Employer Definition and Scope of Labor Disputes Expanded

Law to Take Effect After Six-Month Grace Period

Recently, Company A, which operates in the semiconductor sector, requested a major law firm to “redesign its business structure so that the principal contractor is not recognized as the employer.” The company outsources some of its production processes, and decided to seek legal advice in advance, concerned that if the subcontractor union claims a dispatch relationship and demands direct employment from the principal contractor, it could lead to a significant increase in labor costs.

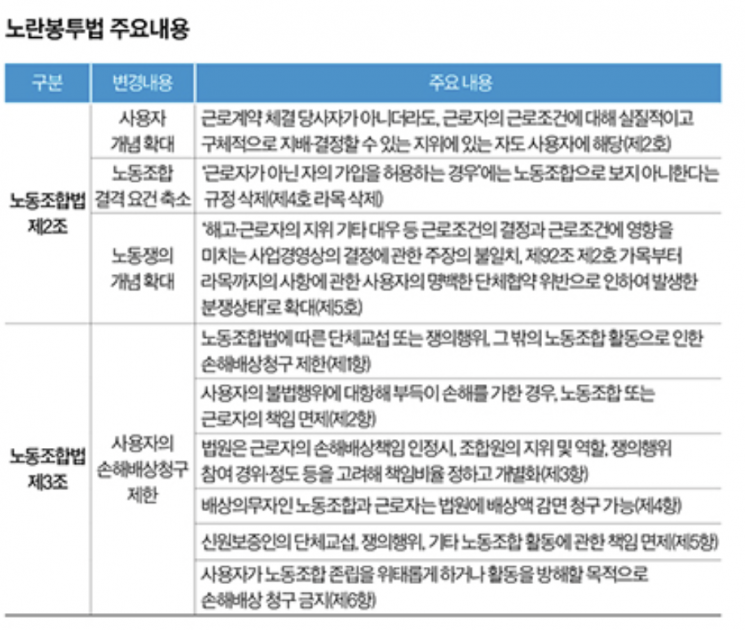

The so-called “Yellow Envelope Act” (Amendment to Articles 2 and 3 of the Trade Union and Labor Relations Adjustment Act) was passed on August 24, 2025. Although companies had begun preparing before the law was enacted, confusion remains in the field, as key issues will ultimately require a Supreme Court ruling to be resolved. In particular, the demand for legal consultation to establish concrete response systems has surged among companies in the semiconductor, construction, and logistics industries.

The most notable feature of the newly passed Yellow Envelope Act is the significant expansion of the concept of “employer.” The revised Article 2, Clause 2 defines an employer as “a person who, even if not a direct party to the employment contract, substantially and specifically controls or determines working conditions.” This means that principal contractors may be obligated to engage in collective bargaining with workers employed by subcontractors or contractors. Kim Sangmin (46, Judicial Research and Training Institute, 37th class), an attorney at Bae, Kim & Lee LLC, stated, “At the stage where substantial control is recognized and bargaining is underway, differences in understanding between labor and management regarding the bargaining unit could lead to disputes such as unfair labor practices due to refusal to negotiate.” Kim also noted, “Standards must be established with reference to previous court precedents.”

The expansion of the scope of legitimate “labor disputes” (revised Article 2, Clause 5) is another factor increasing management risk for companies. The amended law includes as subjects of labor disputes: “disagreements regarding the status of workers,” “disagreements over managerial decisions that affect working conditions,” and “disputes arising from the employer’s clear violation of collective agreements.” This means that managerial decisions related to business restructuring, such as mergers and splits, or organizational restructuring, such as adjustment or consolidation of departments, may also become subjects of labor disputes.

This conflicts with prior Supreme Court precedents, such as the ruling that “mass layoffs cannot be the subject of collective bargaining” (1999Do4893), and the precedent that managerial actions to enhance corporate competitiveness, such as restructuring or mergers, are in principle not recognized as subjects of labor disputes (2003Do687). Lee Kwangsun (51, 35th class), an attorney at Yulchon LLC, said, “Not all managerial decisions will be included as subjects of labor disputes, but there is a possibility that restructuring or relocation of workplaces could be regarded as matters related to working conditions.” He added, “Previously, in the case of mass layoffs, it was sufficient to meet the requirements of the Labor Standards Act, but if such layoffs become the subject of labor disputes, companies may have to bear the burden of strike actions by workers, making layoffs less flexible.”

Experts predict that lawsuits between labor and management will increase significantly for at least two to three years after the law comes into effect. An attorney at a major law firm commented, “Companies where substantial control is unclear are more likely to seek a court ruling rather than respond to bargaining hastily.” Kwon Younghwan (46, 3rd bar exam), an attorney at Jipyong LLC, said, “Currently, it is necessary to comprehensively consider various circumstances to determine whether substantial control exists, making it difficult to predict in advance and likely requiring a court decision.” He also advised, “Since unfair labor practices subject to criminal penalties and administrative sanctions may be involved, it is important to prepare bargaining strategies in advance during the six-month grace period.”

The impact of the Yellow Envelope Act was felt immediately. On August 25, just one day after the law was passed, the Hyundai Steel subcontractor union announced plans for a collective lawsuit against the principal contractor. Business circles raised the possibility of a constitutional complaint, arguing that the scope of employers and labor disputes is unclear and potentially unconstitutional. Hector Villarreal, President of GM Korea, also hinted at the possibility of a re-evaluation of the company’s Korean operations by headquarters, suggesting the potential for withdrawal from the domestic market or a reduction in investment.

The nickname “Yellow Envelope Act” originates from the time when citizens sent donations in yellow envelopes to help Ssangyong Motor workers who had received large compensation judgments after a strike. The Yellow Envelope Act is scheduled to take effect around March next year, following a six-month grace period.

Seo Hayan, Legal News Reporter

※This article is based on content supplied by Law Times.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.