#. Gu Mo, former CEO of an e-commerce company, was indicted on charges of making employees work over 52 hours per week. A second-year employee who worked 64 hours and 20 minutes over 5 days from November 24, 2014, ended his own life on December 3 of the same year. During the trial, CEO Gu claimed, "Despite the department head's objections, the employee voluntarily worked overtime."

On the 6th, the government announced a 'working hours system reform plan' allowing up to 69 hours of work per week. In response to opposition from opposition parties and labor groups, the government explained, "It is not that one works 69 hours every week," as employees can take 'concentrated rest' through long vacations, etc.

The government’s stance through the reform plan is that it can actually reduce 'unpaid labor.' Under the current system, 'employers avoid punishment' by often recording only 52 hours worked even if employees actually work more, using such 'tricks.'

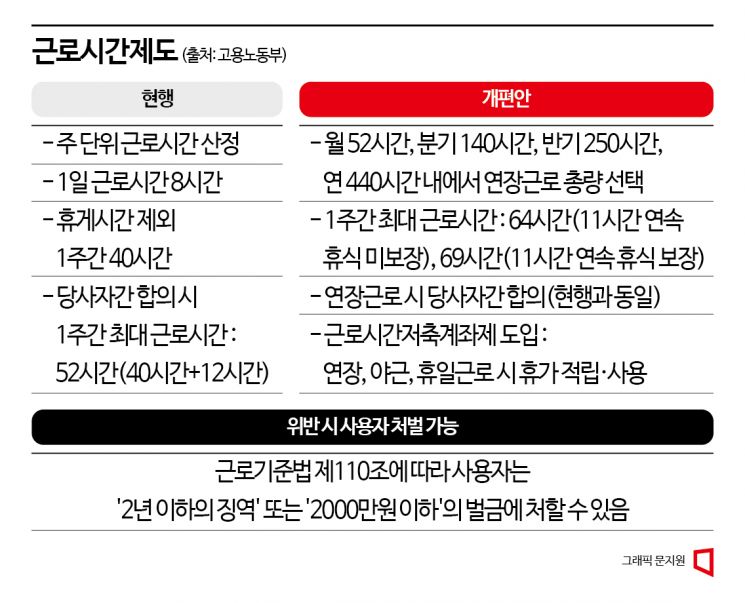

How has criminal punishment for violations of working hours been carried out so far? The current Labor Standards Act, revised in 2018, stipulates that employers who violate the 52-hour workweek can face imprisonment of up to 2 years or fines up to 20 million won.

Weekly working hours cannot exceed 40 hours excluding break times. With mutual agreement, working hours can be extended up to 12 hours per week (total 52 hours).

According to the Supreme Court interpretation, 'working hours' refer to the time when employees provide contracted labor under the employer’s direction and supervision, while 'break time' means time freed from the employer’s direction and supervision, which employees can use freely. Time during which free use of break time is not guaranteed and employees are effectively under the employer’s direction and supervision is included in working hours.

In the case of Kwak Mo, former CEO of Korail Networks, indicted for making shuttle bus drivers work over 52 hours per week, the first trial court acquitted him, judging that although drivers worked 18.53 hours a day, about 7 hours were waiting time, so the 52-hour weekly limit was not exceeded. However, the second trial court convicted him, reasoning that waiting time was not genuine break time due to activities like meals, restroom use, refueling, and car washing.

The Supreme Court acquitted him. It stated, "There was no evidence that the company or CEO interfered with or supervised the use of waiting time, and it appears the drivers could freely use it as rest time." It emphasized that whether the employer effectively directed and supervised waiting time should be examined on a case-by-case basis.

In criminal trials, most cases where employers were found guilty of related charges resulted in fines. In CEO Gu’s case, both the first and second trials found him guilty but imposed fines of 4 million won each. The first trial court noted, "The value of achieving work-life balance through appropriate working hour regulation is institutionalized by the Labor Standards Act," and "This case requires punishment as a warning against the practice of employers naturally demanding overwork from employees." However, it considered that the incident occurred before the 2018 revision of the Labor Standards Act, which strengthened employer penalties.

Even in cases applying the current Labor Standards Act, sentences did not differ significantly. A representative of an automobile parts manufacturer in Gyeongbuk was tried for making 219 employees work 17 hours of overtime per week from January to October 2021, exceeding the 12-hour limit. Several employees worked '73 hours per week.' The first trial court sentenced him to a fine of 5 million won, stating, "There are circumstances worthy of consideration, and many employees petitioned for leniency."

Meanwhile, the government plans to submit amendments to the Labor Standards Act and related laws to the National Assembly in June or July after a 40-day legislative notice period ending on the 17th of next month.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)