[Asia Economy Reporter Choi Seok-jin] From now on, most complaints and accusations must be submitted to the competent police station. Also, only by exercising the right to appeal against the police’s decision not to prosecute can the prosecution receive the case records and review the case once again.

According to the prosecution and police on the 3rd, from the 1st of this month, amended laws containing the adjustment of investigative authority between the prosecution and police were simultaneously enforced, significantly changing the criminal justice system.

With major changes to the Criminal Procedure Act and the Prosecutors’ Office Act, including the abolition of the prosecution’s investigative supervision authority, there have been significant changes in the relationship between the prosecution and police. The enforcement of presidential decrees such as the “Regulations on Mutual Cooperation and General Investigation Principles between Prosecutors and Judicial Police Officers,” “Regulations on the Scope of Investigation Initiated by Prosecutors,” and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety’s “Police Investigation Rules” has drastically reduced the scope of prosecution investigations.

Prosecution’s Investigation Scope Limited to ‘Six Major Crimes’... Only Some Within These Six

Now, the primary investigative authority for most cases lies with the police.

The prosecutor’s direct investigative authority is limited under the amended Article 4 (Duties of Prosecutors) Paragraph 1 of the Prosecutors’ Office Act to six major crimes: ▲corruption crimes ▲economic crimes ▲public official crimes ▲election crimes ▲defense industry crimes ▲large-scale disasters, as well as ▲crimes committed by police officers and cognizable crimes directly related to these crimes or crimes referred by the police. All other crimes are investigated by the police.

However, prosecutors cannot investigate all crimes that fall under these categories indiscriminately.

The scope of the prosecutor’s investigation is further restricted by the presidential decree “Regulations on the Scope of Investigation Initiated by Prosecutors” and the administrative rule “Administrative Rules on the Scope of Investigation Initiated by Prosecutors.” For example, in corruption crimes, bribery cases can only be investigated by prosecutors if the total amount of bribes received is 30 million KRW or more. For crimes such as bribery under the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Crimes (Special Act), violations of the Attorney-at-Law Act, or violations of the Political Funds Act, prosecutors can investigate only if the total amount involved is 50 million KRW or more.

In economic crimes, only those involving gains of 500 million KRW or more, such as fraud, embezzlement, and breach of trust, which fall under the Special Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes, can be investigated by prosecutors. In cases of tax evasion, direct investigation by prosecutors is possible only if the evaded tax amount subject to the Special Act is 500 million KRW or more annually.

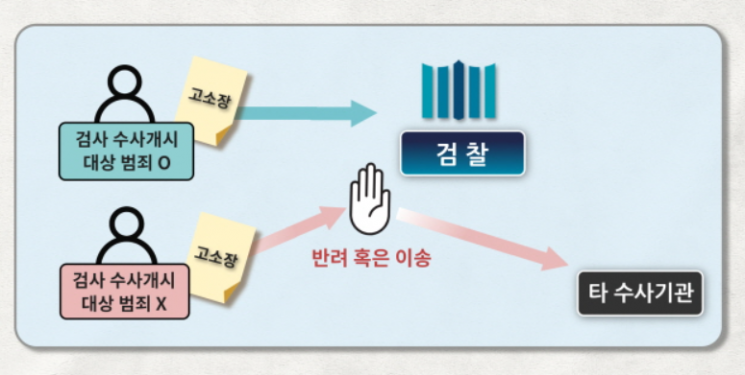

Submit Complaints to the Competent Police Station... If Submitted to Prosecution, It Will Be Returned or Transferred

Until last year, complainants who suffered direct damage from a crime or third-party accusers could submit complaints or accusations to either the prosecution or the police.

Most cases received by the prosecution were then directed to the police for investigation under the supervision and control of the prosecutor.

In other words, prosecutors were involved in the entire investigation process, including requests for search and seizure warrants, arrest warrants, decisions on prosecution, evidence collection, and witness interviews.

However, under the new system starting this year, the types of crimes that the prosecution and police can investigate are distinguished from the outset, so the institution that receives and investigates the case is determined based on the type of crime and the amount involved at the complaint submission stage.

That is, for crimes other than the six major crimes that the prosecution can directly investigate and crimes committed by police officers, complaints or accusations submitted to the prosecution will be rejected.

The prosecution will inform the complainant that the case is not within the prosecution’s investigative jurisdiction and advise them to submit it to the competent police station, thereby rejecting the submission. If the complainant insists on submitting the complaint to the prosecution or submits it electronically, the case will be transferred to the police for investigation.

If part of the submitted complaint or accusation does not fall under the prosecutor’s investigation initiation crimes, only that part may be transferred to the police, or the entire complaint may be transferred.

Currently, cases under prosecution supervision have been uniformly transferred to the police. Although some cases have been ordered for supplementary investigation, ultimately all cases currently under police investigation have been transferred to the police.

Also, if the prosecution becomes aware of high-ranking public official crimes subject to investigation by the High-ranking Public Officials Crime Investigation Office (HPOC), expected to be launched in January, it must immediately notify the HPOC, and if the HPOC chief requests the transfer of the case, the prosecution must comply.

Police’s Authority to Close or Suspend Investigations... Must File an Appeal

One of the most noticeable changes this year is the police’s authority to close investigations.

Until now, even if the police judged that there was no suspicion against a suspect in an ongoing investigation, they could not close the case on their own. They had to send the case to the prosecution with a “no suspicion” or “non-prosecution opinion,” after which the prosecutor reviewed the case records and made the final decision to either dismiss or order a reinvestigation by the police.

