55% of Savings Banks Do Not Exceed 20% Overloan Limit

Small Businesses Face Suspension of Low-Credit Loans

Warnings of Vulnerable Groups Turning to Illegal Private Loans

[Asia Economy Reporter Song Seung-seop] The savings bank industry is rapidly reducing the proportion of high-interest loans exceeding 20% per annum ahead of the statutory maximum interest rate reduction scheduled for July. Unlike large savings banks that have adjusted their interest rates, some small-scale firms have stopped lending to low-credit borrowers, raising concerns that a 'loan cliff' may be becoming a reality.

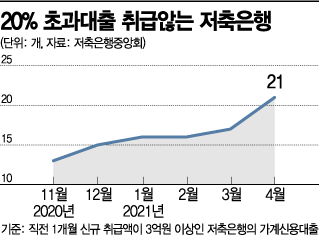

According to the Korea Federation of Savings Banks on the 22nd, out of 38 savings banks handling household credit loans, 21 were found not to offer loans exceeding 20%. This is an increase of four from last month, surpassing half (55.26%) of the total. Considering that only 10 banks refrained from high-interest loans when the government and the Democratic Party finalized the maximum interest rate reduction plan last November, the move to reduce high-interest loans appears to be accelerating.

The statutory maximum interest rate of 20% was a campaign pledge by President Moon Jae-in and was previously lowered once from 27.9% to 24% in February 2018. In September last year, the Financial Services Commission was instructed to review the market impact of the interest rate reduction. Subsequently, with amendments to the Loan Business Act and the Interest Limitation Act Enforcement Decree, the government announced that the maximum interest rate would be lowered to 20% starting July 7.

In response, JT Savings Bank was the first in the industry to adjust interest rates exceeding 20% per annum, reducing their proportion to 0%. This move is seen as a proactive risk adjustment in response to the maximum interest rate reduction without halting loans to creditworthy borrowers.

Savings banks that still maintain loans exceeding 20% are gradually lowering their proportions. A representative from a large savings bank explained, "Large firms continue to provide loans to as many low-credit borrowers as possible, which is why loans exceeding 20% still exist," adding, "We are adjusting interest rates gradually and plan to retroactively apply the interest rate reduction to most borrowers once the maximum interest rate reduction is implemented."

The problem lies with some small and medium-sized savings banks that have begun to stop new loans to low-credit borrowers. For example, a savings bank located in Jeonbuk lent money even to borrowers with a credit rating of 10 in November. However, by April, loans were only extended to borrowers with a rating of 9 (credit score between 445 and 514). Similarly, a savings bank in Incheon previously allowed loans up to an 8 rating, but from this month, borrowers must have a credit score between 601 and 700 to qualify for a loan.

Small Savings Banks Say "It's Difficult to Endure Maximum Interest Rate Reduction"... Is the 'Loan Cliff' Approaching?

Unlike large savings banks, small firms explain that they find it difficult to withstand the profit decline caused by the interest rate reduction. It is interpreted that they are not lowering loan interest rates for low-credit borrowers but are instead ceasing to handle new loans altogether. Another savings bank official analyzed, "Small savings banks are already in a deteriorated management situation," adding, "The decision was likely unavoidable due to the impact of the interest rate reduction."

Industry and academia have long expressed concerns that if interest rates fall to 20%, vulnerable groups might turn to illegal private loans.

According to recent research by the Korea Inclusive Finance Agency, "Since the maximum interest rate reduction in 2018, the number of vulnerable groups receiving high-interest loans from illegal private lenders has increased," warning that "over time after the maximum interest rate reduction, the loan business has continuously shrunk due to the profitability of lending businesses and the worsening credit of users." This criticism highlights that the use of illegal private loans by vulnerable groups remains, and the lending industry has contracted.

The Credit Finance Research Institute also pointed out in a report at the end of last year that "When Japan lowered its maximum interest rate, the lending industry shrank, and the number of illegal loan users increased sevenfold." In June 2010, Japan reduced the maximum interest rate under the Investment Law from 29.2% to 20%. The supply of funds did not meet loan demand, and an increase in illegal lending was observed as a side effect.

In response, Financial Services Commission Chairman Eun Sung-soo met with reporters directly and said, "We will prepare measures through policy," but criticism has already emerged on the ground that the loan cliff has begun.

Professor Sung Tae-yoon of Yonsei University's Department of Economics remarked, "While limiting the maximum interest rate seems good, it may push borrowers toward illegal private loans," adding, "Although it may have started with good intentions, it was a policy with anticipated side effects." He further criticized, "If the goal was to reduce the interest burden, it should have been addressed through policy support rather than financial intervention."

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.