DGIST Research Team Uncovers Neurological Mechanism of Animal Odor Receptors

Attracted to Low Concentrations but Avoids High Concentrations

First in the World to Confirm a Single Receptor Detects Odors at All Concentrations and Directs Behavior

Perfume. Stock photo. Not related to the article.

Perfume. Stock photo. Not related to the article.

[Asia Economy Reporter Kim Bong-su] Perfume smells pleasant when applied moderately, but if applied excessively, it can be perceived as a foul odor. Domestic researchers have uncovered why animals exhibit different reactions depending on the concentration. Contrary to previous theories, they confirmed that a single receptor detects odors at all concentrations and directs behavior, showing attraction at certain concentrations but avoidance at high concentrations.

The joint research team of Professors Kim Gyu-hyung and Moon Je-il from the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) announced on the 5th that they identified the neurological mechanism by which animals perceive and respond to the same odorant as either pleasant or foul depending on its concentration. This is expected to provide clues for future research on the complex olfactory processing in humans.

Perfume smells pleasant when applied moderately but can be perceived as foul if overused. Similarly, animals show attraction to certain concentrations of various odorants but exhibit avoidance behavior at other concentrations. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying this concentration-dependent switch in olfactory behavior.

Molecular and Neural Circuit Mechanisms Regulating Concentration-Dependent Olfactory Behavior to DMTS in Caenorhabditis elegans

Molecular and Neural Circuit Mechanisms Regulating Concentration-Dependent Olfactory Behavior to DMTS in Caenorhabditis elegans

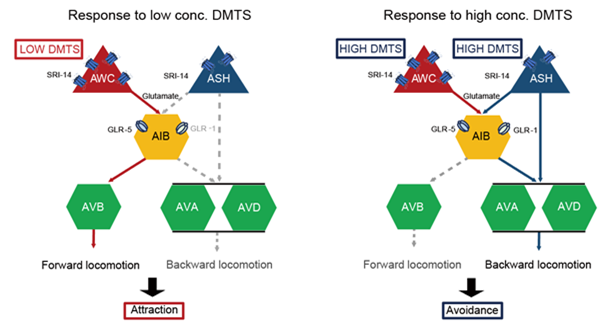

The research team studied the olfactory behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans (hereafter referred to as C. elegans) toward a sulfur compound called DMTS (Dimethyl trisulfide). DMTS is a smell component found in aged kimchi. The team confirmed that C. elegans shows preference responses to low concentrations of DMTS but avoidance responses at high concentrations.

They also investigated how C. elegans distinguishes concentrations of the same sulfur compound and exhibits opposite behavioral patterns depending on the concentration. They identified a mutant worm that could not detect the smell of DMTS; this mutant had a defective olfactory receptor called ‘SRI-14’. It was revealed that this olfactory receptor is necessary for both avoidance behavior at high concentrations and preference behavior at low concentrations.

Furthermore, the team conducted various genetic and neurobiological experiments to determine in which neurons the ‘SRI-14’ olfactory receptor functions. As a result, they found specific sensory neurons that detect low and high concentrations of DMTS, respectively.

Interneurons located in the head of C. elegans function similarly to the human cerebral cortex by integrating and regulating sensory information. The research team discovered that a single interneuron connects to each sensory neuron detecting DMTS and processes signals from both low and high concentrations, ultimately leading to appropriate concentration-dependent behavior.

The team broke the existing theory that different receptors exist for different concentrations of odorants causing opposite olfactory behaviors, revealing for the first time worldwide that a single receptor detects all concentrations and that this information is processed in downstream neural circuits to induce olfactory behavior.

Professor Kim Gyu-hyung stated, “This study provides a groundbreaking answer to how animals distinguish concentrations of the same odorant,” adding, “We expect this research to offer clues for studies on how humans differentiate the intensity of the same odorant and for understanding the complex olfactory processing in humans.”

This research was published in the international biology journal 'Current Biology' on the 13th of last month.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)