Will the Micro-Macro Crossing Universe Become a Reality?

Institute for Basic Science Successfully Observes Quasiparticles in Visible Matter

Institute for Basic Science Successfully Observes Quasiparticles in Visible Matter

[Asia Economy Reporter Kim Bong-su] Domestic researchers have confirmed that phenomena previously thought to occur only in the microscopic world governed by quantum mechanics also take place in the macroscopic world.

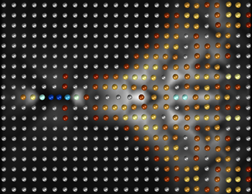

Computer simulation of hydrodynamic crystals. In hydrodynamic crystals, particle pairs (the orange and yellow particles on the far left) cause the particles behind them to oscillate, generating sub-particles that spread out in a cone shape similar to what can be seen behind a supersonic jet. *The colors represent the strength of the particle pairs. (Blue, indicating particles that are close to each other, has the greatest strength, followed by red, yellow, and white as the distance increases and the strength decreases.) The white background represents their velocity. Image courtesy of the Institute for Basic Science.

Computer simulation of hydrodynamic crystals. In hydrodynamic crystals, particle pairs (the orange and yellow particles on the far left) cause the particles behind them to oscillate, generating sub-particles that spread out in a cone shape similar to what can be seen behind a supersonic jet. *The colors represent the strength of the particle pairs. (Blue, indicating particles that are close to each other, has the greatest strength, followed by red, yellow, and white as the distance increases and the strength decreases.) The white background represents their velocity. Image courtesy of the Institute for Basic Science.

The Institute for Basic Science (IBS) announced on the 26th that a research team led by Research Fellow Park Hyuk-kyu (Professor of Physics at Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, UNIST) and Group Leader Zvi Tlusty (Professor of Physics at UNIST) discovered particles moving in pairs in the macroscopic world visible to the naked eye.

Until now, such phenomena were believed to occur only in the microscopic world where quantum mechanics applies. This research suggests that various peculiar quantum mechanical phenomena observed in the microscopic world may also exist in the macroscopic world. Since the advent of quantum mechanics, physics has been divided into classical physics and quantum physics. While classical physics deals with the macroscopic world, such as how visible objects move, quantum physics addresses unique phenomena occurring in the microscopic world, such as atoms or electrons, which are the smallest fundamental particles that make up matter.

For example, materials like solids or liquids have particles closely spaced, resulting in strong interactions. Under conditions where quantum mechanics applies, unique collective phenomena occur where constituent particles cluster together. These are called quasiparticles. This allows groups of strongly interacting particles to be simply described as quasiparticles that behave as if they do not interact. Examples of quasiparticles include Cooper pairs (pairs of two electrons), excitons (bound states of an electron and a hole), and phonons. These collective phenomena exhibit peculiar properties under quantum mechanical conditions, such as superconductors where electrical resistance completely disappears at low temperatures, superfluids where liquid viscosity vanishes, and the properties of graphene. Scientists believed that quasiparticles could not exist in the macroscopic world because constituent particles like electrons constantly collide. Therefore, until now, quasiparticles were concepts observed or utilized only in quantum physics.

However, the research team experimentally and theoretically discovered a surprising phenomenon where particles form pairs and move together in materials visible to the naked eye. They focused on a particle system composed of colloidal particles in an ultra-thin microfluidic channel (liquid flowing between two thin plates). They found that in a two-dimensional particle system where the channel thickness is similar to the particle size, particles moving more slowly than the liquid influence nearby particles, causing them to pair up. This is because one particle experiences hydrodynamic forces caused by the movement of another particle, similar to how we can feel the flow of water caused by a person passing nearby even with our eyes closed underwater.

Research Fellow Park explained, "The reason particles form pairs is that the hydrodynamic forces between two particles break Newton's Third Law (the law of action and reaction: the two interacting forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction). The hydrodynamic forces acting on the two particles are equal in magnitude and direction, so they move as a pair like a single particle."

The research team also experimentally confirmed the existence of hydrodynamic phonons in addition to the phenomenon of particles moving in pairs. When atoms constituting a solid vibrate due to heat, a quantized quasiparticle called a 'phonon' propagates thermal energy throughout the crystal. Similarly, hydrodynamic forces cause particles in a regularly arranged macroscopic crystal to vibrate, generating hydrodynamic phonons. Analysis of phonons generated by hydrodynamic forces revealed a specific energy band structure previously observed only in graphene.

The team also discovered flat bands, previously observed only in quantum materials, in particle crystals visible to the naked eye. When two layers of graphene, carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal honeycomb two-dimensional crystal structure, are stacked at a specific angle, superconductivity without resistance occurs due to flat bands. The research team confirmed that quasiparticles and flat band phenomena appear when the visible particle crystal structure is made hexagonal. This is the first case where important phenomena of quantum materials, such as quasiparticles and flat bands, help in understanding the macroscopic world.

Research Fellow Park said, "This research result suggests that various phenomena explained only by quantum mechanics can occur not only in solids but also in living matter. We hope to discover quasiparticles in other visible materials and develop new science and technology based on them."

The research results were published online on the 27th in Nature Physics (IF 19.684).

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag, Saying "I Hate Being Poor but Real"... The Grotesque Con of a "Human Knockoff" [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)