[Aftermath of Forced Labor Solution]

South Korea Waiting Only for Japan's Response

The Core of Historical Perception Differences

"Even while being beaten by hunger, I licked the white-thorn flowers that bloomed white."

This is the title of a testimony collection of forced mobilization victims published in 2021. It was taken from an oral account by forced labor victim Kwon Chang-yeol, who was taken to Japan as a laborer in 1941 and recounted his experiences. Approximately 7 million people were recruited for forced labor from 1939 to 1945, including Kwon. They were transferred to coal mines, railroads, and civil engineering sites, and many died from beatings, torture, accidents, malnutrition, and drowning.

The record titled "70 Years History of Japan Transportation Corporation" reported as follows: "Laborers transported from Busan to Shimonoseki numbered about 500 to 1,000 daily, divided by industry such as coal mines, mines, railroads, and civil engineering, and further divided by region including Kyushu, Shikoku, Kanto, Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and South Pacific islands for transportation and placement. This started in June of Showa 16 (1941)."

Though described plainly, it reveals the tragic reality of forced mobilization sites where people were 'transported' like slaves at the time.

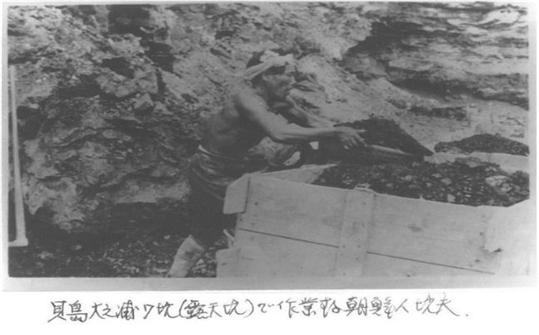

Joseon miner working at Gaijima Onoura 7 Mine (Open Pit) (Material released by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety National Archives in 2019)

Joseon miner working at Gaijima Onoura 7 Mine (Open Pit) (Material released by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety National Archives in 2019)

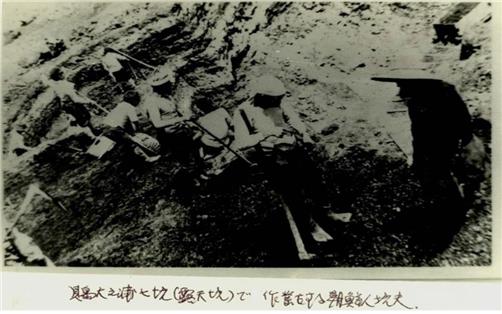

Korean miners working at Gaijima Onoura 7 Mine (open-pit mine) (Materials released by the National Archives of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety in 2019)

Korean miners working at Gaijima Onoura 7 Mine (open-pit mine) (Materials released by the National Archives of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety in 2019)

1990s Reconciliation and Compensation... Carried Out Without Recognizing the 'Illegality' of Colonial Rule

Although forced labor, which was inhumane and violated human rights, was not widely known, there were attempts by Japanese companies for reconciliation and compensation. In September 1997, Nippon Steel paid 2 million yen per person as consolation money to the families of forced mobilization victims. The war crime company Fujikoshi also compensated about 30 million yen to female labor corps victims in July 2000 and reached reconciliation.

In 1999, Japan Steel Pipe delivered consolation money of 4.1 million yen to victims who had filed lawsuits over forced labor at the Kawasaki factory after eight years. Regarding Chinese forced mobilization, there were also measures such as compensation, apology, and memorial ceremonies following lawsuits filed against Kishima Construction in 1989. At that time, the Tokyo High Court recommended in an addendum that "the problems of the perpetrator companies should not be left unattended, and reconciliation and consolation of victims in any form should be pursued."

Experts point out that in the 1990s, compensation by war crime companies for forced labor was possible because the Japanese government did not take a leading role, and the 'illegality' of colonial rule was not recognized; thus, compensation was made at the level of moral responsibility. The issue was treated as a civil matter between companies and individuals, and companies viewed the matter from a 'humanitarian' rather than 'nationalistic' perspective.

The atmosphere changed in the 2000s when lawsuits expanded to U.S. courts, especially after the Korean Supreme Court explicitly recognized the 'illegality' of colonial rule in its 2018 ruling. The Japanese government began to intervene seriously. The argument that "it was completely and finally resolved by the Korea-Japan Claims Agreement" also emerged at this time.

