Cultural Heritage Administration and Buddhist Cultural Heritage Research Institute Launch Nationwide Survey of Buddhist Altars

Symbolic Representation of Mount Sumeru Where Buddha Taught

Lotus, Peony, Elephant, Phoenix, and Other Motifs Embellish the Altars

Exploring Preservation, Restoration, and Management Strategies

Four Surveyed Altars Expected to Be Designated as Treasures

The Buddhist altar is also known as the Sumi altar. This is because it is a symbolic representation of Mount Sumeru, where the Buddha delivered teachings to the four assemblies. It expresses religious symbolism and its imagery in a three-dimensional form. Various iconographies and patterns are depicted using sophisticated carving techniques. The most frequently engraved motifs are flowers such as lotus, peony, and chrysanthemum. There are also depictions of terrestrial animals (birds, lions, elephants) representing the nine mountains surrounding Mount Sumeru, aquatic animals (fish, crayfish, turtles) symbolizing the eight seas, as well as mythical creatures such as dragons and phoenixes. Ritual objects used in Buddhist ceremonies, such as mokpae (wooden plaques), sotong (bamboo tubes), and myeonggyeongdae (mirror stands), are harmoniously combined with upper architectural structures like the cheongae (canopy), creating a majestic atmosphere.

Until recently, Buddhist altars were regarded merely as components of Buddhist architecture and did not receive as much attention as Buddhist statues or paintings. While the Sumi altar at Baekheungam Hermitage of Eunhaesa Temple in Yeongcheon, North Gyeongsang Province (Treasure No. 486) and the Sumi altar at the Daewoongjeon Hall of Jikjisa Temple in Gimcheon, North Gyeongsang Province (Treasure No. 1859) have been designated as national cultural properties, these represent only a small fraction compared to the total number of Joseon dynasty Buddhist architectural structures that have been designated. From last year until 2024, the Cultural Heritage Administration and the Buddhist Cultural Heritage Research Institute are conducting a "Comprehensive Survey of Buddhist Altars in Temples Nationwide." This project aims to establish basic data such as the status of Buddhist altars, as well as detailed specifications and digital images, in order to explore methods for their preservation, restoration, and management.

Fifteen Buddhist altars were surveyed last year. This was the first documentation of their interiors and structures, providing a wide range of information, including the types of internal structural materials, external decorative materials, and wood species used for each component. The Cultural Heritage Administration stated, "We conducted humanities-based research, original digital documentation, conservation science investigations, and safety inspections in parallel," adding, "We also examined the decorative elements of the altars, such as Buddha plaques and sotong, to identify the original appearance of the altars and the locations of their original decorative components."

It is estimated that Buddhist altars first appeared in Korea around the 15th century. As Buddhist rituals developed and the number of ceremonies increased, larger spaces were required, leading to the placement of Buddhist statues and offerings together. The Cultural Heritage Administration explained, "Given that all Buddhist altars were installed in temples rebuilt after the Imjin War (1592-1598), it is highly likely that they became standard architectural structures in the 16th century."

Among the altars surveyed last year, four are expected to be designated as Treasures. These are the Buddhist altars at Daewoongjeon Hall of Hwaeomsa Temple in Gurye, Bogwangjeon Hall of Sunglimsa Temple in Iksan, Geungnakbojeon Hall of Muwisa Temple in Gangjin, and Gukrakjeon Hall of Hwaamsa Temple in Wanju. Park Suhee, a researcher at the Division of Tangible Cultural Heritage of the Cultural Heritage Administration, stated, "The original forms are well preserved, and the carving techniques are highly sophisticated, giving them great historical and artistic value," adding, "Once the survey is completed, we will be able to consider their designation as national cultural properties."

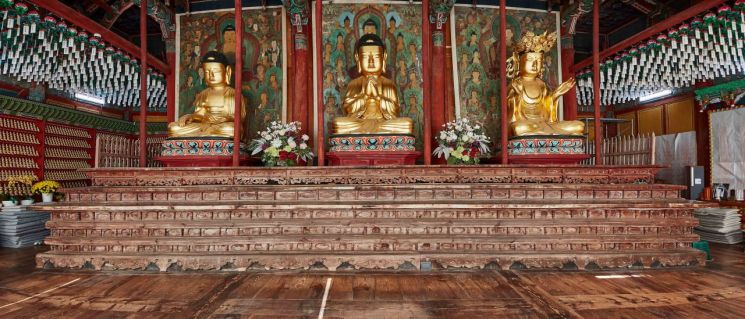

The Daewoongjeon Buddhist altar at Hwaeomsa Temple features a unique internal structure combined with the pedestal section. In general, Buddhist altars are constructed with pillars, beams, and walls as their basic structure. A separately crafted pedestal and Buddhist statue are enshrined on a rectangular ceiling board. The Hwaeomsa altar is structured with pillars, beams, and walls, and the pedestal and its supporting framework are integrated into the altar's structure at the statue's location.

