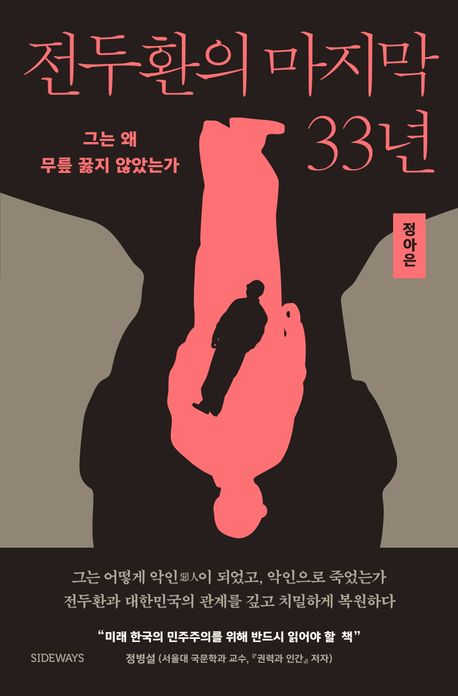

Author Jeong A-eun Publishes 'The Last 33 Years of Jeon Du-hwan'

"Jeon Du-hwan seemed to have a significant lack of ability to confront his own mistakes."

Jeong Ah-eun, the author of 'The Last 33 Years of Jeon Du-hwan,' stated this during a publication press conference held on the morning of the 16th at the Francisco Education Center in Jung-gu, Seoul, explaining, "(Regarding the May 18 Gwangju Uprising) he reacted very childishly to his mistakes, saying things like 'That was a riot' or 'They came down from North Korea to do it.'"

Author Jeong A-eun, writer of 'The Last 33 Years of Jeon Du-hwan,' is speaking at the publication press conference held on the 16th at the Francisco Education Center in Jung-gu, Seoul.

Author Jeong A-eun, writer of 'The Last 33 Years of Jeon Du-hwan,' is speaking at the publication press conference held on the 16th at the Francisco Education Center in Jung-gu, Seoul. [Image source=Yonhap News]

The use of the honorific "Jeon Du-hwan-nim" was intended to neutrally examine the historical and social context that gave rise to Jeon Du-hwan. The author avoided a dichotomous perspective that simply demonizes Jeon Du-hwan or highlights his achievements. She said, "During the writing process, I met many people and asked, 'What do you think about Mr. Jeon Du-hwan?' Some responded seriously, asking, 'Are you referring to former President Jeon Du-hwan?' I thought a lot about the form of address and decided that 'nim' was better than 'ssi'."

Originally, Jeong planned to focus the book on figures such as Jeon Du-hwan, Roh Tae-woo, Roh Moo-hyun, and Moon Jae-in, as it is a rare global case of friends from the same profession rising to the presidency. However, after Jeon Du-hwan’s death, the focus shifted to him. Jeong explained, "Many people felt regret and sorrow over his death. It was a sadness about a situation where communal punishment could no longer be imposed. We investigated what our society had done over the past 33 years, but surprisingly, there was very little material. Most books either focused solely on pointing out mistakes or simply praised him, rather than portraying the era."

The main reason Jeong wrote this book was to explore "Why was there no punishment?" She points to the continuation of the Jeon Du-hwan regime by the Roh Tae-woo government as a cause. She argued, "With an additional five years granted, vested interests became more entrenched. During this time, many records related to the Gwangju victims were also destroyed."

Regarding former President Kim Dae-jung’s decision to pardon Jeon Du-hwan, Jeong criticized it as a political choice on a personal level rather than a legal or judicial judgment. She said, "At the time, President Kim Dae-jung advocated for a pardon to promote harmony between Yeongnam and Honam regions, saying not to seek revenge. This was a decision based on the president’s personal motives rather than law and system. It was also inappropriate for constitutional democracy. I believe it was a decisive moment that missed the opportunity for punishment."

On the issue of Jeon Du-hwan’s grandson, Jeon Woo-won’s apology, Jeong agreed with the view that its significance is diminished because it was not a direct apology from the person involved. Proxy apologies cannot be accepted. However, she added, "Although it is not through law and system, it has affected the spirit and heart. As new evidence and testimonies begin to emerge, a new atmosphere regarding punishment is being created."

Through the book, Jeong identifies fact-finding as an urgent task. She argues that fact-finding must come first to punish those who collaborated with the military dictatorship and still enjoy vast wealth. In this context, she emphasized the importance of accurate historical knowledge. She said, "In culturally advanced countries, when teaching history, they deeply explore modern history closely related to themselves. But we focus more on the history of Joseon. We have had too few opportunities to evaluate social events that happened to us. There is a need to awaken basic awareness."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.