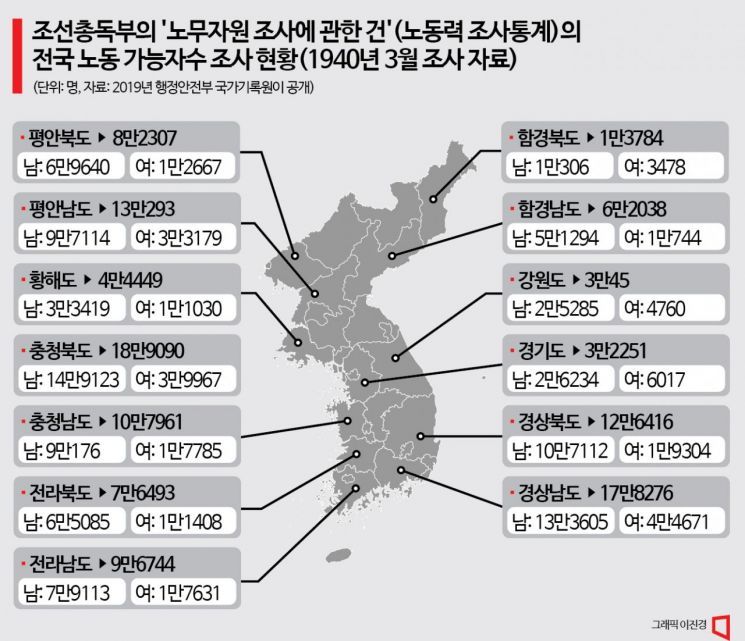

The National Archives of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety released the nationwide survey status of the number of labor-capable individuals from the "Labor Resource Survey" (Labor Force Survey Statistics) conducted by the Government-General of Joseon <March 1940 survey data> in 2019. This data reveals how systematically and comprehensively forced labor was carried out in the 1940s.

The National Archives of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety released the nationwide survey status of the number of labor-capable individuals from the "Labor Resource Survey" (Labor Force Survey Statistics) conducted by the Government-General of Joseon <March 1940 survey data> in 2019. This data reveals how systematically and comprehensively forced labor was carried out in the 1940s.

The Root of Perceptual Differences on the 'Illegality' of Colonial Rule Sealed by the 1965 Korea-Japan Claims Agreement... Resolution Is Difficult

The most sensitive turning point in the perceptual differences between the two countries regarding colonial rule emerged when Japan did not recognize the illegality of treaties (1904, 1905, 1907, 1910 Korea-Japan Agreements), while the Korean government did. Japan interpreted that the Korea-Japan Agreements were valid at the time of conclusion and afterward but became invalid due to Japan's defeat, whereas Korea claimed they were null and void from the outset.

This became the starting point because the 1965 Korea-Japan Claims Agreement process did not resolve or settle this issue or the colonial legacy. However, the 2018 Korean Supreme Court ruling sharply exposed the temperature difference between the two countries (Korea viewing it as illegal, Japan viewing it as legal at the time of conclusion), and since then, Japan has insisted solely on its own position regarding the forced mobilization issue.

The conservative and right-wing shift in Japanese academia and politics in the mid-to-late 1990s fueled this further. Starting with Norihino Kato's 1995 book "Post-Defeat Theory," historical revisionism gained ground amid security crisis rhetoric. Relativistic discourses such as "Let's abandon self-deprecating history," and "Mourning one's own dead enables mourning others" appeared. These appealed to Japanese voters who desired a 'strong Japan.' There is also a view that the Liberal Democratic Party needed nationalism and far-right forces to frame the increased wealth gap caused by neoliberalism at the time.

The conservative and right-wing shift in Japanese academia and politics in the mid to late 1990s added fuel to this. Starting with the book "Post-Defeat Theory" written by Katonorihino in 1995, historical revisionism and security crisis theories gained prominence. Relativistic discourses such as "Let's abandon the self-deprecating view of history" and "One can mourn foreign victims based on first mourning their own country's deceased" emerged.

The conservative and right-wing shift in Japanese academia and politics in the mid to late 1990s added fuel to this. Starting with the book "Post-Defeat Theory" written by Katonorihino in 1995, historical revisionism and security crisis theories gained prominence. Relativistic discourses such as "Let's abandon the self-deprecating view of history" and "One can mourn foreign victims based on first mourning their own country's deceased" emerged.

Because the government dragged the issue for 25 years before finally announcing a forced mobilization compensation plan, questions arise as to whether it was the best option and whether there will be a corresponding response from Japan. On the fundamental foundation of the 1965 Korea-Japan Claims Agreement, which views colonial rule as legal, it is difficult for Japan to make a progressive change in stance, and complete resolution is unlikely.

Choi Eun-mi, a research fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, pointed out, "The perceptual difference between the two countries regarding colonial rule goes back to the 1965 Korea-Japan Claims Agreement, and the source of all problems is that the illegality and legality of colonial rule have not been resolved by 'Agree to Disagree.' From there, the difficulties of settling historical issues repeat."

Therefore, it is viewed as unlikely that Japan will take sincere follow-up measures responding to the Korean government's 'big-hearted decision' on sensitive issues such as visits to Yasukuni Shrine or the Dokdo territorial dispute. Even if there are mentions of past issues, it is highly likely that only 'level-controlled' measures will be taken. Professor Hosaka Yuji of Sejong University predicted, "Because the Dokdo territorial dispute and Yasukuni Shrine visits are core issues for Japanese right-wing forces, it is difficult to expect a response in those areas."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)