Repeated Stalking Murders Highlight Urgent Need for System Reform

Perceived Between Misdemeanor and Sexual Violence, Stronger Penalties Needed

Most Stalking Victims Aged 20-29, Over Half Are 'Known Persons'

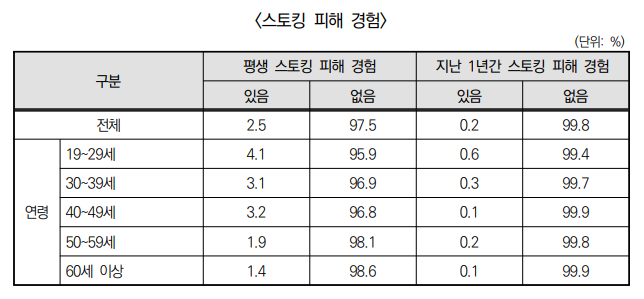

Strict 2.5% Stalking Victim Criteria, Limited Punishable Acts

Emergency Measures Up to 1 Month Insufficient to Prevent Recurrence

At the entrance of the women's restroom at Sindang Station on Seoul Subway Line 2, where a female attendant was killed by a coworker who had been stalking her, citizens continue to visit to pay their respects. Photo by Moon Honam munonam@

At the entrance of the women's restroom at Sindang Station on Seoul Subway Line 2, where a female attendant was killed by a coworker who had been stalking her, citizens continue to visit to pay their respects. Photo by Moon Honam munonam@

The stalking murder case of a female station attendant at Sindang Station has brought the effectiveness of stalking crime punishment and victim protection systems into question. Stalking is still perceived as a minor offense or somewhere between a minor crime and a sexual violence crime, leading to calls for harsher penalties and improvements in emergency and urgent protective measures for victims.

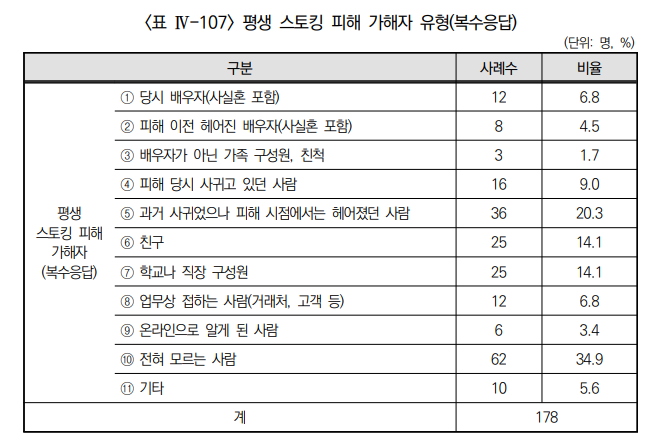

According to the 2021 Survey on Violence Against Women by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, among respondents who experienced stalking, 92.0% of perpetrators were male and 2.5% were female. The age group of victims at the time of stalking was highest among those aged 20-29 (65.1%), followed by 10-19 (11.2%) and 30-39 (10.7%). More than half of the women who experienced stalking were victimized by someone they knew, and among them, about 4 out of 10 victims were harmed by an intimate person.

The locations where stalking was experienced over a lifetime were offline spaces at 73.8%, online at 9.8%, and both at 16.4%, showing a relatively higher proportion of online occurrences compared to other types of violence against women. In the past year, the frequency of stalking experiences was highest at 2-4 times (42.9%), followed by once (38.8%) and 10 or more times (18.2%). Among 7,000 adult women surveyed, 16.1% experienced physical, sexual, emotional, or economic violence, while the stalking victimization rate was relatively low at 2.5%. This is due to the limited scope of stalking application, the short period since the law’s enactment, and insufficient coverage of the types of harm victims experience.

In the Stalking Punishment Act, stalking behavior is defined by the conditions that △ it is against the other party’s will △ there is no justifiable reason △ it causes anxiety or fear to the other party, and all these elements must be met. Attempts to strengthen punishment provisions to treat stalking as a more serious crime based on the nature and severity of stalking have ironically made the requirements stricter, limiting the acts subject to punishment. In particular, the phrase “anxiety or fear” as an emotional state required for the crime’s establishment has been criticized as inappropriate. Since many perpetrators are intimate persons, the provision allowing withdrawal of charges by the victim (non-prosecution upon victim’s request) urgently needs to be abolished. Considering victims’ fear of retaliation or their prior relationship with the perpetrator, asking for the victim’s consent can itself be a burden.

The aggravated punishment provisions for stalking crimes are also insufficient. Based on recent cases where stalking often leads to assault or murder, there are calls to establish consequential aggravated punishment provisions. Especially when stalking is prolonged and repeated multiple times, when an adult stalks a child or adolescent, or when the perpetrator is someone in a trusted relationship, these cases should be subject to aggravated punishment discussions. The German Penal Code punishes such cases with imprisonment from one year to ten years.

At the entrance of the women's restroom at Sindang Station on Seoul Subway Line 2, where a female attendant was killed by a coworker who had been stalking her, citizens continue to visit to pay their respects. Photo by Mun Ho-nam munonam@

At the entrance of the women's restroom at Sindang Station on Seoul Subway Line 2, where a female attendant was killed by a coworker who had been stalking her, citizens continue to visit to pay their respects. Photo by Mun Ho-nam munonam@

The victim protection measures under the Stalking Punishment Act last only up to 1-2 months, which is insufficient to protect victims. Emergency measures prohibit the perpetrator from approaching within 100 meters of the victim or their residence if there is a risk of stalking recurrence, but this cannot exceed one month. The court’s “provisional measures” allow prohibiting approach within 100 meters or blocking electronic communication for up to two months (extendable twice for two months each). However, provisional measures lose their effect if a non-prosecution or dismissal decision is made before investigation or trial is complete, even though the risk of re-approach remains high.

Researcher Jang pointed out, “Considering the psychological characteristics of perpetrators, stalking often repeats and continues, but emergency or approach prohibition measures do not cover repeated stalking. The requirement that police must judge there is a risk of continuous and repeated harm also needs improvement. Even if the 1366 Center and police are linked, it is difficult to collect evidence for stalking without visible harm.”

Improving public awareness of stalking crimes is also urgent. Seoul City Council member Lee Sang-hoon’s comment on the Sindang Station case, saying “He reacted violently because his feelings were not reciprocated,” is a representative example. Researcher Jang criticized this, saying, “Causing fear and coercion is a form of violence, and dismissing it as an emotional issue of the perpetrator is an outdated view. People must recognize that causing fear is a crime.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

!["The Woman Who Threw Herself into the Water Clutching a Stolen Dior Bag"...A Grotesque Success Story That Shakes the Korean Psyche [Slate]](https://cwcontent.asiae.co.kr/asiaresize/183/2026021902243444107_1771435474.jpg)