‘Restoration of Ahn Jung-geun Artifacts’ by Leeum Museum Conservation Research Team

Conservation Treatment Results Exhibition on the 28th

Artifact Preservation Work Returns After 110 Years: ‘A Continuous Wait’

"If the writing could come back to life, would it feel like this?"

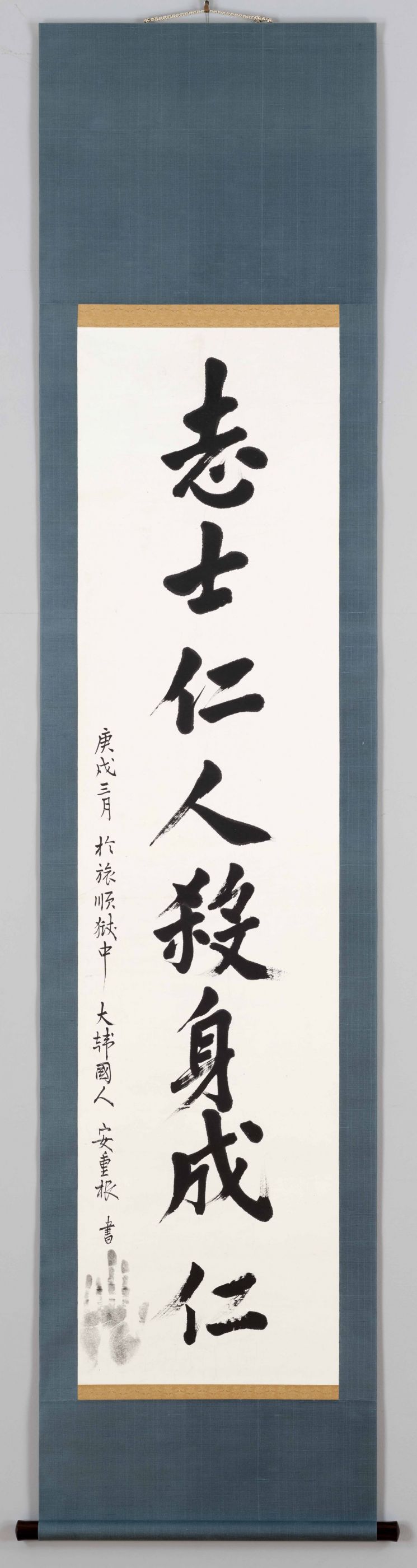

Calligraphy by Ahn Jung-geun after preservation treatment, "Jisainin Salsinseongin".

Calligraphy by Ahn Jung-geun after preservation treatment, "Jisainin Salsinseongin". [Photo provided by Leeum Museum of Art]

On the 24th, the handwritten calligraphy of An Jung-geun, encountered at the Conservation Research Room of the Leeum Museum of Art in Hannam-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul, revealed a vivid presence as if it had just been written on pristine white paper. ‘Jisainin Salshinseongin (志士仁人 殺身成仁).’ An, who personally wrote this phrase from the Analects’ Weiling Gong chapter meaning that a noble-minded scholar and a benevolent person sacrifice their lives for what is right, proved this sentence through his own life. The vivid revival of An’s meticulously crafted calligraphy was accompanied by about a year of conservation treatment. Nam Yumi, the chief of the Conservation Research Room at the Leeum Museum of Art who led the preservation work, laughed and said, “After focusing on An Jung-geun’s calligraphy and photos throughout the year, I eventually went beyond just conserving the object and found myself researching the trajectory of his life and historical materials as if he had become family.”

After a year of conservation treatment, two pieces of An Jung-geun’s prison calligraphy, ‘Jisainin Salshinseongin (志士仁人 殺身成仁)’ and ‘Cheondangjibok Yeongwonjirak (天堂之福 永遠之樂),’ along with a family photo album, will be publicly exhibited from the 28th at the Leeum Museum of Art’s exhibition titled ‘Transcendence ? Meeting Beyond Past and Present, Beyond Borders.’ The preservation work began in January last year through an agreement between the Samsung Foundation of Culture and the An Jung-geun Memorial Hall. Among these, the ‘Jisainin Salshinseongin’ calligraphy was designated as a treasure during the conservation process, marking a double celebration. However, the conservation team felt an even greater responsibility. Chief Nam said, “Since conservation can sometimes be a risky process, we focused solely on cleaning the contaminated parts without causing any deformation or damage to the original calligraphy paper itself.”

Before arriving at the conservation room, the calligraphy showed creases and warping due to the imbalance between the paper and the mounting silk fabric of the scroll. Insects’ secretions were scattered throughout the paper. Considering that An wrote the calligraphy in 1910 and that the scroll was made and stored using Japanese-style mounting methods of the time, such damage was inevitable. Chief Nam explained, “First, we completely dismantled the calligraphy from the scroll, removed the oxidized backing paper, and then began contamination mitigation work. We applied animal glue to the calligraphy area, placed moisture-absorbing paper underneath, and sprayed pure water and distilled water on the contaminated parts to remove the dirt.”

After removing the contamination, the calligraphy was dried and repeatedly mounted and dried on mulberry paper and white paper using the traditional adhesive called gopul (古糊), which is used in paper artifact conservation. The repetition was necessary because of the adhesive strength. Chief Nam elaborated, “Traditional adhesives have lower viscosity and weaker adhesion than regular glue, so repeated applications are required. Using chemical or preservative-added glue can cause chemical changes in the ink, pigments, or paper, shortening the artifact’s lifespan and making conservation difficult. Using gopul minimizes deformation of the artifact, which is why we chose this method.” The gopul used for An’s calligraphy was fermented for over ten years by the Leeum Museum of Art’s Conservation Research Room.

