![[Economic Insight]Splitting the Ministry of Economy and Finance? Why Is It Necessary?](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimglink/1/2024052714233685591_1716787416.jpg)

The Lee Jaemyung administration signaled plans for government restructuring from the presidential campaign, including splitting the Ministry of Economy and Finance and establishing a new Ministry of Climate and Energy. Although these reforms appear to have taken a back seat due to the priority given to immediate economic issues, the government seems firm in its intention to push forward with them.

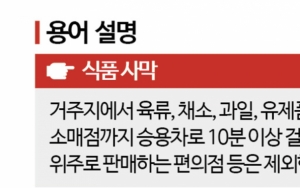

Economic policy is broadly divided into macroeconomic and microeconomic policies. Macroeconomic policy consists of fiscal policy (budget and taxation) and monetary policy (base interest rate), while microeconomic policy includes various detailed measures, with financial policy being the most significant. At the top is overall economic coordination, that is, economic planning (strategy) and inter-ministerial policy coordination.

In the past, the Economic Planning Board / Ministry of Finance (up to the Roh Tae-woo administration) handled overall economic coordination, budget, taxation, and finance. During the Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun administrations, the Planning and Budget Commission / Ministry of Finance and Economy divided responsibilities into budget, overall economic coordination, taxation, and finance. Since the Lee Myung-bak administration, the current Ministry of Economy and Finance / Financial Services Commission has separated powers into overall economic coordination, budget, taxation, and finance.

However, under the Ministry of Finance and Economy (during the Kim Young-sam administration), all major economic policy areas?overall economic coordination, budget, taxation, and finance?were concentrated in a single “super ministry.” Before the independence of the Bank of Korea was secured by the amendment of the Bank of Korea Act in December 1997, this ministry also exerted strong influence over monetary policy, effectively holding all economic powers. As a result, unlike when powers were separated, checks and balances did not function properly, which led to criticism that this contributed to the 1997 foreign exchange crisis.

The current discussion about splitting the Ministry of Economy and Finance can be traced back to the dismantling of the Ministry of Finance and Economy. The rationale for splitting the ministry is based on the fundamental principle of checks and balances. When powers are distributed among ministries, they can voice differing opinions and even clash over certain issues, which leads to more desirable decision-making?this is the principle of checks and balances.

A representative example is the securing of the Bank of Korea’s independence. In the past, the Bank of Korea was nicknamed the Namdaemun branch of the Ministry of Finance (including the Ministry of Finance and Economy). The chair of the Monetary Policy Committee, which determines monetary policy, was the Minister of Finance. Since 1998, with the Bank of Korea’s independence, the Governor of the Bank of Korea has chaired the committee.

Kang Mansoo, the first Minister of Economy and Finance under the Lee Myung-bak administration, advocated for a high exchange rate policy (depreciation of the won) to boost export competitiveness and insisted on lowering interest rates or at least not raising them to stimulate the economy. This led to frequent conflicts with Lee Seongtae, the Governor of the Bank of Korea. A high exchange rate raises import prices and pushes up consumer prices, but since price stability is the Bank of Korea’s top priority, it could not simply follow the ministry’s wishes. While the final authority over exchange rates (foreign exchange policy) rested with the ministry, the base interest rate was independently set by the Bank of Korea.

Conversely, immediately after the 1997 foreign exchange crisis, an excessively high interest rate policy became a problem. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed high interest rates to promote corporate restructuring (such as debt reduction) and to secure foreign exchange liquidity. At that time, the Ministry of Finance and Economy argued strongly to the IMF that normalizing interest rates was necessary, as otherwise even healthy companies would collapse. However, the Bank of Korea, which considered the IMF’s policy appropriate, was initially lukewarm. After intense negotiations, Korea renegotiated with the IMF, and the agreement led to a drop in the market interest rate (91-day negotiable certificates of deposit) from 24% per annum in January 1998 to about 10% in September of the same year. As a result, a wave of corporate bankruptcies was averted.

The “mega bank” plan (merging Korea Development Bank, Industrial Bank of Korea, and Woori Bank), which Minister Kang Mansoo actively pursued in the early Lee Myung-bak administration to foster global banks, was ultimately blocked by the Financial Services Commission due to concerns about undermining the autonomy of private finance and the potential side effects of creating a large state-owned bank.

Now, it is unclear what kind of “checks and balances” effect is being sought by removing the budget function from the Ministry of Economy and Finance. Is it because the ministry does not grant the National Assembly’s requests for budget increases? Is it to allow the presidential office or the prime minister’s office to control the budget at will? If so, isn’t the ministry effectively providing a check on the National Assembly and the administration?

Or is it because the ministry is too rigid and arrogant? While I am well aware of how other ministries view the Ministry of Economy and Finance, this alone seems insufficient as a rationale for splitting the ministry.

The plan to create a Ministry of Climate and Energy by merging the energy division of the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy with the Ministry of Environment also disregards the principle of checks and balances. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy is responsible for designing the nation’s energy strategy and ensuring energy supply, while the Ministry of Environment is focused on regulating fossil fuels for environmental protection. If these are merged, only one voice will prevail, regardless of which side it is.

It is time to recall once again the fundamental principle of “checks and balances.”

Finally, I will close with the words of a former high-ranking official from the Ministry of Economy and Finance whom I recently met.

“As a lesson from the era of the Ministry of Finance and Economy, it has become clear that budget, taxation, and finance cannot all be housed in a single ministry. The question is which function should be separated. Each administration has its own philosophy and direction, and reform is justified if there are problems with the current system. However, it must be clearly recognized that such reform comes with costs.

The costs of splitting a ministry are not limited to the need for additional personnel in common departments such as human resources, general affairs, parliamentary affairs, and public relations. There are also invisible costs. From the lowest to the highest levels (section chief, director, bureau chief, vice minister, minister), there are established inter-ministerial working relationships and ways of doing things. If a ministry is split, these working relationships and methods must be completely rebuilt. The time and costs involved in this process are by no means trivial.”

© The Asia Business Daily(www.asiae.co.kr). All rights reserved.

![[Economic Insight]Splitting the Ministry of Economy and Finance? Why Is It Necessary?](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimglink/1/2025061307500096599_1749768600.jpg)