Hankyung Research Institute Analyzes OECD and Statistics Korea Data

Comparison of Top 4: Denmark, Norway, Germany, and Netherlands

Commuters are hurrying on the streets near Gwanghwamun, Seoul, on their way to work. Photo by Hyunmin Kim kimhyun81@

Commuters are hurrying on the streets near Gwanghwamun, Seoul, on their way to work. Photo by Hyunmin Kim kimhyun81@

[Asia Economy Reporter Kim Heung-soon] It has been argued that South Korea lacks labor productivity and labor flexibility compared to countries where people work less but earn more, such as Denmark, Norway, Germany, and the Netherlands. The point is that human capabilities need to be strengthened so that more people can work efficiently.

According to an analysis by the Korea Economic Research Institute (KERI) under the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI) of OECD statistics and data from Statistics Korea ahead of Labor Day (May 1), the annual average working hours in Denmark, Norway, Germany, and the Netherlands?countries with the shortest working hours?were 1,396 hours, and the per capita gross national income was $60,187. South Korea works 1.4 times more than these countries but its income level is half ($32,115).

KERI identified five major characteristics of these countries: ▲high employment rate ▲high labor productivity ▲high labor flexibility ▲activation of part-time work ▲high level of human resources.

South Korea Ranks Low in OECD for Labor Productivity and Labor Flexibility

The average employment rate of the four comparator countries was 76.4%, which is 9.6 percentage points higher than South Korea’s 66.8%. The gap with the Netherlands was 11.4 percentage points. KERI explained, "To achieve the Netherlands’ employment rate level, about 4.186 million more jobs need to be created in South Korea." The gap in female employment rate with the Netherlands was even larger at 16.3 percentage points.

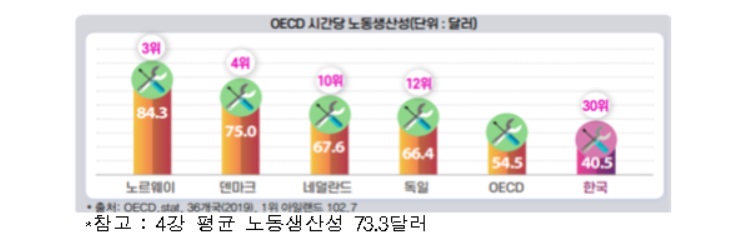

Hourly labor productivity in Norway was $84.3, more than twice that of South Korea’s $40.5. South Korea’s labor productivity ranked 30th out of 36 OECD countries, placing it in the lower tier, and its ranking dropped by one place compared to the previous year.

In the World Economic Forum (WEF) labor market flexibility evaluation, which comprehensively assesses labor market competitiveness, South Korea scored 54.1 points, ranking 35th out of 37 OECD countries, whereas the average score of the four leading countries was 68.9 points. Denmark, with the highest score of 71.4 points, ranked 3rd among OECD countries and 4th among 141 countries evaluated. These countries had a high proportion of part-time work; for example, the Netherlands’ part-time work rate was 37.0%, 2.6 times higher than South Korea’s 14.0%. The WEF human resources skills score averaged 84.6 points, ahead of South Korea’s 74.0 points.

There were also differences in how finances were used to support jobs. South Korea’s direct job creation budget was about 0.15% of GDP, significantly higher than the four leading countries. In contrast, the vocational training budget was low at 0.03%. Denmark, for example, had almost no direct job creation budget but spent 0.39% of GDP on vocational training, the second highest among OECD countries.

Long-term Reforms Based on Labor-Management Agreements

Need to Secure Labor Flexibility and Improve Labor Productivity

KERI pointed out that the decisive factor enabling these countries to work less and earn more was securing labor flexibility through labor market reforms. The Netherlands, through the Wassenaar Agreement (1982), saw labor voluntarily restrain wage increases and promoted reduced working hours and part-time employment under 30 hours. As part-time work became more active, the female employment rate rose significantly from 35.5% in 1985 to 62.7% in 2000. Additionally, reforms in social security systems were achieved, including reducing public sector employment, freezing civil servant salaries, and lowering taxes.

Germany faced rising unemployment and increased social welfare burdens after reunification in 1990, prompting the need for labor reforms. Through the Hartz reforms (2003), Germany sought to create flexible jobs such as "minijobs" and "midijobs." Regulations under the Worker Dispatch Act were abolished (removal of dispatch period limits and repeated re-employment bans), and dismissal restrictions were relaxed (from companies with 5 or more employees to those with 10 or more), enhancing labor market flexibility. As a result, the unemployment rate dropped from 11.3% in 2005 to 4.7% in 2015. Youth unemployment also fell from 15.2% to 7.2%.

Denmark and Norway have also pursued long-term reforms based on mutual trust between labor and management. Denmark’s September Agreement (1899) and Norway’s tripartite basic agreement (1935) are considered cultures of agreement that set procedures to follow in labor disputes. Denmark implemented employment promotion programs for the unemployed and improved the quality of vocational training through the third labor market reform (1998). Germany shortened the maximum unemployment benefit period from 32 months to 18 months and imposed active job-seeking obligations through the Hartz reforms.

Choo Kwang-ho, head of economic policy at KERI, emphasized, "Countries that work less and earn more are characterized by higher employment rates through activation of part-time work and deregulation of labor, and high income levels based on high productivity. South Korea can become a job-advanced country if it enhances human capabilities through vocational education rather than direct job creation and improves labor flexibility through labor-management agreements."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.