First Default Nine Years After Independence in 1827... Eight Defaults So Far

Rapid Decline from Top 10 Global Economies

Alternating Failures of Populism and Neoliberal Reforms

Peronist Populism with Nationalization of Key Industries and Welfare Expansion

Neoliberal Reforms Also Fail to Deliver Results

Attention on Debt Restructuring Amid COVID-19 Situation

[Asia Economy Reporter Naju-seok] Argentina's ninth default is entering the final countdown. If no agreement is reached with creditors in the debt restructuring negotiations extended until the 22nd for the $65 billion (80.14 trillion KRW) debt, Argentina will be nominally bankrupt. The country's finances are so depleted that it must pay $500 million in interest by the negotiation deadline.

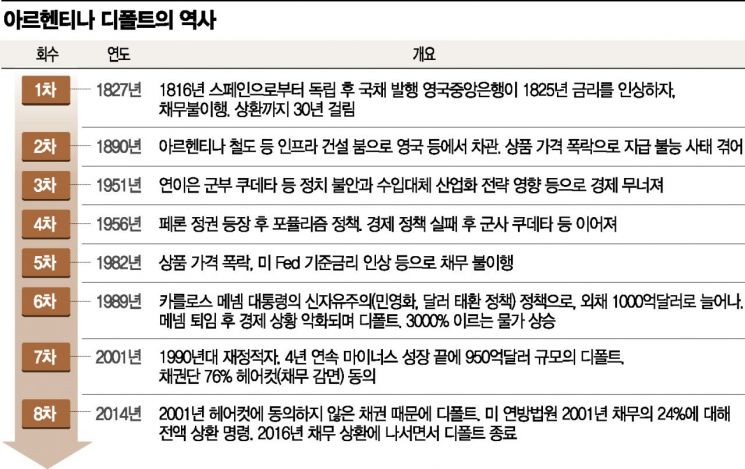

It is no exaggeration to say that Argentina's history is a history of defaults. Since its independence in 1816, it has declared default eight times. The first default was declared in 1827. After independence, Argentina issued government bonds in London's financial market to raise massive national funds, but when the Bank of England raised interest rates in 1825, Argentina declared default. Argentina was able to repay its debts and re-enter the international financial market 30 years later. Subsequent defaults occurred in 1890, 1951, 1956, 1982, 1989, 2001, and 2014.

In the 19th century, Argentina was one of the agricultural powerhouses. Until before World War I, it was among the top ten advanced countries in the world by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This was thanks to wealth generated through livestock and agriculture utilizing the Pampas plains.

However, when President Juan Domingo Per?n took office in 1946, the national wealth accumulated until then began to collapse rapidly. Peronism, which advocated wealth redistribution, nationalized key industries, and strengthened welfare, worsened the economic situation. Fiscal soundness was neglected.

Benjamin Gedan, director at the Wilson Center and an Argentina expert, pointed out, "The main reason Argentina declares default is because fiscal rules are not followed. They needed dollars for revenue and borrowed dollars for this, but operating a closed economy made it impossible to repay the borrowed money. This has happened repeatedly."

Defaults in Argentina have become more frequent since the 1980s. Four of the eight defaults occurred within the last 40 years. It is especially noted that the alternating rule between Peronism and its opposite, neoliberal regimes, further complicated the economic situation. Many attribute the current ninth default situation to the failure of reforms by former President Mauricio Macri, who advocated market-oriented reforms. Macri implemented policies to cut various subsidies to reform Argentina's reckless fiscal situation. He also pursued repayment of debts left unpaid during the 7th and 8th defaults to attract foreign capital, adopting pro-market policies. While foreign investment increased and the economy showed signs of recovery, the situation reversed as the peso's value plummeted. The weak peso exchange rate increased Argentina's external debt burden.

The market views Argentina as suffering from chronic moral hazard. Although the COVID-19 pandemic also had an impact, frequent defaults have led Argentina to take debt relief for granted. Argentina has proposed to creditors a three-year repayment deferral, a 62% interest cut, and a 5.4% principal reduction. Argentina shows no intention of revising this proposal and rather demands creditors decide whether to accept it.

There are also criticisms that Argentina is deliberately trying to reduce its repayment capacity. The Argentine government projects the 2030 GDP at $558 billion (687.3 trillion KRW) when explaining its debt repayment ability. This is $120 billion less than the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimate. This is the opposite of the usual situation where countries inflate economic forecasts compared to international organizations. It is said that the Argentine government is trying to lower economic growth forecasts to reduce its debt burden.

A creditor representative said in an interview with foreign media, "Argentina likes to say it will do everything possible, but compared to other countries, it does not. There is no structural effort to operate a restrained fiscal policy in the medium term."

Additionally, there are calls for Argentina to actively pursue banking reform. Having experienced the peso's depreciation during crises, Argentinians tend to convert their peso deposits into dollars in overseas accounts rather than deposit in domestic banks. At least $300 billion in deposits are saved in overseas accounts, but this capital rarely flows back into Argentina.

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.