Will the Global Economy Become a White Swan?

Export Scale Last Year: 797 Trillion Won

201 Times Growth Compared to the First Oil Shock

Experts "Concerns if Prolonged

Companies Will Lose Production Opportunities, Manufacturing SMEs Will Be Hit"

Krugman "Not Yet at Disaster Level

Food Is a Bigger Issue Than Energy"

Export Scale Last Year: 797 Trillion Won

201 Times Growth Compared to the First Oil Shock

Experts "Concerns if Prolonged

Companies Will Lose Production Opportunities, Manufacturing SMEs Will Be Hit"

Krugman "Not Yet at Disaster Level

Food Is a Bigger Issue Than Energy"

[Asia Economy Reporters Kim Hyun-jung, Park Byung-hee] If a third oil shock hits the global economy, South Korea, which has a high energy import volume and a high export ratio relative to its economic size, is expected to suffer considerable damage. However, domestic and international experts agree that compared to the first and second oil shocks, this is a predictable risk, and with improved consumption elasticity, the situation is unlikely to deteriorate rapidly in the short term.

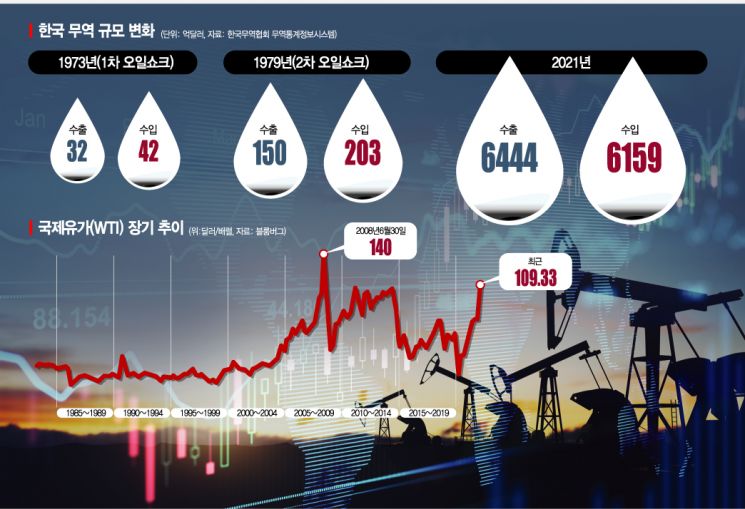

According to the Korea International Trade Association's Trade Statistics Information System on the 14th, South Korea's export scale last year was $644.4 billion (approximately 797 trillion won), about 201 times and 43 times larger than in 1973 ($3.2 billion) and 1979 ($15 billion), when the first and second oil shocks occurred. The export ratio relative to real GDP, which was in the 10% range in the 1970s, now exceeds 40%. Especially, South Korea's current economic structure, summarized as 'manufacturing export-centered,' is considered vulnerable to risks from fluctuations in international oil prices and raw material costs.

◆ Productivity Impact if Prolonged... Investment and Employment Also Worsen= International oil prices are already soaring. Due to Western sanctions on Russian energy following the Ukraine invasion, on the 8th (local time), the April West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil price on the New York Mercantile Exchange briefly rose to $129.44 per barrel before closing at $123.70. This is the highest closing price since August 2008.

The oil shocks of the 1970s hit the South Korean economy, which was less dependent on foreign trade compared to now. Particularly, at that time, South Korea was transitioning its government economic development plan from light industry to heavy and chemical industries, which added to the shock. As a result, the economic growth rate, which was 12.8% in 1973 compared to the previous year, fell to 8.1% in 1974 and 6.6% in 1975. After the second oil shock in 1980, the growth rate dropped to -2.7%. Exports were also hit, with the export growth rate falling from 98.6% in 1973 to 24.8% in one year. Meanwhile, the consumer price inflation rate jumped from 3.5% to 24.8% during the same period.

The surge in oil prices due to Western sanctions on Russia is expected to affect South Korea's export competitiveness, which is more synchronized (coupled) with the global market than in the past.

Jung Min-hyun, a senior researcher at the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP), explained, "The oil shock immediately acts as inflationary pressure and causes cost increases in production. The biggest concern is if this situation prolongs, even if production will and technology are secured, production opportunities are lost due to lack of raw materials." He added, "In this case, productivity practically deteriorates, leading to structural problems that can reduce investment and employment. Especially, small and medium-sized enterprises in the manufacturing sector with a high export ratio will be hit."

Concerns also arise because high oil prices are likely to persist for some time. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies (OPEC+) show little willingness to increase production, and U.S. shale producers are not actively considering increasing crude oil output. Kim So-hyun, a researcher at Daishin Securities, said, "To determine whether international oil prices will trend downward, signals such as the end of the Russia-Ukraine war or a decline in crude oil demand must appear. Although demand decline is seen mainly in refining and chemical companies, the decrease is still limited."

◆ Krugman: "Not Yet at Disaster Level"= However, the prevailing opinion is that the likelihood of an oil shock causing inflation at the level seen in the past is low.

Bloomberg supported this analysis by citing that ▲the global economy's dependence on oil is lower than in the 1970s, ▲the U.S. federal funds rate was 3% during the oil shocks, and ▲the second oil shock was triggered by the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Paul Krugman, Nobel laureate in Economics in 2008 and professor at the City University of New York, wrote in a New York Times column on the 8th that while sanctions on Russia will be a negative factor for the global economy, it will not reach disaster levels. He particularly noted that the likelihood of a shock comparable to the 1970s oil shocks is low. Krugman pointed out that although Russia is a major crude oil producer, it accounts for only 11% of the global market. Compared to the 1970s when Middle Eastern countries accounted for nearly one-third of global oil production, Russia's influence is not large. He also assessed that since Russia and Ukraine have a significant share in wheat production, food might be a bigger issue than energy.

Jung Min-hyun explained, "The first and second oil shocks were unexpected and stronger supply shocks than anticipated. However, the shock from Western sanctions on Russia was somewhat expected and there is capacity to respond." He added, "In the past, dependence on fossil fuels was high, there were no eco-friendly energy technologies, and energy efficiency was poor. Currently, consumption elasticity has greatly improved, such as the capacity to produce alternative energy resources when oil price shocks occur."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.