However, under the new system, cases are sent to the prosecution only if the police determine that there is sufficient suspicion, and the prosecutor decides whether to prosecute. If the prosecutor deems supplementary investigation necessary to decide on prosecution, the case may be returned to the police for supplementary investigation, or the prosecutor may continue direct investigation while requesting only necessary assistance from the police.

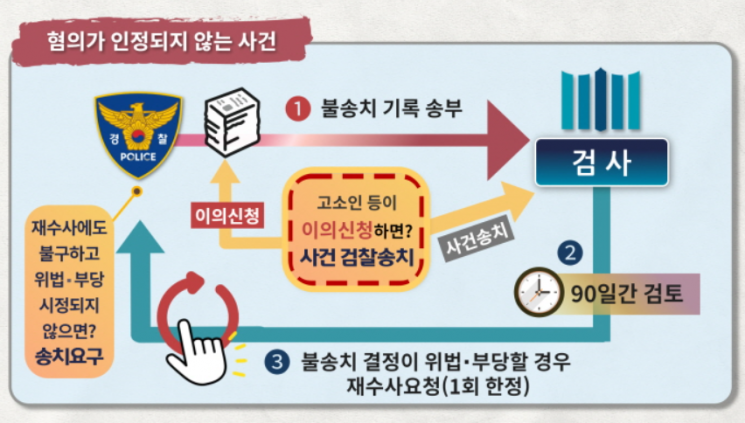

Conversely, if the police determine that there is no suspicion, they can close the case themselves by issuing a non-prosecution decision.

If the complainant or accuser files an “appeal” against the police’s non-prosecution decision, the case is sent to the prosecutor, who reviews it again and decides on prosecution after supplementary investigation if necessary.

Additionally, when the police make a non-prosecution decision, they must send the prosecutor a non-prosecution decision document stating the reasons for non-prosecution, along with a complete list of seized items, record lists, and related documents and evidence, pursuant to Article 62 (Non-prosecution of Cases by Judicial Police Officers) Paragraph 1 of the “Regulations on Mutual Cooperation and General Investigation Principles between Prosecutors and Judicial Police Officers.”

The prosecutor reviews the non-prosecution records for 90 days after the police’s decision and may request reinvestigation if the non-prosecution decision is illegal or unjust. However, the prosecutor can only request reinvestigation once.

Also, if the police cannot locate the suspect or witness during the investigation, they may decide to suspend the investigation. Complainants, accusers, or victims who receive notification of the police’s suspension decision can file an objection with the head of the immediate superior police agency to which the police belong.

Furthermore, the prosecutor reviews the suspension records for 30 days after the police’s suspension decision to determine whether the decision violates laws, infringes on human rights, or constitutes abuse of investigative authority, and may request corrective measures from the police if necessary. Complainants, accusers, or victims who believe the police’s suspension decision violates laws, infringes on human rights, or constitutes significant abuse of investigative authority may report this to the prosecutor.

Attorney A said, “In the past, even if complainants or accusers remained silent, cases with no suspicion concluded by the police would still be sent to the prosecution for a final decision by the prosecutor. Now, it is important to remember that if you do not file an appeal, the case will not be sent to the prosecution.”

Confusion Inevitable Until the System Settles... Concerns Over Vice Minister Lee Yong-gu’s Case

Since the scope of investigation for the prosecution and police is now complexly subdivided by crime type and amount involved, it will not be easy for ordinary citizens to accurately identify the investigative agency and submit complaints or accusations. Some confusion is expected until the system settles.

Meanwhile, there are skeptical views on whether the legislative amendments that drastically reduce the prosecution’s investigative authority and expand the police’s investigative authority as part of “prosecution reform” are necessarily beneficial to suspects under investigation or complainants.

Regarding this, the police’s official position is, “The police now send cases to the prosecution only when there is suspicion of a crime, and can close cases at the first stage if suspicion is not recognized. It is expected that public inconvenience will be reduced as the double investigations routinely conducted by the prosecution to close cases will significantly decrease.”

This can be interpreted as meaning that the past problem where suspects or witnesses had to be interviewed twice?once by the police and again by the prosecution after the case was sent to the prosecution?may be eliminated.

However, there are also concerns about side effects.

Until now, the quasi-judicial prosecutor was involved in the conclusion of cases in some way, but now that the police can close cases independently without the prosecutor’s involvement, there are criticisms that cases might be covered up, as in the recent case of Vice Minister of Justice Lee Yong-gu’s “drunken assault on a taxi driver.”

The police should have booked Vice Minister Lee, who assaulted a taxi driver while driving or stopped in a drunken state, under the amended Special Act, but instead classified it as a simple assault under the Criminal Act and closed the investigation without booking him, citing the victim’s “request for no punishment.”

When this fact became known and sparked controversy over “lenient investigation,” civic groups filed complaints with the prosecution against Vice Minister Lee, the police investigation team, and an unidentified police official who issued illegal investigation instructions. The case is currently under direct investigation by the Criminal Division 5 (Chief Prosecutor Lee Dong-eon) of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office.

Attorney A expressed concern, saying, “The problem is cases like Vice Minister Lee’s, where the suspect was not even booked. Once the police book a case, it is either sent to the prosecution or, if the police decide not to prosecute, the case records go to the prosecution, giving the prosecution a chance to review it. But if the police do not even book the case, there is no way to control whether the police’s closure decision was appropriate.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.