Big Tech Regulation Sword Drawn by US Department of Justice [Global Focus]

[Asia Economy Reporter Yujin Cho] The U.S. government and political circles are intensifying their offensive to regulate big tech. There is a strong stance that legislation is necessary to correct "unchecked power." However, there is also significant opposition. Concerns have been raised that technology companies increase consumer welfare and that preemptive regulation could severely hinder innovation. Can the Biden administration achieve reform of the big tech monopoly structure, which was naturally formed thanks to the government’s policy focus on promotion during the transition to a digital economy?

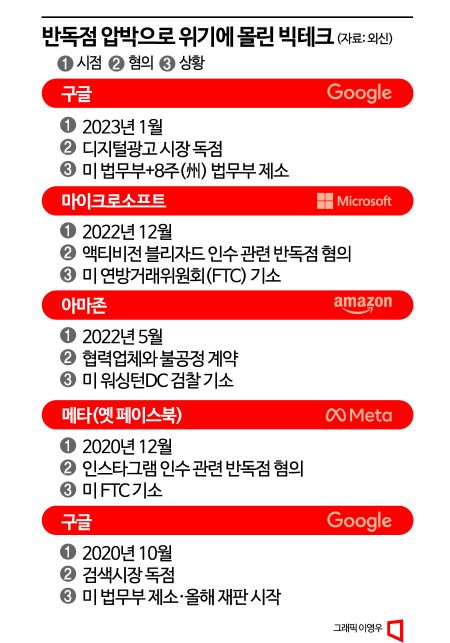

◆ "The era of indulgence is over" = The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) rolled up its sleeves once again this year to regulate big tech. On the 24th of last month (local time), it held a press conference at its Washington DC headquarters and announced it had sued Google, which dominates the global digital advertising market, for antitrust violations and demanded the removal of its advertising business, the largest source of revenue. The DOJ pointed out, "Google used anti-competitive, exclusive, and illegal means to eliminate or weaken threats to its dominance in digital advertising technology."

This lawsuit focuses on whether Google exploited its market-dominant position to gain economic benefits and whether there were abuses such as unfair pricing in transactions with small and medium-sized enterprises. The DOJ believes Google’s monopoly power hinders coexistence and blocks ecosystem development. The DOJ’s lawsuit is based on the Sherman Act (antitrust law). The DOJ views Google, which holds over 90% (95% on mobile) market share in the search engine market, as monopolizing data based on its search service and controlling consumer choice, thereby creating an unfair market.

◆ "Only searching, but verification is difficult?" = However, it is questionable whether the DOJ’s actions will lead to effective sanctions. Foreign policy magazine Foreign Policy recently published a column titled "Big Tech Regulation in Words Only," stating that "there is no substantial legal mechanism to regulate big tech’s business practices overall, and (the U.S. government and political circles’) regulation of big tech is all talk and no action."

Although U.S. regulators are targeting big tech, it is seen as difficult to prove their antitrust harms under the current system. The biggest reason is the lack of clear legal regulatory mechanisms targeting big tech under current law. The Sherman Act, enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1890 to prohibit monopolies in interstate and international trade, is considered inadequate to specifically target big tech.

Due to the nature of the advertising industry, it is difficult to segment the market, and there is insufficient legal basis to prove unfairness. In fact, in 2020, the U.S. FTC sued Facebook for antitrust violations, but the court ruled that there was insufficient legal basis to prove unfairness.

Foreign Policy and other major foreign media point out that the U.S. government’s legal checks on big tech are too late and insufficient. Key antitrust bills led by the White House and the Democratic Party last year mostly failed to pass Congress due to conservative public opinion. There was only a cacophony of debates over the level and scope of big tech regulation.

Currently, several bills are pending in Congress, including the "American Innovation and Choice Online Act," which contains comprehensive regulations on big tech’s self-preferencing, a bill that blocks M&A attempts to eliminate competitors in specific markets, and the "21st Century Antitrust Act," which prohibits companies with a market capitalization over $100 billion from acquiring competitors.

Although the Biden administration, which has passed the midterm point, shows strong determination for big tech reform led by the "New Brandeis" school, there are even forecasts that achieving substantial results will be difficult. Representatives of the New Brandeis school include Lina Khan, FTC Chair known as the "Amazon Reaper," Jonathan Kanter, DOJ Antitrust Division Chief known as a Google adversary, and Tim Wu, Special Advisor for Technology and Competition Policy at the White House National Economic Council and author of "The Curse of Bigness."

The New Brandeis school, which believes "big companies are inherently evil," is named after U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who fought monopolies in the early 20th century. They argue that oversized companies hinder technological innovation, market development, and worker interests, and advocate for breaking up companies to correct these harms. They were strong antitrust advocates who blocked mergers between two distributors in 1966 because the merged entity would exceed an 8% market share.

◆ Legislative gridlock amid power division = Starting this year, with the House of Representatives, which holds legislative authority, shifting to Republican control, there are forecasts that passing pending big tech regulation bills will become even more difficult. Some even claim that big tech regulation is "corporate bashing" by President Biden, who is seeking re-election.

Herbert Hovenkamp, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and an antitrust law expert, analyzed, "Today’s abuse of monopoly power by big tech differs from the past when giant cartels like Rockefeller’s Standard Oil imposed predatory high prices causing consumer harm." He argues that there is little basis to punish companies that increase consumer benefits through low prices and free shipping (Amazon) or provide free communication platforms (Meta, Twitter, etc.). The UK Economist pointed out, "There is also considerable opposition arguing that big tech actually increases consumer welfare."

Meanwhile, countries around the world are focusing on proving that big tech’s monopoly harms can lead to consumer damage, but it is not easy. Last year, the European Union (EU) regulatory authorities passed the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) to achieve this goal. German regulators are enforcing the stronger German Competition Act Article 19a, which is more stringent than the EU’s DMA and DSA. However, no penalties have yet been imposed under these laws.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![User Who Sold Erroneously Deposited Bitcoins to Repay Debt and Fund Entertainment... What Did the Supreme Court Decide in 2021? [Legal Issue Check]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026020910431234020_1770601391.png)