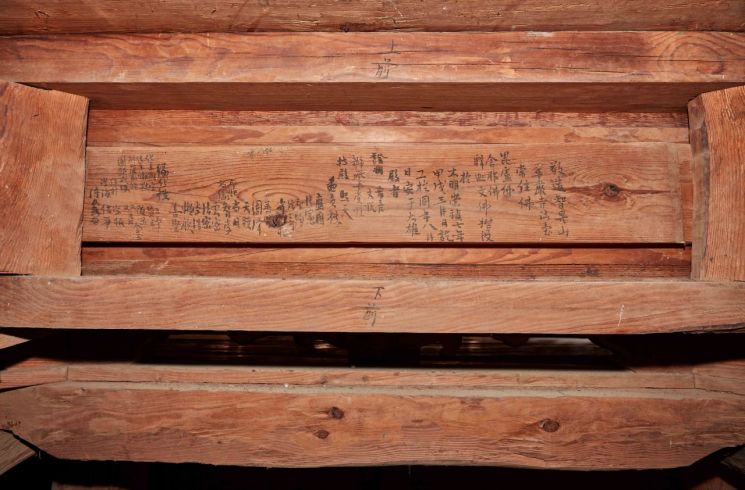

The Cultural Heritage Administration explained, "It appears that the pedestal structure was integrated into the altar's ceiling board during the creation of the Buddhist statues to stably support the weight of three large wooden statues, each nearly 3 meters tall, and their wooden pedestals." They further added, "Through the manuscript recorded on the front of the pedestal of the Nosanabul (Vairocana Buddha), we were able to confirm that the statues and the pedestal were created together in 1636."

The Bogwangjeon Buddhist altar at Sunglimsa Temple is supported by cylindrical corner pillars at its four corners, which hold up the canopy. On the upper platform, where the Buddhist statue and offerings are enshrined, a square ceiling board and a 'ㄷ'-shaped beam support are placed. The central section, corresponding to the body, is divided into three tiers with two horizontal rails. Each tier is separated into compartments by inserting vertical posts. The lower platform, which supports the altar, consists of a long beam serving as legs, a base platform, and a lower support beam. The Cultural Heritage Administration noted, "Of the five pillars at the front of the altar, only two are joined with the beam components, while the others were inserted into artificial grooves made in the upper part of the rear panel of the three-tiered central section," adding, "This appears to have been altered during later repairs."

The Geungnakbojeon Buddhist altar at Muwisa Temple, like the Bogwangjeon altar at Sunglimsa Temple, is slightly narrower in width and taller in height. The Cultural Heritage Administration explained, "It shows the proportions and differences characteristic of Buddhist altars made after the 17th century." No well floor was installed beneath the altar. Instead, thick stones were arranged in a rectangular shape, presumed to serve as the stone pedestal. The lower wooden platform was placed on top of the stone base. Three components were connected at the front and rear of the lower platform, with one component placed on each side. Beneath the lower platform, a thick layer was added to support the weight of the rear wall, raising the platform. The Cultural Heritage Administration stated, "Decorative components were added to conceal the joints, but these do not appear in photographs from the Japanese colonial period," explaining, "They were added before the 1982 restoration."

The Gukrakjeon Buddhist altar at Hwaamsa Temple is generally red, but only the compartments feature black lacquer. The upper horizontal panel is decorated with openwork carvings of lotus flowers and pomegranates, while the central section features openwork floral designs only on the first tier. No rear wall was installed in the rear compartment, but a Buddhist painting mounted on a flower panel behind the statue appears to serve as the rear wall. The painting is placed on top of the ceiling board, making the rear of the altar visible. The rear of the altar has a three-tiered central section, like the front, but without vertical posts or openwork carvings. Additional frames and panels were attached above the rear corner frame, creating a stepped difference. As a result, part of the lower platform at the rear of the altar is obscured.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.