The mounting silk fabric was also replaced with natural materials and stabilized to prevent the calligraphy from warping again. For safe future storage, thick rolled rods (protective tools made to safely preserve scrolls) and paulownia wood boxes were newly produced to improve the storage environment, Chief Nam added.

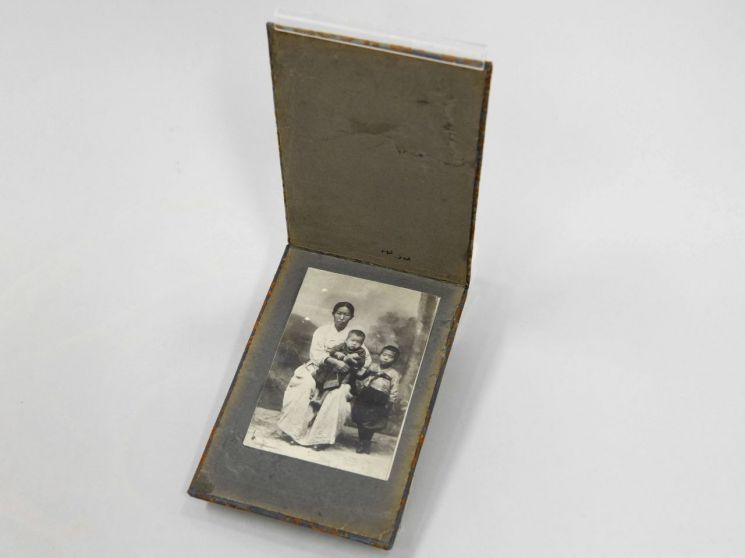

Restoration work on the damaged areas inside the family photo album of patriot Ahn Jung-geun.

Restoration work on the damaged areas inside the family photo album of patriot Ahn Jung-geun. [Photo by Leeum Museum of Art]

The restoration of the photo album, said to be a personal item An Jung-geun looked at to soothe his longing for his family while imprisoned in L?shun Prison, was a continuous challenge. The photo album wrapped in silk had worn corners and a detached cover, inside which faded photos of An’s wife Kim Ah-ryeo and sons Bundo and Jun-saeng were attached. The album had been in Japan after being received directly from An by Sonoki Sueyoshi, who served as an interpreter during An’s trial, or obtained during the process of organizing his belongings, and returned to Korea in January 2020 through a donation by a Japanese collector.

First introduced to the world as part of the Yayoi Museum’s collection in Japan, the album had always been exhibited opening from the left cover. Chief Nam said, “We examined the album referencing previous exhibition materials but found no traces of hinges at the joints. Even after acquiring and analyzing other photo albums produced in Dalian, China, where this album was made, we couldn’t find an answer, which made restoration difficult.”

The inside of a family photo album after preservation treatment. [Photo courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art]

The inside of a family photo album after preservation treatment. [Photo courtesy of Leeum Museum of Art]

During the disassembly of the album, a sudden thought arose: “Why was it only opened sideways?” Trying to see if it might open upwards, they found the answer. Chief Nam explained, “When we considered it as connected vertically, the parts found during disassembly matched perfectly, and everything fit together. After that, the work proceeded smoothly. The worn corners were filled using individual threads from the silk pattern of the cover, and missing parts were supplemented with silk similar to the cover.” There is a theory that the corners wore down because An frequently took out the album to look at his family, but in reality, An only looked at the album two or three times. Chief Nam said, “The wife and two sons in the album came to Harbin to see their father but were suspiciously viewed by Japanese police dressed in hanbok and taken to the local consulate for investigation, during which the photo was taken. Researchers believe the album was made by the L?shun Prison staff who sympathized with An, who had been sentenced to death, and obtained the family photos to show them to An two or three times.”

Nam Yumi, Senior Conservator at the Conservation Research Department of the Leeum Museum of Art, explaining the ink painting preservation process.

Nam Yumi, Senior Conservator at the Conservation Research Department of the Leeum Museum of Art, explaining the ink painting preservation process. Photo by Kim Heeyoon

Nam, with 20 years of experience, and two other experts from the Conservation Research Room described the 13 months of conservation work as “a continuous wait.” Was this referring to the repeated application and drying of gopul to enhance the calligraphy’s preservation, or to the long journey of the artifact, lost for 110 years and now finally returned to its homeland? When asked about his feelings after completing the work, Chief Nam said, “Actually, it wasn’t a highly difficult task. But since it was an external institution’s artifact and An Jung-geun’s relics that had been overseas for a long time and returned, I felt a heavy burden. I couldn’t afford mistakes, excuses wouldn’t work, and the results had to be good. After finishing, I felt very relieved.”

The Conservation Research Room, having completed the work on An’s relics, was busy with other restoration projects that day as well. Chief Nam said, “After this project, we have plans to work with the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation on preserving cultural heritage located abroad. Many overseas cultural properties are in poor condition and remain only in storage, so the main work will be to conserve them in Korea and then send them back. Through conservation work, we hope to raise interest in Korean cultural heritage and continue to lead to further preservation projects.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)