10 Years of Netflix: Warning Signs for Profitability and the Ecosystem

Studio Stock Drops Despite "The Glory" Global Success

Production Cost Inflation Deepens Industry Polarization

Government Vows Full Support for IP Ownership and Alternative Models

On January 6, 2016, Netflix's entry into Korea was an event that fundamentally shook the order of the content industry. It went beyond simply sparking competition-the so-called "catfish effect"-and triggered seismic shifts across the entire production, distribution, and revenue structure. Ten years later, K-content has become a global mainstream phenomenon, but behind this dazzling success lies a deep shadow of declining profitability and an increasingly imbalanced ecosystem. Have we truly become a "global content powerhouse," or have we been reduced to a cost-effective "premium subcontracting base"?

Deeper Imbalance as the Market Grows

According to the content and financial investment industries on January 11, the K-content industry has experienced explosive revenue growth through global success, but it now faces a structural limitation where the actual profits accruing to production companies are shrinking. In the production and distribution structure reorganized around global online video services (OTT), domestic production companies have remained in the role of content suppliers, continuously entering into contracts that transfer intellectual property rights (IP) to platforms. In this process, production costs have soared, but most secondary and tertiary revenues generated after a hit accrue to the platforms, leading to the industry-wide sentiment that "even if you make 1 trillion won, nothing is left."

The asymmetry in revenue is the most painful aspect. Netflix covers 100% of production costs and guarantees production companies a margin of about 3-10%. In exchange, the platform monopolizes all IP rights to the work. The structure, in which the platform assumes the risk of a flop, was initially appealing. A stable production environment and a global distribution network offered new opportunities for domestic producers. However, with the emergence of mega-hits like "Squid Game," the limitations of this contract structure have become clear.

Industry insiders estimate that "Squid Game" generated over 1 trillion won in economic value, but the production company, Siren Pictures, earned only enough to cover production costs and a modest management fee. Even as the series continues and theme parks and various spin-off businesses expand, additional revenues accrue to the platform. "The Glory" faces a similar situation. Despite achieving explosive global buzz as the number one non-English TV show, Studio Dragon, the production company, saw its stock price fall immediately after the broadcast. This was because Netflix's monopoly on IP rights meant that neither licensing revenues nor secondary derivative sales from global success could be reflected in the company's books.

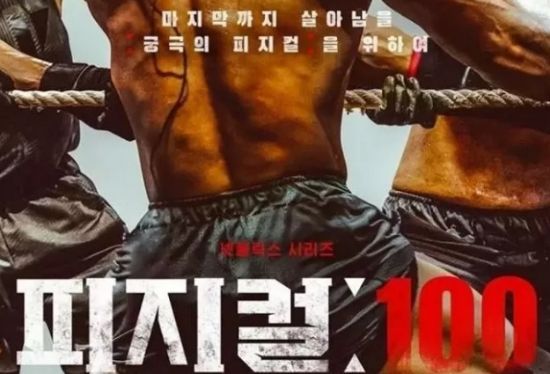

Terrestrial broadcasters are no exception. MBC's variety show "Physical: 100" became the first Korean entertainment program to rank number one in global viewing hours, but MBC itself was left with little to show for it. In the past, broadcasters could expect significant profits by holding IP rights and exporting formats, but now even major broadcasters have been reduced to "premium subcontractors" for Netflix. The practice of handing over the "golden eggs"-the future growth engines-under the pretext of avoiding production cost risks has become entrenched. This is why the apparent global success is disconnected from the fundamental strength of the domestic content industry.

Threats to the Local Content Ecosystem

The resulting production cost hyperinflation, arising from this revenue structure, is becoming a boomerang threatening the local content ecosystem. The rise in production costs cannot be attributed solely to Netflix or actors. It is also an inevitable result of improved working conditions on set, such as the introduction of the 52-hour workweek and the adoption of standard contracts. The real issue is that, in practice, only global big tech capital can bear these higher production cost standards.

Domestic broadcasters and local OTTs with weaker financial resources are being forced to scale back or abandon high-quality drama production. As a result, the market is being reorganized around global platforms, and small production companies and new creators are left with no choice but to exit if they are not selected. The harsh logic that "it is difficult to survive without the backing of big capital" is spreading throughout the industry, deepening polarization.

There are also concerns about the erosion of cultural diversity. Platform algorithms designed for simultaneous global releases and binge-watching tend to favor provocative genres such as thrillers, creature features, and dystopian stories. Long-standing strengths of Korean dramas-melodramas, human stories, and experimental low-budget works-are often excluded at the planning stage for not fitting the "global hit code." This risks weakening the foundation of K-content and could lead to uniformity in themes and formats.

"Contract Structure Modernization Needed"

If the past 10 years proved the "potential" of K-content, the next 10 years will be a battle to secure "practical benefits" and "sustainability." There is a growing call within the industry to move beyond simple supply contracts and modernize contract structures so that production companies can share IP or secure running guarantees. The argument is that only when the success of a work is reasonably returned to production companies and creators can the industry achieve virtuous growth.

Cho Youngshin, Visiting Professor at Dongguk University Media Research Institute, diagnosed, "The Korean content market has entered a harsh adjustment period and will have to endure a 'time of tears' as a consequence of overheating." He added, "Going forward, the market will be divided between mega tentpole projects led by Netflix and mid- to low-budget works focused on efficiency through pre-planning. Rather than simply blaming production costs, we must correct lax production practices and strengthen our fundamentals if we are to survive as a self-sustaining ecosystem-beyond being just a subcontracting base for global platforms."

The role of the government is also becoming more prominent. There are growing calls to foster local platforms to curb the monopoly of global platforms and to establish policy safety nets so that a variety of genres can coexist. The warning is not to become so focused on speeding down the highway built by Netflix that we end up handing over the "steering wheel"-the leadership of the industry itself.

Kim Jihee, Director of the Visual Broadcasting Content Industry Division at the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, stated, "We are significantly expanding the 'OTT-specialized production support' program to help domestic production companies move beyond a subcontracting structure where they only receive production costs and a certain margin while handing over all rights, so that they can jointly own platforms and IP and generate additional revenue." She added, "Since we cannot force global platforms to change their business models, we will focus our policy capabilities on enabling production companies to retain IP sovereignty and utilize diverse distribution channels to create 'alternative success models.'"

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.