Taiwanese Cultural Anthropologist and Journalist

Faces of Borderlanders Encountered by Apo

Conflict Arises When Understanding Each Other Is Abandoned

Reflecting Asian Struggles Over Identity

The 'Solution to Conflict' Is Ultimately Meeting and Dialogue

[Asia Economy Reporter Naju-seok] Although the vacation season is approaching, we are living in a new era where overseas travel is out of the question. The reason for overseas travel was to escape daily life and find rest. In this process, we could spend time communicating with 'them' beyond the borders, not ourselves. The growing fear of what lies beyond the borders these days is another aftereffect brought by the novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19).

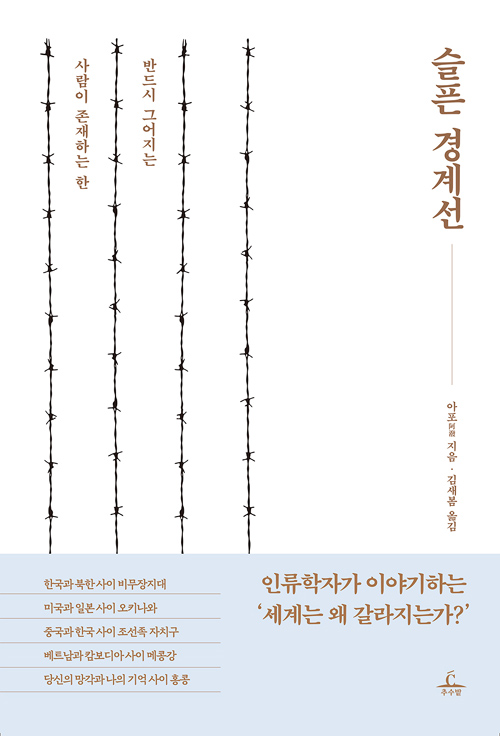

“Sad Borders” is now a story about crossing the increasingly difficult boundaries between countries and ethnic groups. The author is Apo (阿潑), a Taiwanese cultural anthropologist and journalist. He published the book based on his experiences crossing borders between countries in East Asia as well as internal borders within countries.

“Sad Borders” centers on experiences during travel and stories of people met along the way. However, it is difficult to find the usual travel atmosphere or impressions. Instead, anthropology takes the forefront, focusing on the identities of people living across different borders encountered through travel.

We usually draw boundaries in a binary opposition of 'us and them' or 'me and you.' The concept of identity is hard to confirm when it remains only within the existence of the self or within the framework of 'us.' Identity seems to become clearer when facing the other, the 'you' or 'them.'

The people placed on the boundary line of this dichotomy of us and them are the subject of “Sad Borders.” Therefore, the author’s concept of identity, revealed through observing ethnic issues, minorities, and their identities across Southeast Asia, forms the main axis of the book.

The issue of identity is by no means simple. Even in China, there are overseas Chinese who maintain the framework of traditional culture that has disappeared elsewhere. Some suppress their ethnic identity and prioritize the identity of the country they belong to. Amidst various mixed identities, people live on ambiguous borders. For example, do Joseonjok (ethnic Koreans in China) cheer for the Korean team or the Chinese team in a national soccer match? This does not determine their identity.

There is also an interpretation that Okinawa, occupied by the U.S. military after World War II, chose to return to Japan not because they longed for their homeland but as a process of seeking an alternative to humiliating colonial rule. It is explained that they chose Japan because they disliked being treated as a colony by the U.S., not because they liked being Japanese. Without understanding the past and present pain of those living in Okinawa, it is difficult to empathize with their feelings as both Japanese and Okinawans.

The explanation surrounding the identity of those living as Hongkongers, neither Chinese nor British, is also impressive. The author introduces, “It is hard to find a place like Hong Kong, which is dismissed as a ‘century-old colony of a capitalist developed utilitarian society’ anywhere in China or even in overseas Chinese communities worldwide, stubbornly remembering the ‘democracy stillbirth’ (the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen incident) unrelated to themselves.” The book also describes the scenes of Hongkongers flooding the streets on the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen incident and how they keep the memory of June 4 as part of their identity every year.

Hongkongers took to the streets during the Tiananmen incident. Since then, every June 4, they commemorate those who sacrificed their lives on the streets. This formed values and identity as Hongkongers, not as Chinese. Whenever political issues like the extradition bill or the National Security Law arise, Hongkongers stand up shouting for democracy. This is also because they take the Tiananmen incident as part of their identity. This helps to somewhat understand why the Chinese government feels burdened by Hongkongers’ sentiments and why Hongkongers rise up despite oppression.

Identity remains an ambiguous existence. A clear example is that overseas Chinese who are aware of being Chinese and those who are not are scattered across Southeast Asian countries. Although their outward appearances differ, the influence of identity in defining individuals still remains. The author explains this as follows:

“The culture and language of early overseas Chinese immigrants are like the oil floating on the surface of the broth here. It is not actually edible but just floats on the surface as a historical relic. It may seem unified at a glance but ultimately did not melt in, nor was it cleanly removed.”

In the complexly intertwined history and personal life experiences, identity deeply resides in various layers.

Although identity is persistent, conflicts do not arise merely because of belonging to a particular nation or ethnicity. However, if mutual understanding is abandoned, identity conflicts lead to disputes. The solution to conflict is ultimately facing each other.

“Such interactions repeatedly appeared in my experiences of seeing and hearing, creating resonance and stimulation. In the process, I realized that the more one fears understanding others, the more prejudice and violence are replicated, spread, and inherited. The stronger the psychological boundaries, the more conflicts inevitably arise.”

Today, with air and sea routes narrowed by COVID-19, making it harder to face ‘them,’ the threshold for communication has risen, making the borders even sadder.

Sad Borders / Apo / Translated by Kim Sae-bom / Chusubat

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.