Since 2000, Residents Have Solidified as the 'Vanguard of Struggle'

Recognizing Themselves as Victims of the Low-Fee Medical System

Normalizing Resident Treatment Difficult Due to Health Insurance Financial Status

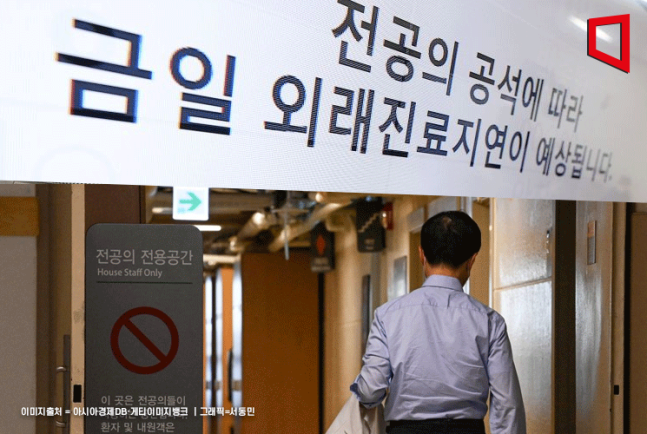

The medical crisis triggered by the simultaneous resignation of residents protesting the increase of 2,000 medical school admissions has reached two months as of the 20th. Despite the government's daily issuance of a dual strategy of hard and soft measures, allowing recruitment of half the increased quota on the 19th, the residents remain steadfast, and even medical school professors have submitted resignation letters, joining the hardline front following their students. We examine the situation mainly from the perspective of the medical community to understand why the resident-led medical service gap crisis is spiraling out of control.

◆Why did the residents take the lead?= Since the residents led the opposition movement against the separation of prescribing and dispensing in 2000, a consensus has solidified over the past quarter-century that residents are the vanguard of government opposition in the Korean medical community. Whenever the medical community engaged in collective action?such as opposing telemedicine in 2014 and public medical schools in 2020?medical students, interns, and residents up to their 11th year simultaneously experienced 'protest participation.' Each time, a collective mindset formed among medical students that 'when I become a resident, I must naturally lead government opposition if necessary,' according to a medical community insider. Currently, medical students who have applied for collective leave are inheriting this experience. Unless this pattern is broken, resident-led collective actions in the medical community are expected to recur.

◆Resident departures as the cause of hospital shutdowns= Hospitals operate like interconnected gears among all professional roles; if one part fails, the entire hospital stops functioning. It is like a rocket exploding if a single screw is missing. One professor’s surgery requires the assistance of two residents. Residents must care for inpatients so that professors can enter the operating room, teach medical school classes, or leave work. It is not simply that university hospitals run deficits because exploited low-wage residents disappear; rather, the 'core personnel supporting work' who back up professors in generating hospital revenue through medical services vanish. This is why professors must take overnight shifts after residents leave.

◆Why residents feel 'justified'= Since the introduction of health insurance in 1977, residents have taken pride in their 'four years of low-wage hard labor' as an essential sacrifice to maintain the medical delivery system under a deficit-prone medical fee system. Currently, medical school professors and specialists all went through residency training, so they empathize with this pride. Residents demanded the replacement of Vice Minister Park Min-su of the Ministry of Health and Welfare as a condition for their return, citing emotional reasons that "some of Vice Minister Park’s remarks disrespected residents and the medical community sacrificing for public health." Critics outside the medical community argue that doctors are playing the victim at the expense of patients. This perception that 'we residents can engage in collective action' will not change unless the fee system is restructured to be profitable.

Residents are holding placards at the 'Group Lawsuit Press Conference Against Park Min-su, a Resident Physician, for Abuse of Authority and Obstruction of Rights by the 2nd Vice Minister of the Ministry of Health and Welfare' held on the morning of the 15th at the Korea Medical Association in Yongsan-gu, Seoul.

Residents are holding placards at the 'Group Lawsuit Press Conference Against Park Min-su, a Resident Physician, for Abuse of Authority and Obstruction of Rights by the 2nd Vice Minister of the Ministry of Health and Welfare' held on the morning of the 15th at the Korea Medical Association in Yongsan-gu, Seoul. [Image source=Yonhap News]

◆Why the medical community is united= All Korean medical institutions are dependent on fees set by the National Health Insurance Service. Regardless of the institution or the level of care, any doctor performing the same treatment receives the same amount. In effect, they are 'employees receiving the same salary from one company.' Although doctors usually have differing interests and conflicts depending on their specialty or institution grade (primary, secondary, tertiary), when policies affecting the entire medical system?such as increasing medical school admissions or the four essential medical packages?are proposed, they uniformly oppose them like 'union members of the same company.'

◆Why persuasion of residents fails= Since 2000, the four medical-government conflicts involving collective action can be divided into two types. The 2014 telemedicine and 2020 public medical school initiatives were 'third-party policy issues' less related to doctors’ economic interests. The medical community viewed telemedicine as a policy breaking the principle that 'doctors directly treat patients' for the benefit of the three major telecom companies. Public medical schools were seen as politically motivated to select medical students recommended by civic groups. In both cases, the government withdrew the policies, and residents returned. In contrast, the separation of prescribing and dispensing reduced doctors’ income, and the medical community ended the strike after receiving promises of fee increases and medical school quota reductions. The current increase in medical school admissions also affects income. However, the government's daily essential medical support measures are not income compensation, so they fail to move residents.

◆Why the outlook for resolution is bleak= Beneath the surface conflict over increasing medical school admissions lies the fundamental problem that maintaining the current health insurance system is difficult. The Park Chung-hee administration introduced health insurance in 1977 based on the 'three lows' principle: low burden, low fees, and low coverage. The medical community accepted this because only 5% of the population was insured at the time, and the government promised gradual fee increases. However, in 1989, the government expanded health insurance nationwide without normalizing fees. The medical community could no longer avoid deficits from health insurance treatments alone. They adapted to the low-fee system by supplementing deficits with non-covered treatments and relying on residents. The good treatment and training environment demanded by the departed residents can only be secured if fees increase enough for training hospitals to run surpluses from medical income alone. However, with health insurance finances expected to be depleted by 2028 due to the impact of Moon Jae-in Care and other factors, such a 'direct solution' is difficult.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)