liability for individual union members should be judged comprehensively considering their position and role, circumstances and extent of participation, and contribution to the damage.”

In fact, the Supreme Court ruled in 2006 that “union members who participate in illegal labor disputes following the union’s decision and leadership cannot be expected to disobey the union’s instructions once the dispute policy is decided by majority vote. It is practically difficult to expect union members to individually judge the legitimacy of the labor dispute during urgent situations, and requiring such judgment may weaken workers’ rights to organize.”

In other words, the ruling clarified that it is difficult to expect individual union members to disobey union instructions and that requiring them to judge the legitimacy of labor disputes in urgent situations may suppress constitutional rights. Considering the special nature of labor disputes, the court can exceptionally assess the degree of limitation of liability individually for each union member. However, this does not mean that union members’ liability is always limited, nor does it mean that employers must assess the degree of fault of each union member from the outset of damage claims as the Yellow Envelope Act requires.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor also stated in a press release immediately after the ruling, “The ruling presents the legal principle that individual union members can have a lower liability ratio than the union as a collective. It is unrelated to Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Labor Union Act amendment, which recognizes a special exception to quasi-joint liability only for illegal acts of labor unions and requires individual calculation of damages for each tortfeasor.”

Rather, the Supreme Court ruling can be seen as confirming that under the current legal system, union leaders who lead illegal strikes and simple participants can bear damage liability according to their degree of responsibility through court judgment during trials.

Minister of Employment and Labor Lee Jeong-sik is announcing the government's position on the passage of the Yellow Envelope Act at the Government Seoul Office Building on the 9th. The Yellow Envelope Act was passed in the National Assembly plenary session held that afternoon through the opposition parties' unilateral processing.

Minister of Employment and Labor Lee Jeong-sik is announcing the government's position on the passage of the Yellow Envelope Act at the Government Seoul Office Building on the 9th. The Yellow Envelope Act was passed in the National Assembly plenary session held that afternoon through the opposition parties' unilateral processing.

Issue with Significant Impact on National Economy... Requires Public Consensus

The government, ruling party, opposition, labor, and business sectors show stark differences in views regarding the enforcement of the Yellow Envelope Act. The opposition and labor sectors, which proposed the bill, argue that the passed amendment (committee alternative) reflects only the minimum necessary content to substantially guarantee the right to collective bargaining and urge its prompt promulgation. Meanwhile, the government, ruling party, and business sectors warn that it will lead to widespread strikes, causing great confusion and disputes in industrial sites, and call for President Yoon Suk-yeol to exercise his veto power.

However, it is clear that the Yellow Envelope Act has aspects inconsistent with the current legal system and that despite its significant impact on the national economy, it is questionable whether there is sufficient public consensus on the necessity of its introduction.

Im Dong-chae, a labor law specialist and partner at the law firm I&S, said, “The so-called Yellow Envelope Act imposes collective bargaining obligations on employers who are not parties to the employment contract and expands labor disputes to cover rights disputes that could previously be resolved through judicial remedies. If the law is enforced, there is concern that strikes will become more frequent.”

Im also pointed out, “Unlike existing Supreme Court precedents holding labor unions and union leaders jointly liable for all damages caused to employers by illegal labor disputes, the Act individualizes liability, potentially limiting damage liability. This is a significant and radical change to established legal principles and Supreme Court precedents, which may threaten legal stability. Such a drastic change requires sufficient public consensus beforehand and meticulous legal discussions within the National Assembly.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.